How to evaluate the omissions of the Finance Commission

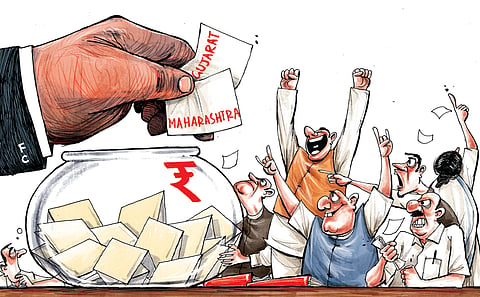

The sharing of the divisible pool of taxes between the Union government and states is a zero-sum game—if the Union gets even a bit more, the states would get that much less; within the states’ share, if one gets more, others would get less. Hence the formula for the sharing or devolution is extremely consequential.

Every five years, the Union Finance Commission (FC), a constitutionally mandated body, decides how this pool, which includes the income tax we pay, is divided. The 16th FC, whose report was tabled in Parliament along with the Union Budget, has decided that for the period 2026-31, the states will get 41 percent—the same as what the 15th FC recommended and slightly lower than the 14th FC’s 42 percent, which had raised the states’ share substantially from 32 percent.

The question is how this 41 percent will be distributed between the states. Given the contentious stakes, every state advocates its own formula for determination of the share. Let’s see who the latest Union FC’s formula helps more.

One important criterion used by successive FCs to arrive at the states’ individual shares is income distance. This ensures that the richer states get smaller shares of the pie. Understandably, the states that had a higher per-capita income were of the view that, as engines of growth for the Indian economy, they deserve a larger portion.

The 16th FC reduced the weight given to the income distance from 45 percent awarded by the 15th FC to 42.5 percent. It also reduced the weight given to the area of the state from 15 percent to 10 percent, but increased the weight given to the population from 15 percent to 17.5 percent. Other than the increase in the population weight, the other two changes would work in favour of most southern states (except Karnataka), since they are smaller.

A higher weight to population benefits the likes of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Maharashtra, whereas a lower weight to area does not help Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. For Maharashtra, as long as the population and area are given an adequate weight, it works in its favour. The combined weight for population and area was 30 percent in the index developed by 15th FC, while it’s given 27.5 percent by the 16th FC.

Forest cover was given a weight of 10 percent by both the 15th and 16th FCs. Apart from the adjustments, the 16th FC should be commended for introducing a new criterion—contribution to the national GDP, with a weight of 10 percent—that nine states had argued for. This should have worked to the benefit of all the richer states, but even then it was not enough to get all of them back to their earlier shares based on the 14th FC’s criteria.

In order to understand the winners and losers, it is best to examine the inter se shares of the states based on the formula used by 14th, 15th and 16th FCs. The states whose shares have increased steadily are Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Punjab, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Mizoram. And because of how the indicators were chosen and the weights assigned, the biggest gainers in this lot are Maharashtra and Gujarat. The two states whose shares declined across the last three FCs are Odisha and Uttar Pradesh. While the share of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Telangana increased between the 15th and 16th FCs, their shares this time are lower than what they got from the 14th FC. The state that gained just a little between the 14th and 16th FC was Tamil Nadu—from 4.023 in the 14th, to 4.079 in the 15th, and 4.097 percent in the latest.

The commission’s decision to include contribution to India’s GDP as a criterion did not benefit the richer states, in particular the southern ones, to the extent it should have. This is because of the way the contribution was calculated. Suppose there are only four states and their contributions to the GDP are, say, ₹100, ₹81, ₹64 and ₹49. This means that their shares would be 34, 27, 22 and 17 percent, respectively.

But what the commission did was to calculate the shares based on the square root of their contributions—at ₹10, ₹9, ₹8 and ₹7 in our example. This means that the states’ shares are 29, 26, 24 and 21 percent. Notice how the share of the top contributor declines while that of the lowest rank state rises. This is acknowledged by the commission in its report. The case of the southern states and the minuscule increase especially for Tamil Nadu would have been discussed at the FC’s deliberations.

Given that contribution to GDP is now a criterion, it’s important that we estimate the gross state domestic product (GSDP) of each state accurately. Now, it’s well known in the policy circles that the departments of economics and statistics across states have limited capacity—it’s the Achilles’ heel of the states’ statistical edifice. All eyes are trained on the forthcoming release of the revised GDP numbers after the revision of the base year. A similar attention needs to be paid to the GSDP series of the states.

The Committee for Sub-National Accounts chaired by Ravindra Dholakia, which submitted its report in March 2020, had specific recommendations for strengthening the state economics and statistics departments so that a bottom-up approach could be followed for calculating GDP—from state aggregates to the national aggregate.

One constraint each FC faces is that the indicators it chooses need to be available for all states and be acceptable to all states. On most verifiable indicators, for all states, Maharashtra and Gujarat are generally not at a disadvantage. The proof is in the pudding. Maharashtra’s share increased from 5.521 percent in the 14th FC to 6.441 in the 16th, while that of Gujarat increased from 3.084 percent to 3.755 percent.

With a nod to generations of work on state statistics and with the tongue firmly in cheek, it can be said that while ‘lady luck’ smiles on Maharashtra and Gujarat given the combination of their size and the devolution formula, the southern states continue to face ‘dumb luck’. In a way, that’s an apt summary of this zero-sum game of immense significance that plays out every five years.

S Chandrasekhar | Professor at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research and member of the Steering Committee for National Sample Surveys

(Views are personal)

With inputs from Anushka Nagar, research scholar at IGIDR