When none less than the Prime Minister takes note of ‘bhajan clubbing’, it is time to deconstruct the cool. Speaking in his Mann Ki Baat broadcast last week, he called it a powerful blend of devotion, culture, spirituality and modernity, mentioning Gen-Z to make sure the young and the restless heard him out.

Trendy bhajans are not exactly new to me, though the phrase and the more evolved structure are. When large groups, especially of youngsters, come together in a community event to sing praises to gods, bhajan clubbing gets the ‘sober rave’ tag in a Hindu package. What is new is the high-energy and nightclub-like atmosphere along with a no-alcohol, all-clean feel.

We now have fancily-named bhajan groups like Backstage Siblings and Keshavam. What’s more, their concerts carry ticket prices that resemble club gigs. They are not your everyday free session at the local temple.

The phenomenon took me on a reverse swing in time.

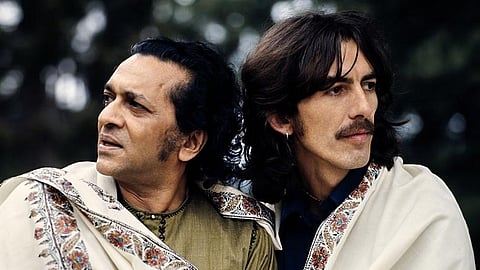

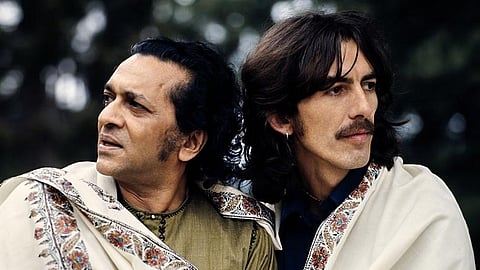

I had my own brush with bhajan cool in the 1970s and 80s when The Beatles era spawned its early seeds. Guitarist George Harrison embraced Hinduism with a zeal that coincided with the rise of the Hare Krishna movement. As a youngster, I heard 'I am missing you', produced by Harrison, composed by Pandit Ravi Shankar and sung by the sitarist’s sister-in-law Lakshmi Shankar. The song expressed a longing to encounter Lord Krishna with English lyrics: “Though I can’t see you, I hear your flute all the while.” Frankly, I found it somewhat amusing, though melodic, and not quite spiritual, especially as it played as part of Western pop music shows on All India Radio.

Then in 1981, Afro-rock band Osibisa staged a live show on the India Gate lawns in the heart of New Delhi and sang ‘Raghupati raghava raja ram’ (officially titled ‘Joy of Om’) that kept spiritual Indi-pop bubbling amid a growing fascination for rock.

Spiritual pop goes back in time. Lucknow-born Cliff Richard, who spent his early childhood in Calcutta, embraced Christianity publicly at a rally by American evangelist Billy Graham in 1966, putting behind his hits like ‘Bachelor boy’ and ‘Summer holiday’. His guitar embraced Christian gospel music.

Hinduism was not far behind. In the early 2000s, I saw a bhajan-club act closer to the contemporary version in suburban Bengaluru at the 250-acre Art of Living headquarters founded by Sri Sri Ravi Shankar. The evening saw long-haired rockers wielding electric guitars singing energetic bhajans to thunderous claps.

Looking back, I found Harrison’s plaintive ‘My sweet lord’, released in 1970 soon after the Beatles split, truly devotional because of its rhythmic chanting that blended “Hallelujah” with “Hare Krishna” in a non-denominational spirituality. It seemed to go beyond the shifting sands of cultural modernity.

There is a spiritual logic and modern science to this that deserves attention. I have attended meditation sessions led by followers of Paramahansa Yogananda, which were preceded by simple words sung in chants that made way for long spells of silent meditation.

“Chanting is half the battle,” Yogananda famously said. He released a book titled Cosmic Chants that contained songs that had a clearer purpose to invoke devotion. The guru said loud chanting was a good start to meditation in creating a “magnetic flow”, but advised transitions into whisper chanting, mental chanting, subconscious chanting and what he called “superconscious chanting”.

Yogananda said: “Sound or vibration is the most powerful force in the universe. Music is a divine art, to be used not only for pleasure but as a path to god-realisation.” That reminds one of Carnatic composer Thyagaraja’s description of god as “Nada Brahmam” (Sound as the divine).

I find chants spiritual when done in a coherent, enchanting fashion, irrespective of their origin or religion. I like listening to Gregorian chants that follow Christian traditions, and in a strange way, found Freddie Mercury’s chanting chemistry with the crowd at London’s Wembley Stadium in his Live Aid concert in 1985 uplifting in a soulful way. After all, the rock bands were raising funds for famine-hit Africans and nursed charitable thoughts.

I also find solace in the soulful 'Dunya Salam' by 1 Giant Leap featuring Senegalese singer Baaba Maal, which praises god as Allah in an Islamic prayer. Its lyrics set to a haunting tune are like an Afro version of John Lennon’s piano ballad for peace, Imagine.

On a more orthodox groove is Jai Uttal, an American devotee of Neem Karoli Baba. Born Douglas Uttal, the Grammy-nominated guitar-wielding singer is called a ‘kirtan artist’ and hailed as a pioneer in ‘world spirit music’, a derivative of the more popular world music genre. He sings bhakti-filled chants on Hindu deities and uses elements of jazz, reggae and ballads.

That takes us to the neuroscience behind chants and meditation.

The US government’s National Library of Medicine says, “The simple act of repeating a sound may increase focused attention while decreasing awareness of bodily sensations. Further, if the repetition of the sound is vocalised, slowed breathing is likely to activate the parasympathetic nervous system,” adding that “even if one is distracted, vocalisation is likely to have positive respiratory and hormonal changes that may contribute to feelings of relaxation and positive mood”.

Bhajan clubbing may thus be just a trendy word for what they call satsang in religious circles and the science behind chants does show the power of congregation as well as health benefits. But there is evidently a need to differentiate between headbanging decibels and soulful chants.

Madhavan Narayanan | REVERSE SWING | Senior journalist

(Views are personal)

(On X @madversity)