The natural use the word ‘judgement’ is to denote a mental act of attributing a predicate to a subject. In that sense, the act of judging primarily involves inference, that is, determination of the connotation of the subject, or attribution of certain property to the object even if the inference arrived at, or the attribution cast upon, are not justified or derived through argumentation.

This conception, rooted in the classical tradition extending from Aristotelian logic through contemporary analytic philosophy, generally understands judgement as the attribution of properties to particular objects or subjects.

In the legal context, where a judge is required to deliver a judgement based on facts and to justify the inference or attribution, this conception reflects as the determination that particular factual or normative claims are true or false. This determination carries significant practical consequences.

When a court determines that a person is guilty of negligence, it is making a substantive assessment about the relationship between ‘individual agency’ and the legal consequence of the use of the agency. The underlying conclusion is the result of determinations about personal identity over time, the nature of causal responsibility, and the ontological status of legal properties. In this case, the court has passed a judgement that a person is guilty of a particular offense, and it differs from a more generalised judgement that “negligence must be punished with liability”.

However, some judgements do not involve such attributions or objects. This dimension concerns their relationship with truth—as a determination, recognition or attribution of truth values to factual or normative claims.

Take the Kesavananda Bharati (1973) judgement, which arguably represents the most important example of such truth value attribution in Indian constitutional law. The Supreme Court held that parliament’s power to amend the Constitution was subject to implicit limitations that preserve the Constitution’s basic structure. Here, the alethic dimension manifested through the court recognising the truth of a constitutional interpretation that curbed parliament’s powers.

The language of judicial judgements is the language of logic. These conceptions reveal that judicial judgements, much like other judgements, emerge not just as a derivative phenomenon but as the fundamental structure within which cognitive activity occurs. Institutions ensure that questions about the characterisation of persons and events are addressed through processes that take seriously both epistemic concerns about truth and concerns about fair procedure.

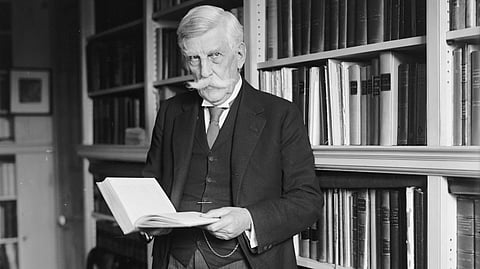

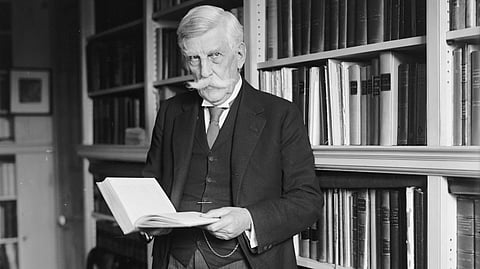

However, as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr of the US Supreme Court once noted, “The whole outline of the law is the resultant of a conflict at every point between logic and good sense.” In Common Law (1881), Justice Holmes elaborated: “The actual life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience. The felt necessities of the times, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than syllogism.”

As legal realists would attest, judges’ background, beliefs, temperament and even the demeanor of the arguing counsels affect the manner in which issues are framed and weighed. This, however, is not because the judges are acting in bad faith or pursuing an agenda. Rather, their lived experiences, which is what Justice Holmes refers to as “good sense”, lead them to see the same legal issues differently, even if the language of their judgements follow the same logic. For example, one cannot deny that Kesavananda Bharati was a product of its time.

How does one then criticise judgements, especially ones that deal with constitutional issues? One way would be evaluating the judgements based on their fidelity to formal logic and its methods. Yet, this may not always capture the undercurrents driving legal developments.

Another way would be adopting pragmatism, to judge judgements on the basis of their practical outcomes. There always being a competing “good sense”, as long as the outcomes are not anathematic, the judgement must stand. Finally, we may judge also on the basis of whether the judge has adequately acknowledged and tested their pre-suppositions in the form of adherence to procedure.

Take the recent interim order of the Madras High Court staying an amendment taking away the governor’s power to appoint vice chancellors. The criticism of the order primarily focused on what some labelled as ‘misplaced urgency’, pendency of a transfer petition before the Supreme Court, and an alleged lack of opportunity to file a counter.

However, the criticism ignores the fact that Tamil Nadu had already constituted search committees, issued government orders, published advertisements, and commenced the selection process for vice-chancellor appointments. The criticism fundamentally misunderstands judicial duty. The SC had given no stay order or oral injunction, preventing the high court from proceeding. All of these, including the issue of opportunity to file counters, are dealt with in the order.

It is not that the high court’s order is immune to critique. The inadequacy of the criticism simply points to a broader problem: we tend to criticise constitutional judgements through result-oriented attacks or procedural nitpicking. A better approach would be to engage with alternative constitutional interpretations and their practical consequences, while maintaining transparency about our own motivations, values and assumptions.

Saai Sudharsan Sathiyamoorthy | Advocate, Madras High Court

(Views are personal)

(saaisudharsans@gmail.com)