An enduring characteristic of the post-Westphalian era of nation states is the concept of power balance. While this largely played out in Europe where nations started respecting fixed borders, the concept gathered steam in the centuries that followed and became firmly embedded in geopolitics. Large and powerful states, as well as less powerful medium and small states, play this game in varying degrees. Large states seek clients or proxy nations for their pursuit of balance whereas small and medium nations seek to balance the influence of big nations, particularly if they share borders or are in their neighbourhood. The dilemma of balancing deepens when small nations develop certain dependencies covering the whole interface of bilateral ties with a large neighbour.

The Indian sub-continent is a classic example of the manifestation of balancing ties between nations in the post-1947 period, triggered by the creation of Pakistan. British imperial legacy was handed over to an eager US, taking over the mantle of leading the Western capitalistic democracies during the Cold War and subsequent contest with the Soviet Union to keep communism at bay.

It became obvious to the British-American policy makers that Pakistan will seek an alliance relationship with the West and India will shun such an alliance. Embittered by his “moth-eaten Pakistan”, Mohammad Ali Jinnah sought out the US to counter India. The bitterness in the Pakistani leadership was accentuated by the difficulties in division of assets and government personnel, as India was accused of denying what Pakistan felt was its legitimate share. Adding to this angst was the accession of Kashmir to India and failure to grab the whole of Kashmir, particularly its Muslim-majority area.

Pakistan is the most egregious case of a nation that has sought alliance with powerful nations in its quest for sustaining perpetual hostility against India. Pakistan pursued its alliance with the US during the Cold War. The US saw Pakistan as a useful nation in the underbelly of China and the Soviet Union, two large communist countries. Pakistan sold its narrative as a bastion against communism though its real intention was to arm itself against India. With the end of the Cold War, Pakistan’s reduced relevance was revived for some time during the Afghan Jihad against the Soviet Union. Thereafter, Pakistan allied itself with China when ties with the US cooled. Both China and Pakistan share a common hostile objective viz-a-viz India.

In the Pakistani official narrative, J&K is an unfinished business of Partition. Even today the oft-repeated slogan “Kashmir banega Pakistan” remains an unfulfilled dream. With the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian Constitution, Pakistan’s “dream” has turned into a nightmare.

India’s other neighbouring countries, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka are also playing the China card in varying degrees. The lessons of BRI’s debt-trap diplomacy have been learnt the hard way by Maldives and Sri Lanka. Bhutan remains an exception but the Doklam incident was a reminder of China’s pressure tactics. Nepal has jumped on the Chinese bandwagon and is choosing options that may boomerang on it.

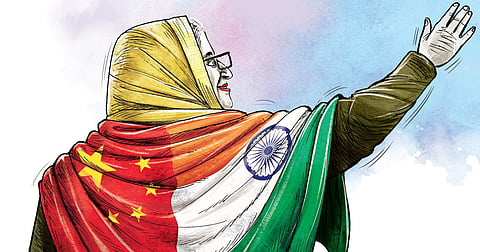

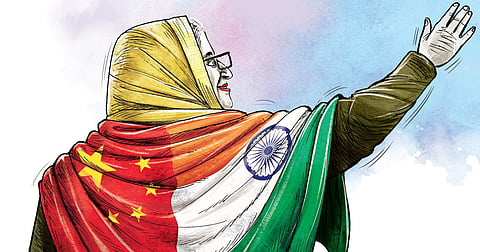

Bangladeshi PM Sheikh Hasina’s visit to China in July once again underlined the balancing act that India’s neighbours generally embrace with alacrity. While India is a neighbour with a shared boundary and centuries of civilisational contacts, China is a rising power, with big bucks to spare.

Bangladesh is playing its cards differently and adroitly. Its development requirements are, indeed, substantial and China and India are both major contributors in funding projects, though China has far more capacity to lend than India. Bangladesh understands this and has deftly attracted development funds from both China and India for infrastructure projects. Bangladesh has joined China’s BRI and is also promoting the BCIM corridor.

India will have to take note of Bangladesh-China cooperation in the maritime sector too. Bangladesh will be facilitating China’s entry into the Bay of Bengal with consequences for India’s maritime security environment.

China’s assistance in Bangladesh’s infrastructure sector is not new. The “Friendship” bridges to improve transport links within Bangladesh and the International Convention Centre in Dhaka were built with Chinese assistance decades ago. China remains the main source of military hardware for the Bangladeshi Armed Forces, though India has instituted a Line of Credit for the procurement of Indian defence hardware. China is stepping up assistance in the digital sector to Bangladesh and we may see Huawei 5G technology introduced there. Security implications could be considerable for us. India is still debating whether to permit Huawei to participate in the 5G rollout.

While China has reiterated its promise of reducing the yawning trade imbalance, it is establishing an Industrial Zone near Chattogram [Chittagong]. China’s manufacturing base in Bangladesh will provide another avenue for cheap Chinese exports into India, since Bangladesh enjoys duty-free access to the Indian market.

Hasina appears conscious of and sensitive to India’s concerns and has put on record at the WEF gathering in China that Bangladesh will not step into any “debt trap”. She has also said Bangladesh’s ties with India are “organic” and goes beyond a few billion dollars. She is being cautious and has openly said that Bangladesh has no military ambition and seeks out China as development partner only. With Hasina in power, India won’t be too anxious in the near future.

Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty

Former Secretary in MEA and ex-High Commissioner to Bangladesh. Currently a Visiting Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

Email: pr.chakravarty@gmail.com