The art of winning friends and informing people

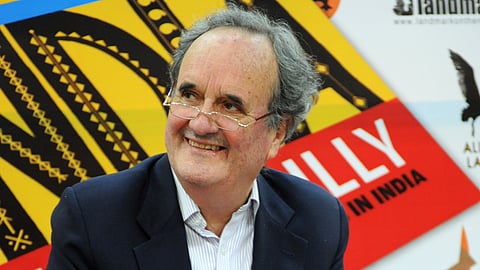

For a generation of Indians like me who grew up listening to his BBC dispatches from the subcontinent, Mark Tully’s voice was synonymous with the gold standard of journalism—unbiased and speaking truth to power as a card-carrying member of the Fourth Estate. This Englishman went on to be known as the “voice of India” and decided to make the country his home for over half a century. At times, I envied him for his Indianness and wondered how he could love my motherland more than I did.

While people knew him as an ace broadcaster and a prolific writer, a few of us who worked with him witnessed his down-to-earth nature, humility and mastery of the art of making friends. I also had the honour of living close to him in the Nizamuddin area of Delhi for 20-odd years and catching an occasional glimpse of him and his beloved labradors in the hard-to-miss, bright-red two-seater he would drive around.

Two years ago, an essay of mine on Indira Gandhi’s communal politics caught Mark’s eye and prompted him to drop off a handwritten note at my place through his driver. The note read: “Needs discussion. I don't have your number. The computer is down. Why not ring to fix a time to meet?” I was thrilled to receive the invitation and promptly scheduled a meeting at his place. Our long, winding discussion covered Hindutva, secularism and the Nehruvian model of secularism—which Mark was not completely convinced by and opposed my endorsement of.

It is ironic that 50 years earlier, at the onset of the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi, I had first become acquainted with Mark’s critical broadcasts against the government that had jailed my father under the Defence of India Rules and the Maintenance of Internal Security Act for 19 months. For my impressionable mind at the time, this perhaps sowed the seed of pursuing a career in journalism. A decade later, in the 1980s, Mark appointed me as a stringer for the BBC, where we covered many landmark events together—the 1989 general elections, the formation of V P Singh’s National Front government, its fall, the formation of Chandra Shekhar’s government in 1990, and the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi agitation.

Mark personified fearlessness and quiet rebellion. He was a staunch proponent of standing up for what he believed was right, whether from outside the system or by effecting change from within. By 1993, he had been the BBC’s South Asia bureau chief based in Delhi for over two decades, yet he did not hesitate to boldly voice his displeasure at the institution’s state of affairs. His scathing remarks about director-general John Birt—lambasting the “culture of fear” and the broadcaster’s transformation into a “secretive monolith with demoralised staff”—led to his resignation in July 1994. His defiance showed that he placed journalistic ethics above all else and was not afraid of walking the talk—one of his many admirable qualities.

A man of extraordinary courage, unwavering integrity and unshakeable commitment to the values of journalism, he became a household name in the region, and an eyesore for many South Asian governments. During the Emergency, he was asked to leave India and returned only once it was lifted in 1977. Again, as Operation Blue Star unfolded in Amritsar in 1984, Mark was asked to leave the city. But in typical Mark Tully fashion, he ensured that the coverage remained accurate and unbiased, adhering to the highest standards. Satish Jacob was on the ground while Mark coordinated from New Delhi.

In an interview for BBC Hindi, I jokingly asked him how he had managed to “secure not one but two Padma awards from the Indian government while continuing to criticise its policies”. An agitated Mark responded: “I didn’t manage it—I was offered, and I took permission from my organisation the first time in 1992 (for the Padma Shri), while in 2005 I was an independent person (when he was conferred the Padma Bhushan). The same thing happened when I got the OBE and MBE from the British government.”

The one reportage from Mark’s career that stands out for me has to be on the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, delivered from ground zero at great personal risk. The event became a turning point in the unravelling of India’s social fabric, and I was part of Mark’s entourage, moving between Ayodhya and Faizabad, racing against the clock to send the dispatch to the BBC’s London headquarters. We were apprehended by a mob of angry kar sevaks who recognised Mark and decided to lock five of us in a nearby temple to avoid disrupting the demolition, planning to “deal” with us later. We were, of course, rescued hours later and lived to tell the eyewitness account.

One of Mark’s last correspondences with me was another note that read: “I hope your view won’t change when you read the draft of my book (autobiography), which I hope will be quite soon.” Alas, I will eagerly wait to see that draft land in my mailbox some day, whenever it is published, and hope another impressionable mind will read it and build upon Mark Tully’s path of fearless journalism.

Long live, Mark. May you rest in peace.

(Views are personal)

Qurban Ali

Senior journalist who worked for more than 14 years at BBC World Service