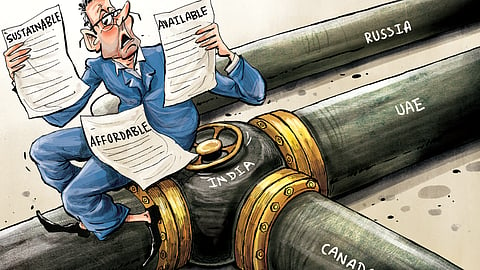

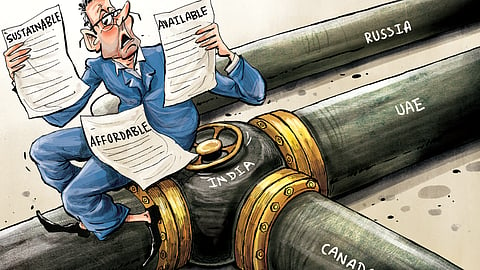

There is a new buzzword on India’s petroleum and gas landscape: trilemma. It is meant to convey the rationale behind actions by the government and fuel companies to balance energy availability, affordability and sustainability in the country.

India’s energy trilemma has been at the front and centre of policy decisions since US President Donald Trump demanded last year that India should stop buying cheap Russian oil. In August, Trump followed up this demand with Executive Order 14329 raising duties on Indian exports to the US to a whopping 50 percent. The punitive tariff caused pain when workers across India were laid off, factory floors turned idle and exporters ceded painstakingly-built markets in the US to global competitors.

Trump’s penal actions were the culmination of a process that was in the making since India switched to Russia as a major source of crude oil after Moscow offered huge discounts to fund its war in Ukraine. And for increased purchases of Russian defence equipment such as the S-400 missile system. Only, the Indian public was largely unaware of the resentment that was building up in Washington, caught up as they were in illusions of a special relationship between India and the US.

The energy trilemma was addressed when Petroleum and Natural Gas Minister Hardeep Singh Puri and External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar visited Mozambique within six months of each other a year after the Ukraine war began, triggering anxieties globally about another ‘oil shock’. Mozambique is a gas and coal producing country and an aspiring crude producer. Who would have imagined before this new threat to energy security that Puri and Jaishankar would be followed by a minister of state and a secretary for economic relations in the external affairs ministry to this otherwise neglected outpost? Or that red carpet would be rolled out by India for Mozambique’s defence minister, National Assembly speaker and secretary of state for trade?

In July 2025, Puri prised open the doors of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries cartel and addressed a meeting at the organisation’s headquarters in Vienna. There, he pursued expansion of energy ties with Nigeria and Kuwait in separate meetings with the former’s minister of state for petroleum resources and the latter’s oil minister, who is also chairman of Kuwait Petroleum Corporation, the national oil giant. The ground for adding Nigeria as a major source of crude and hydrocarbons trade had already been prepared by Puri and the Nigerian minister in Davos in 2024. Nigeria had been in a free fall on India’s trade ranking because oil purchases had come down by half before Puri’s initiatives in Davos and Vienna. To shore up these efforts, Jaishankar also visited Abuja in 2024.

Kuwaitis were pioneers among the Gulf Arabs to unveil vistas of energy cooperation with India. But frustrated in the past by India’s red tape and obstructionist bureaucracy, they had given up. Now, Kuwait’s rank on India’s energy charts has risen to the sixth place as a source of crude, fourth as a source of liquefied petroleum gas and eighth as India’s hydrocarbon trade partner. In the 1980s and 90s, India was a supplicant at Opec’s doors. Now it is on its way to becoming a partner, demanding respect as the world’s third largest importer of oil.

A series of initiatives such as these to address India’s energy trilemma gave Prime Minister Narendra Modi the confidence to declare on January 27, “India is now on a mission of energy independence, moving beyond energy security.” Modi’s government was hobbled in its first term by pump price mismanagement of petrol and diesel, and the pain inflicted on consumers of cooking gas and kerosene. A few achievements were reactive to offers by new friends of Modi among oil producers like the United Arab Emirates and Indonesia, rather than the result of proactive policies.

The Covid pandemic was a challenge as well as an opportunity. Uncertainties and fears of an all-round chaos prompted the government to heavily concentrate on the affordability factor in the trilemma. Aggressive cuts in central excise on petrol and diesel in 2021 and in 2022 were followed by reductions in value added tax by several states. Price charts provided to by petroleum marketing companies during the two post-Covid years show that diesel price rises in India were much smaller than the ones in the US, Canada, Spain and the UK.

Fears of the Covid period have ebbed, prompting the government’s treasury managers to tighten the purse strings. Price rises have occurred and opinion is divided on whether these higher consumer costs are within the range of affordability. There have been no protests over fuel prices like those that characterised Modi’s first term and any outcry on this score has been muted. This situation may have been partly influenced by a feeling of energy security. Russian oil supplies in the last three years have definitely contributed to this sense that India shares with China, Hungary and Slovakia.

However, the new year has brought new challenges with the government willing to say very little about buying oil from Russia. But the economy with words on this issue for strategic reasons cannot hide the realities on the ground.

At the India Energy Week in Goa last month, for example, Russian presence was scant. At the same event last year in New Delhi, Russian was the lingua franca in conference lobbies and at bars in hotels where the delegates were put up. For sure, Russia is in retreat on India’s energy platform.

Who is taking the place being vacated by Russia? Prime Minister Mark Carney’s visit to India next month is yet to be officially announced, but Canada unequivocally signalled in Goa that big deals will be signed during that visit not only for oil and gas, but also for uranium and other minerals. The other country that will step up to compensate for the Russian void is the UAE. Which is why Modi’s aim is to ensure the not-so-easy goal of energy independence.

K P Nayar | Strategic analyst

(Views are personal)