The routine of raids by the Enforcement Directorate or the Central Bureau of Investigation in search of evidence of crime and money laundering is not shocking. Not even when such raids are conducted on politically consequential persons from the opposition prior to an election.

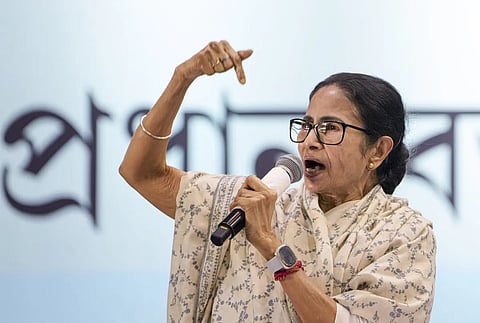

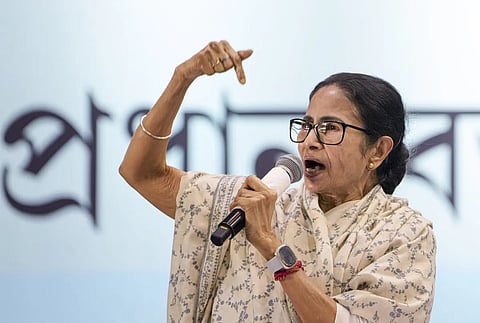

But it is indeed shocking—if not scandalous—when a sitting chief minister is accused of “gross obstruction” and theft of crucial data, files and evidence by the ED. On January 8, when Mamata Banerjee stormed into a building an ED team was raiding because it housed an office of the Indian Political Action Committee or I-PAC, a consultancy advising the Trinamool Congress, she had her reason ready: “I intervened as the TMC chairperson, not as chief minister. They came to steal my party data. I will expose everything if needed.”

In response, the ED was compelled to issue a denial: “The search is evidence-based and not targeted at any political establishment. No party office has been searched. The search is not linked to any elections, and is part of regular crackdown on money laundering.” The central agency went to the Calcutta High Court and then the Supreme Court, accusing Banerjee of “theft of digital devices and other evidence, and wrongful restraint and confinement of central government officers”.

The court hearings as well as the West Bengal government’s caveat—that “such targeted seizure amounts to an impermissible intrusion into TMC’s right to privacy under Article 21 and its constitutional right to participate meaningfully in the democratic process under Article 19”—have set the stage for a litigation that’s likely to proceed at the regular pace of such contests.

There are, however, two sides to the incident—the legal and the political.

The ED is essentially saying that it acted independently and that its search of the I-PAC office and its co-founder and director Pratik Jain’s residence are “not linked to any elections”. In other words, it is defending its action from the accusation levelled by Banerjee. To go on the defensive after an aggressive move is a sign of weakness.

Banerjee’s counter-attack raises a fundamental question: are public institutions neutral or are they subject to pressures exercised by ruling regimes? The question is not limited to central institutions like the ED; it also addresses the role of the West Bengal police on the one hand and the impartiality of adjudicating institutions on the other. By broadening the context of the raid into an aggressive act violating free and fair participation in the democratic process under Article 19, the Banerjee government has questioned the role, responsibility and conduct of a number of public institutions including the Election Commission.

The CM’s latest letter to the Chief Election Commissioner on the special intensive revision (SIR) of rolls, released on January 12 along with a petition by TMC MP Derek O’Brien, challenges the commission’s role as a law-abiding institution. The petition demands that the EC “stop issuing instructions for compliance by the booth level officers (BLOs) and other officers in the SIR exercise through WhatsApp or other such informal channels”. It also calls on the judiciary to declare all such instructions issued so far as illegal.

Banerjee’s letter points to “internal record-keeping deficiencies” and complains: “Such administrative lapses are being unfairly forced upon citizens, causing severe harassment and resulting in the denial of their constitutional rights. This defeats the very objective of the SIR, which is intended to strengthen and purify the electoral rolls, not to exclude genuine and eligible voters.”

Sections of voters, sportspersons who have represented India, and functionaries attached to the EC for SIR work have protested against what they perceive is wrong with the process. The support these complaints provide to Banerjee is the political context in which she has blamed the BJP and the Union home minister, whom she has called “nasty” and “naughty”, for the timing of the ED raid. She has contended that I-PAC’s Kolkata office was effectively a TMC back-office where sensitive and confidential information as well as some SIR details were kept.

At the outset, by labelling the ED raid and the SIR as politically motivated, Banerjee has repositioned herself to represent victims. That list includes hapless voters required to prove their identity, protesting BLOs and electoral registration officers (EROs), as well the West Bengal Civil Service (Executive) Officers’ Association, which pointed out that the “suo motu, system-driven deletion of electors” under SIR bypassed the legally-mandated role of EROs. In doing so, she has taken over the narrative and reset it.

Till the BJP comes back with an appropriate riposte that can counter the perception Banerjee has created of the Centre’s victimisation of all things Bengali—from language, internal and cross-border migration, culture and identity to the subtleties of its social and political past—the current score in the run-up to the state assembly battle indicates she has surged ahead.

The ED raid, SIR process and the Bengali-Bangladeshi-ghuspethiya (illegal immigrant) conflation have not created the political advantages for the BJP they ought to have. Local party leaders are on the defensive. It is as though they are waiting for direction from the high command—which could come this weekend, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi visits West Bengal.

Shikha Mukerjee | Political commentator

(Views are personal)