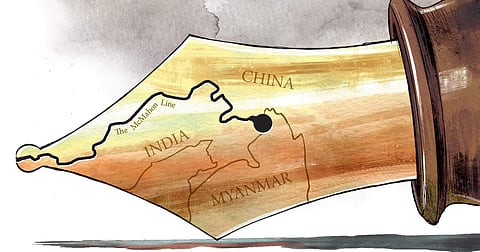

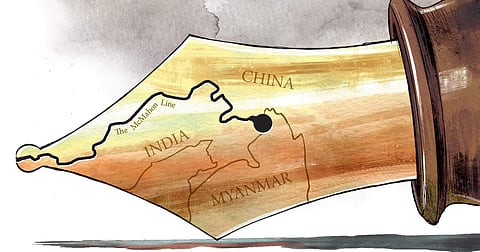

More than a century after the McMahon Line was drawn at the tripartite Simla Convention of 1913-1914 between British India, Tibet and China, uncertainty over the Indo-China boundary in the Northeast remains a festering sore. In the Western sector, unlike in the Northeast, there is no treaty that demarcates the boundary between the two countries. So the issue will have to be settled differently.

But the McMahon Line is not without problems. It has a contested history, much of it a British colonial legacy, which from all indications is what is holding up a final truce between the two Asian giants. India was a signatory of this treaty and endorses its legitimacy; China, left out of the treaty-making exercise, continues not to recognise the line. On the question of its validity also hangs the knotty question of whether Tibet should be considered a part of China at the time of signing, or an independent nation with international treaty-making power. The line was agreed upon through exchanges of notes between Henry McMahon and the Tibetan plenipotentiary Lonchen Shatra. The Chinese plenipotentiary, Ivan Chen, was left in the dark.

The intriguing question is why this was done in this manner. This is best answered by well-known scholar Alastair Lamb. It had to do with the British phobia that Tsarist Russia, gobbling up Central Asia towards the end of the 19th century, may take Tibet, bringing the rival next door to their prized colony, India. A cold war in the region, the Great Game, ensued between the European empires. In 1907, as part of this rivalry the British forced the St. Petersburg Convention on Russia, greatly weakened after a humiliating naval defeat in 1905 against a rising Japan, though the power equation in Europe was shifting and Russia had become a British ally.

Among others, the 1907 St. Petersburg Convention required both the British and Russians to keep out of Tibet and if any of them had any emergent situation to deal with, to do so through the mediation of a third party the British did not see as a threat at the time—China. Lamb satirically noted of the summit that, as in Judo, the Russians used the weight of the British to throw and defeat it. Hence, in the 1913-14 Simla summit, when Britain needed to urgently settle India’s northern boundary after the fall of China’s Manchu dynasty, it had to invite the Chinese to participate so as not to displease the Russians.

But the boundary was made only between Tibet and India, which is one of the reasons why the British chose not to publish the agreement in the Atchison’s Treaties immediately, fearing Russian protest. It was published only in 1938 after the Communist takeover of Russia in 1921 and the new regime’s abrogation of most Tsar-era treaties.

The above controversies around the McMahon Line are well known. What is the way forward? The answer may well be in the way other boundary lines contiguous to the Line were settled by Myanmar and Nepal with China. The case of Myanmar is particularly interesting, for it was part of British India at the time of the Simla Convention, and its boundary with China was an extension of the India-China boundary. In 1960, as Neville Maxwell notes in his controversial but influential book India’s China War, the then Chinese premier Chou Enlai travelled to Rangoon to meet his Burmese counterpart U Nu and reached an agreement to redraw and ratify the same boundary with a little give and take, erasing its colonial legacy to make it their bilateral treaty.

On the same trip, the Chinese leader reached Delhi, but the Indians held the McMahon Line was not open to renegotiation. From India the Chinese flew to Nepal, where too an agreement was reached on the boundary, including to divide Mount Everest with its north face going to China and south face to Nepal.The moot point is, for all the posturing such as in Arunachal Pradesh, what China probably wants could be just another treaty to ratify the existing boundary with a little give and take, just so that the historical baggage of McMahon Line that it objects to is purged.

There is yet another chapter from the colonial history of this region which again suggests Beijing’s interest is an unambiguous acknowledgment of its complete sovereignty over Tibet more than the contents of British-concluded agreements with Tibet. In 1904, when Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India, became convinced the 13th Dalai Lama was leaning towards Russia, he sent the Younghusband expedition to teach the Tibetans a lesson. Col. Francis Younghusband and his troops invaded and butchered the Tibetans, but the Dalai Lama fled to Mongolia before the expedition reached Lhasa. Still, Younghusband forced the humiliating Lhasa Convention, 1904, on the Tibetans, including the imposition of a war reparation of `75 lakh on the Tibetans to be paid `1 lakh a year; Chumbi Valley, wedged between Bhutan and Sikkim, was to remain with India.

The Chinese protest was peculiar. They wanted the treaty to be renegotiated with Peking (Beijing) for it to be legitimate and convinced the British to have a summit in Calcutta on the matter. Under Lord Curzon it broke down for he wanted an unconditional Chinese ratification of the Lhasa Convention. Luckily for the Chinese, Curzon’s term as Viceroy ended in 1905 and his successor Lord Minto was more lenient and the Calcutta summit resumed in Peking in 1906, resulting in the Peking Convention which virtually had all that the Lhasa agreement had, but was between the British and the Chinese, and not the Tibetans.

The Chinese also negotiated over the war reparation on Tibet, by then already reduced to `25 lakh as a leniency gesture by the British, to be paid up by Peking in three instalments. They cleared the amount and in three years, Chumbi Valley was back with Tibet. Thus, the Chinese objection had little to do with the content but the protocol.