It’s a new year, but the debates are old. In January 2024, Nationalist Congress Party leader Jitendra Awhad had declared in Maharashtra’s Shirdi that Lord Ram must have eaten meat during his 14-year exile because he could not have been a vegetarian in the jungle.

Awhad should have curbed his enthusiasm. It is not very wise to project our own appetites and limitations onto others. Lord Ram could have easily survived on fruits, roots and tubers—as countless ascetics have done. We don’t know for sure. It is speculation laced with modern biases.

But in India, speculation fixates on the mythical past, not the probable future. Our sense of time has always been a little warped because we suspect, sadly, that the best has already happened. The future as nostalgia.

Awhad’s remarks added decibels to the cacophony over a proposal to ban meat and alcohol on January 22, the Ayodhya Ram Mandir consecration day. No slaughter of the animals, then. Before we go further, we must clarify: the proposed ban is for that single day, just in and around Ayodhya. Meat delivery, however, is banned indefinitely as an ‘administrative measure’.

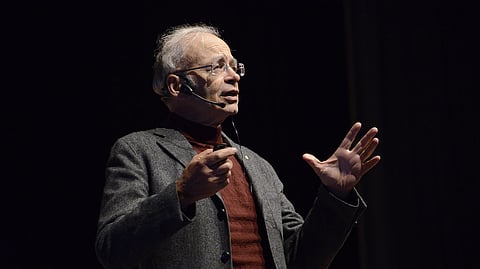

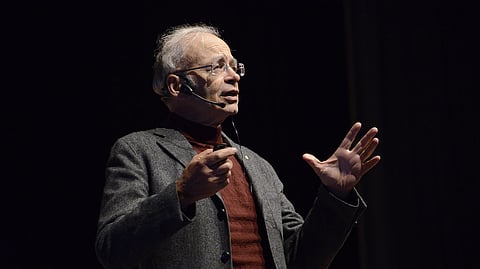

One of the great utilitarian philosophers of our time is Peter Singer. He disputes the existence of any god—Christian, Jewish, Islamic or Hindu—because a truly beneficent and omnipotent deity would have protected not only humans, but also animals—which god supposedly created—from pointless suffering.

Singer’s gaze turns to factory farms, those grim assembly lines of agony where billions of animals endure lives of confinement before the blade. And while they wait, they are all sentient enough to know it’s the end.

Liberals, ever vigilant against state overreach, do not subscribe to the view that the State should intrude into personal space, such as dictating what one eats or wears. On the surface, this is a fair position. But liberals often falter when defending that freedom at the expense of another living, feeling organism. How do you justify a pork chop when the pig screamed in the truck?

The best argument in defence of vegetarianism is that it avoids inflicting pain on another breathing thing merely for your fleeting pleasure or convenience. Singer’s 1975 book titled Animal Liberation: The Definitive Classic of the Animal Rights Movement doesn’t preach from a pulpit. It deploys cold logic. If sentience equals moral weight, the species is irrelevant.

In Islam, dietary law meticulously distinguishes halal (permissible) from haram (forbidden), prohibiting pork and blood. Halal meat demands animals be slain in a prescribed manner, with the blood fully drained to purify the flesh. Purity is not just a ‘desi’ obsession with ghee; it’s at play in flesh, too. Halal is clearly a condition of meat consumption.

Similarly, Judaism’s kosher laws define permitted species—those that chew the cud and have cloven hooves—and mandate slaughter methods designed to minimise suffering while upholding ritual cleanliness, a balance of ethics and sanctity. What makes the whole thing insane, of course, is that it is an act of murder.

In Christianity, most denominations impose no strict dietary restrictions; meat consumption, including pork, is commonplace. Exceptions persist, like the fasting traditions of Orthodox Christians or subgroups such as the Seventh Day Adventists, but general doctrine prohibits no meat on theological grounds.

With regard to Hinduism, the picture is far more complex than the recent controversy suggests. Dietary practices have varied widely by region, caste, community, occupation and historical circumstance, defying any monolithic narrative.

The Mahabharata, central to Hindu identity, depicts the Pandavas and Kauravas participating in hunting and meat consumption as integral to Kshatriya life. There is no textual emphasis on strict vegetarianism as a universal code. And they all went to heaven, no matter which side of the truth they fought for.

But the epic is nothing if not a paean to the glories of a very violent war. Which raises the question: if you are licensed to kill humans by the lakhs, why draw the line at animals?

Perhaps ahimsa as a foundational ethical principle in Hindu philosophy remains an aspiration, not an actualised ideal. Which is why killing an animal is branded ‘non-Hindu’, but conducting war is, well, kosher.

The present meat ban around the Ayodhya temple precincts—a policy defended in the name of respect and sentiment—has unstated violent consequences: a kind of slaughter by economic strangulation. Street vendors, cooks, transport workers, cleaners, hotel staff and daily-wage earners—many of whom belong to Muslim and Dalit communities—have suffered acute income loss as their livelihoods have been sacrificed on the altar of piety.

What begins as a gesture intended to signal piety transmogrifies into an economic penalty imposed on those at the margins of society. Even from a conservative point of view, this is violence—ahimsa inverted.

An ideal way to handle the situation would have been financial compensation to those bearing the brunt of the state’s idealism. If animals are a priority, surely the humans who live off killing them are no less in value?

What the Uttar Pradesh government should be doing is to show an alternative means of livelihood to its people affected by its mythological aspirations to ‘pure’ life. Unless they believe starving a human is pretty much the same as killing a chicken. If so, they have arrived—perhaps to the ironic applause of Singer.

C P Surendran | Author whose latest volume of poetry is Window with a Train Attached

(Views are personal)

(cpsurendran@gmail.com)