India’s self-positioning in the world of diplomacy, realpolitik and superpower-gaming became clear with its response to the US attack on Venezuela and the kidnapping of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores.

“Recent developments in Venezuela are a matter of deep concern. We are closely monitoring the evolving situation. India reaffirms its support to the well-being and safety of the people of Venezuela. We call upon all concerned to address the issues peacefully through dialogue, ensuring peace and stability of the region. The embassy of India in Caracas is in contact with members of the Indian community and will continue to provide all possible assistance.”

The entire text is anodyne, strenuously crafted to hold no one responsible, no event referenced and no specifics noted. This is neither non-alignment at work nor multi-alignment. It just shows India standing nowhere—not on proud land, or a boat guided or adrift, or straddling two boats tugged apart by different currents, or in charge of the mast.

All countries are watching Venezuela in particular and Latin America in general with “deep concern”, just as they are “closely monitoring the evolving situation”. During conflicts, India has always called for addressing “issues peacefully through dialogue, ensuring peace and stability of the region”. These words are regurgitated, nearly verbatim, following every single time stressor event—except those in the immediate neighbourhood where India stands to gain or lose face or its muscularity seems under threat.

This places India, with some sinew though it may be, inside a local satrapy zone. It appears to be at pains to de-assert itself from big-country, tough-guy weltpolitik. This is not where we were, not where we should be and not where we want to be.

As for the last sentence, Indians in Venezuela are few and far between—about 50 non-resident Indians and 30 persons of Indian origin, according to data from the ministry of external affairs. According to the Indian Association of Venezuela, there are fewer by far—barely half-a-dozen Indian families settled across the country. There are no reports of any of them having asked the Indian government for help, or of the Indian government having proffered any aside from “strongly” advising “Indian nationals to avoid all non-essential travel to Venezuela”.

Whether or not it validated or condemned Maduro’s exfiltration by the US, nearly every other country remarked on the need to adhere to “international law”—a backdoor critique of the act of invasion itself. India, pointedly, did not even mention that hallowed term, despite that it has been hollowed-out, its impact analgesised by repeated Big Power abrogation over the past five years.

This is not about playing it safe in the face of Donald Trump’s overheated, skittish tariffism—the resolution of which is long past its due-by date, but about India’s place in the world. On the very day that the MEA delivered its press release on Venezuela—the day after the attack—Trump threatened to raise tariffs on India “very quickly” if it didn’t stop buying oil from Russia—although India’s imports of Russian crude fell by 40 percent between June and December 2025. In a fundamental sense, India’s stance on Venezuela has done nothing to mollify Trump’s cartoonish Ukrainianist torment at the defiant circulation of Russian oil.

So, why substitute principle with pampering? Russia and China both have spoken out in favour of Venezuela’s Bolivarianism, which includes tenets of thought and action that India has always declared it holds dear: patriotism, socialism, anti-imperialism, state-planned economy, social welfare and participatory democracy. Most of the Global South would swear by these pillars of statal rectitude.

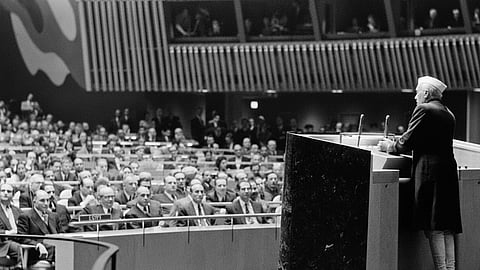

Jawaharlal Nehru is anathema to the current dispensation, which nevertheless shares values with Nehru that he shared with the Italian national icon Giuseppe Garibaldi who shared Bolivar’s core principles of fierce autonomy and republicanism. The scalping that the US has carried out—decapita al jefe, never an act without consequence in Latin America—falls neither within India’s foundational principles nor wherewithal.

While declaring that he was unambiguously among those who “do not obviously accept the communist ideology”, Nehru called out Nato as being “one of the most powerful protectors of colonialism”. Although separated by a vast philosophical and political gulf from the two superpowers of his time, his prescription remains indelibly relevant whether India self-describes as non-aligned, multi-aligned or an opportunistic fade-in or fade-out of one or the other.

He had warned B N Rau, India’s representative to the UN Security Council, in a letter in 1950 about the UK following “a curious and vacillating policy, trying to influence the US but ultimately being influenced by it, for obvious reasons”. To reward Nehru with prescience, all we have to do is replace the UK with present-day India.

“So we must take a complete view of the situation and not be contradictory to ourselves when we talk about colonialism, when we say ‘colonialism must go’, and in the same voice say that we support every policy or some policies that confirm colonialism. It is an extraordinary attitude to take up.”

And this is why India’s milquetoast attitude to the US’s invasion of Venezuela and the kidnapping of its president—the first ever such abduction of a sitting, elected head of state by another country—is an extraordinary attitude.

Kajal Basu | Veteran journalist

(Views are personal)

(kajalrbasu@gmail.com)