The architects of our Constitution believed that reservations meant to bring those who have been degraded through centuries of disempowerment on par with the rest of the society was just and necessary. But clearly, they held that perpetuating this arrangement beyond a period was neither desirable nor justifiable. The social medicine they prescribed had a shelf life only of a decade. Caste-based reservations as a state policy were envisaged to end by 1960.

Consider for a while the idea of special provisions and protections as such. It is analogous to the latitude extended to infants and dependent children in a home. If so, the enjoyment of such provisions has implications for one’s situation, stature and self-image. Dependent children, for instance, are not granted the sort of freedom and rights that adults may enjoy. One cannot have special privileges and general rights at the same time; just as one cannot be an infant and an adult at the same time. An infant claiming adult rights provokes disapprobation. At the same time, it is cruel and callous on the part of adults to neglect or resent the special needs of infants, which could imperil their well-being altogether.

I agree with the framers of our Constitution that social disparities and disabilities have to end, and cannot be posited ad infinitum as an alibi for perpetuating what is politically expedient. Empowering provisions are envisaged to achieve a goal: to proactively compensate inherited disabilities. They cannot be privileges in perpetuity. If you undergo an orthopaedic foot surgery, you will be prescribed a crutch for temporary use. All crutches are, by definition, interim and dated accessories. Unless wisely used, they could perpetuate one’s general disabilities in the process of mitigating a special disability. Empowering provisions, in other words, cannot be converted into alibis for perpetual disability. Means for empowerment cannot be perks pegged on unending disempowerment. The fixing of a deadline for terminating this provision was eminently rational.

The excuse, if any, for perpetuating reservations is that the anti-Dalit socio-cultural attitudes, customs and conditions continue unabated. The provision of reservation has failed to bring about the desired amelioration in this respect. Caste continues to alienate and degrade. If so, reservation could well be a failed instrument that merits to be discarded summarily, or revisited surgically.

Why has this measure failed as much as it has? We are experts in blame game. The likes of Shashi Tharoor are eloquent in grilling the British. Of course, they deserve to be damned. But is that the reason why we are the way we are 70 years after their departure? America too was a British colony. It was poorer than India at the time of shaking off the British yoke. Ever heard of America weeping over being colonised by England? America caught up with England in quick time. But Britain still serves us as an alibi for our failures and also as a safe haven for Indian patriots who, having looted us enough, are pleased now to spare their Motherland.

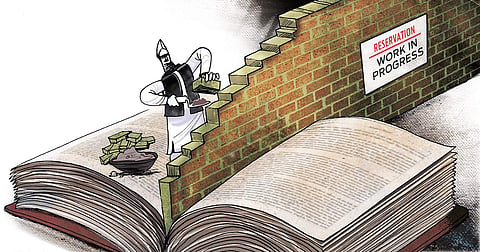

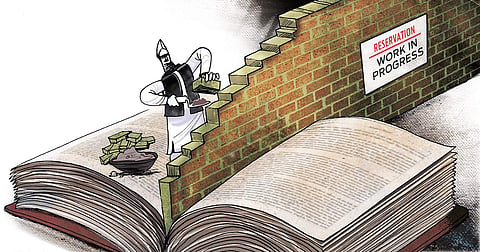

Reservations perpetuate social cleavages without conferring the desired benefits to intended beneficiaries, especially the needy among them. Reservations are an invisible wall. And invisible walls are harder to scale than a sky-kissing stone wall. It breeds a crippling psychology of inferiority. It is not good for a society to be fragmented for any reason whatsoever. It does not do any good to anyone to be on this side or that side of the wall. What helps is the elimination of the wall, provided those on both sides are ready and liberated enough to embrace each other as fellow human beings.

Protective and empowering provisions are predicated on two broad considerations vis-à-vis target communities. First, giving effect to the need and the right of every individual, group and caste to develop and attain dignity. Since equality is one of the shaping principles of our Constitution, reservations are hitched to creating an equitable and discrimination-free social order. The framers of the Constitution estimated that this goal could be achieved, and ought to be achieved, in a decade.

The second purpose was to remove, through educational and employment opportunities, social disabilities including deeply entrenched invidious attitudes towards inferior castes and the violation of their social, economic and political rights. Even three decades ago, Dalits in several Indian hinterland villages used to be disallowed to vote by their caste overlords, unless they could be trusted to vote for designated candidates. It is a matter of some consolation that this slur is now a thing of the past.

The foremost hindrance to a principled and justifiable abolition of reservation is the attitude of the dominant social and religious interest groups towards their presumably inferior fellow human beings. Virtually nothing has changed in this respect since 1947. The framers of the Constitution, in prescribing a ten-year period of validity for reservations, could not have—at least do not appear to have—taken this aspect of the matter adequately into consideration.

This brings us to the supreme irony of the reservation dilemma. The principal excuse for continuing reservations is the attitude of those who militate against it. The Dalits—barring the creamy layer among them—do not have a level playing field in society or public life. Their cultural, social and religious stigmas continue unabated. This was presaged by the plight of Ambedkar who, as one of the important officers in the service of the Maharaja of Baroda, was insulted and socially boycotted by the society and by his own subordinate staff.

It is desirable that reservations be abolished soonest. For that to happen, it is imperative that the atavistic anti-Dalit social, religious and cultural reservations lurking in upper-caste attitudes, customs and practices be first eradicated.

Valson Thampu

Former principal of St Stephen’s College, New Delhi

Email: vthampu@gmail.com