Sometime in the early 1980s, my friend and I spent a few days at Sarvodaya leader Vinoba Bhave‘s ashram at Paunar, near Wardha in Maharashtra. Mornings were spent in the ashram’s garden plucking fresh vegetables for the day’s meals. Those two hours every morning were like being in the gardens of Babel. All sorts of languages fell upon my years. Apart from the Hindi and Marathi officially spoken at the ashram, there was Tamil, Telegu, Malayalam, Bengali, Punjabi and some foreign languages including French, Spanish, German, Russian and, of course, English that bound all inmates, foreign or Indian, in a common thread of understanding.

It was a great lesson in communication, commonality of various tongues and the unity in the diversity of languages. When I returned and related my multilingual experience to my professor at university, he said something so profound that it has stayed with me through all these years. “Languages are supposed to unite. In this country, they only divide.” But not just in this country. Pakistan, which had separated from India over religion, ended up dividing itself again over language. They attempted to impose Urdu upon the Bengali-speaking people of East Pakistan, who inevitably rebelled and Bangladesh came into being. In Sri Lanka the problem of Tamil militancy began in response to the imposition of Sinhala over the entire population. It took years of a bitter, bloody separatist movement and the quiet withdrawal of the one nation, one language policy to defeat terrorism. Lanka could as easily have lost the Tamil-speaking territories.

Elsewhere, the end of communism, which had kept Czechoslovakia together perforce, led to its breaking into two—the Czech speaking Czech Republic and the Slovakian speaking Slovakia. But in the three countries that Yugoslavia broke into over religion and ethnicity, Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian are all national languages, in addition to Hungarian, Romanian, Russian and some other Slavic languages officially recognised as regional languages in some provinces. But in undivided Yugoslavia, apart from Macedonian and Slovene, a mix of Serbo-Croatian was its official language. Somewhat similar to Portuguese-Spanish, Konkani-Marathi or Hindi-Urdu, which themselves are derivatives of Persian-Arabic.

While on a mid-career course in journalism in Paris, my unilingual course mates were amazed at the ease with which the Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Nepali and Indian students slipped from English to Hindi, Urdu or Tamil in the course of a single conversation and yet made perfect sense to each other. They asked, “What is that you speak? Is it Indian, Pakistani, or Sri Lankan?” We laughed with pride and said there was nothing like a single Indian, Pakistani or Sri Lankan language. But I was the proudest, because while all the other South Asian countries had two or three official languages, my country had 22. They all found it mind-boggling when I said India had about 1500 mother tongues and even more dialects. When they discovered I spoke five Indian languages to varying degrees of fluency, the minds of even my South Asian colleagues boggled.

Back at the Paunar ashram, a door—which is darwaza in Hindi/Urdu—was perfectly understood by a Slavic resident in whose language it was dwarza. However, when the Malayalee garden supervisor called upon us, in Marathi, to pull up some pineapples, almost everybody understood; practically no one needed a translation. For the word for pineapple in most languages, Indian or European, is ananas, with only slight variations in pronunciation. Where did that come from, I wondered—Sanskrit, the root of all Indian languages, or Latin, the root of European? Indo-Aryan, anyone?

At home, too, we spoke many languages. My parents had two languages between them, but our lingua franca was English with a smattering of Hindi or vice-versa. However, when I moved to Bombay, I was shocked by Bambaiyya Hindi, which was a mix of Hindi, Urdu, Marathi, Konkani and Gujarati. When I went home for a brief vacation, my mother, who had helped my father pass his Hindi rashtrabhasha exams with flying colours, thought I was speaking of bitter gourd—karela—when all I meant was that the task she had set me was done. After her reprimand at mauling the language, I promised not to speak Bambaiyya, but I must admit it is a fun language and very expressive.

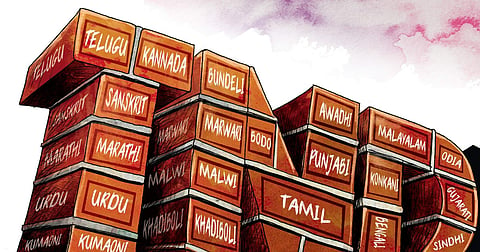

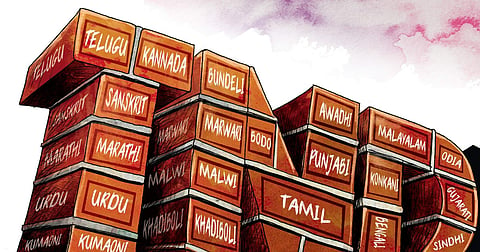

So it is just as well that Union Home Minister Amit Shah has backtracked on his plan to impose Hindi on the rest of us in pursuance of the BJP’s ‘Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan’ policy. For even in the Hindi heartland, Hindi is not the lingua franca. Rajasthan speaks Marwari, Malwi and Mewati among other dialects, which are difficult for a pure Hindi speaker to follow. Uttarakhand has Garhwali, Kumaoni, Jaunsari, a smattering of Nepali apart from Hindi and Urdu as official languages. Uttar Pradesh also speaks Awadhi, Brijbhasha, Khadiboli and Bundeli—is it any wonder, then, that nearly 10 lakh students failed their board exams in Hindi this year? Bihar speaks mostly Bhojpuri and Mythili which until recently was written in the Bengali script. Then again in Madhya Pradesh we have Awadhi and Bagheli with Chhattisgarhi in the neighbouring state being a mix of the two. So how many people really speak text book Hindi? Like the linguist Frank Smith said, one language restricts us to a single corridor. Let’s open our doors to the world with many more.

Sujata Anandan

Senior journalist and political commentator

Email: sujata.anandan@gmail.com