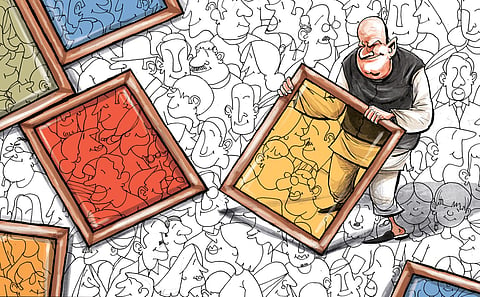

Nearly a hundred years after Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar’s famous treatise, The Annihilation of Caste, who would have thought that India would turn a full circle, or should I say turn turtle? For today, Indian society, by and large, wants to leave caste behind. It wants to move on. But it cannot. Because the government of the day will not let it.

Yes, ordinary Indians cannot ever forget or move beyond their caste. The Indian State and the political classes that run it will never let us. It is they who have reinforced, again and again, how casteist we are.

As Neha Das, a self-proclaimed general caste rights activist, posted on her X account: “Beauty of Reservation Republic of India: If you demand caste-based reservation, caste-based fees, caste-based hostels, caste-based scholarships, caste-based A to Z things, you are called ‘anti-caste’! And if you oppose such caste-based policies, you are called ‘casteist’!”

In other words, today, those who want the annihilation of caste are casteist, while those who want everything on the basis of caste are anti-caste.

Here’s another bon mot from X: “Free coaching / SC ST OBC higher age limit / SC ST OBC cheapest forms / SC ST OBC reservation in results / SC ST OBC departmental promotions. Govt signs MoU with PhysicsWallah for free coaching to SC, ST, OBCs. For the general category, there is no quota, no scheme, no policy, no help from the government—only tax.” (sic)

The recent protests over the University Grants Commission’s equity regulations underscore the point. Its draft as late as February 2025 did not include OBCs in the “oppressed” group of students. How and why were they inserted into the regulations? This is worth examining separately. But it is surely fascinating, sociologically and politically, how the traditional varna system of India has thus been upended, even superseded, by the new governmental caste system.

Remember the furore over the economically weaker sections (EWS) category? Introduced through the 103rd Constitutional Amendment Act in 2019, it raised the hackles of several caste crusaders, because for the first time economic—and not merely social—criteria were recognised as markers of backwardness.

So, what do we have by way of the State varna system? SC/ST, OBC, EWS and of course, by default, GC. The last, general category, includes all those left out from the deprived classification. A new four-fold government-sanctioned and enforced caste quota system, which many would deem even more iron-clad and oppressive than the one it supersedes.

But sitting above all of them is the super-caste of PCs—permanent category government servants, those who cannot be fired. Among these too, as in the traditional caste system, are multiple gradations and hierarchies. Those in the coveted—and much maligned—Indian Administrative Service are, evidently, on the top. You can’t get any higher, at least on Earth. Naturally, all the others, SC, ST, OBC and GCs, want to crash into the ranks of the PCs.

That, in a line, is what the struggle over upward mobility is all about.

If we include women as a deprived section of society by virtue of their sex, we have a category by itself, superadded and overlapping with all of the above. In Jawaharlal Nehru University, where I taught for 25 years, female students receive 5 percent deprivation points. In ‘feminine gender’ subjects like English, where most students are girls in the first place, the extra 5 percent deprivation points ensure that very few boys make it. As a former chair of the Centre for English Studies, when I suggested half-jocularly that in English it is boys who should get deprivation points, the JNU administration wasn’t amused.

But if females are also included among the oppressed, the GC oppressors would be an even smaller section of society, continually demonised as Brahmins have been. This would suit the identity-politicswallas. A small section of society can serve as the perpetual scapegoat for their greed and ambition.

Let us return to the really backward or truly deprived among the GCs. During Mandal 1.0, some of them immolated themselves. Now, in the Kamandal phase, these unfortunates are once again reacting with frustrated anger and impotent outrage.

But it is hard for GC identity politics to push back against reverse discrimination. Partly because the smartest and most privileged of them GCs have already found the ways and means to escape the system. Whether by studying in private schools and colleges, or going abroad, or inheriting family businesses, property and wealth. They neither seek nor need anything from the government. They are already on their way out of the tentacles of government-sponsored casteism.

Amid demands for caste censuses and expanding reservations, Indian society yearns to transcend caste. Younger Indians, especially in the urban segments, increasingly reject caste. Inter-caste marriages have risen steadily, signalling a cultural shift toward individual rather than community identity. Moreover, several privileged OBCs already leave the caste column blank. Some SCs and STs are also following suit.

But this is India’s tragedy: we want to get out of caste, but cannot. Because the State and political classes perpetuate it through relentless interventions. This reinforcement not only revives caste in daily life but employs it as a tool to divide and rule, fostering resentment and social division.

The cure can only be found where the fault originates—in our government and political classes. To change this, we must hold the proverbial caste bull by its horns. We must return to the first principles of our Constitution. We must reform the quota system so that caste is no longer the sole or primary marker of deprivation. We must stop weaponising caste to fragment Indian society.

Perhaps we will need GC caucuses and anti-caste alliances across castes to spearhead a new political agitation in India against the new caste system created by the state and enforced by the government. I hazard to say that true constitutionalists, including Babasaheb Ambedkar, would approve.

Makarand R Paranjape | RIGHT IN THE MIDDLE | Author, educator and commentator

(Views are personal)

(Tweets @MakrandParanspe)