A few years before he passed away in 2004, in a private meeting with a few journalists at the Hyderabad Raj Bhavan suite, the usually reticent P V Narasimha Rao voiced his regret over the dramatic economic reforms he ushered in during the nineties. The results had not been what he envisioned - the top 10% of the population took most of the gains while practically everyone else was left behind. Most of us, India’s middle class that is, were kept busy by the shiniest gadgets and the big, swanky malls. The subsequent decades have hardly been different as the market economy managed to tighten its grip.

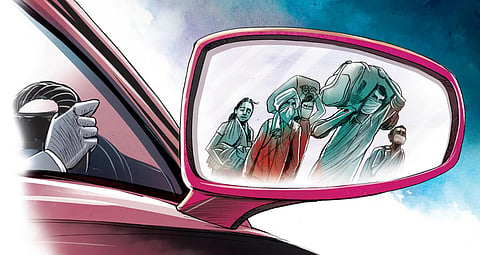

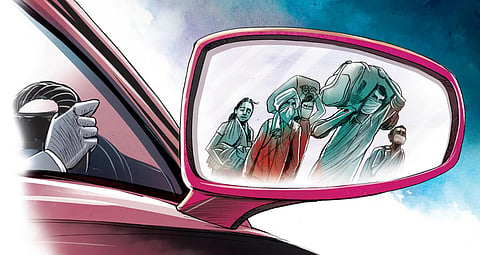

As thousands of migrants leave our metropolitan cities on foot to go back to their villages with back-breaking loads, I am haunted by that conversation.

To what extent has the crisis we’re witnessing today been in motion for years? Life has been thrown out of gear in a matter of hours following the sudden imposition of lockdown, yet it means something dramatically different for some, as those who can afford to stay home begin exchanging ideas to kill time and the particularly inventive consider making money out of the pandemic. Through every conversation, debate and sermon alike, whether interpersonal or on television, the same question keeps surfacing: How have we, as a society, come to this grossly inequitable situation, and are seemingly comfortable with it? This is not to suggest that this is, in any way, a new phenomenon. Indeed, almost every Constitutional debate was centred around social and economic inequality. But what was relegated to the realm of pundits in the post-reform era has now become impossible to ignore in the COVID-19 moment.

Consider this: The latest UN Human Development Index ranks India among the top three countries where inequity is rising at an alarming pace. This is hardly surprising. For almost two decades (2000-2018) the bottom half received 10-15% of the total income. At the same time, with 138 billionaires, we are now next only to China (799) and the US (626). Less than half of India’s urban workers have a regular, salaried job. The rest are drivers, vendors, domestic workers and the new-age digital gig economy workers, all with zero social protections. The two glittering cities, Delhi and Mumbai, have around half of its populations living in slums where 50-100 people are often seen sharing a single bathroom. Eight-lane expressways and bullet trains find their way into budgets, but not housing for the poor. New research reveals how India is in a way unique in the creation of its billionaires.

It is one of the few countries in the world where billionaires are aided by the state with a majority of them representing sectors such as telecom, mining and construction, largely thriving from the benefits doled out by the establishment in the form of free/subsidised land, allotment of mines and so on.

In an economy largely driven by the market, the state has been slowly giving up its primary duty of being custodian for the people at large. It has chosen instead to protect the interests of a privileged few in the guise of trickle-down economics. Yet, in the past few weeks, we have witnessed corporates and the ultra-rich show up with crores of rupees in donations, eager to be the face of the coronavirus solution. This is, of course, much needed funding in this current moment.

At the same time, we should be cautious of what it represents. What’s the business model of being a do-gooder? How are we seeing corporate foundations pledge tons of money as we simultaneously witness layoffs?

In the 2019 book Winners Take All, Anand Giridharadas, a former McKinsey consultant, argues that the elite follow a “win-win formula”, where they are willing to fight for so-called equality, except in ways that threaten their position at the top. This applies as much to corporates (an online retailer who pays as low as Rs 15,000 a month to a delivery boy, but generously donates a few hundred million as aid) as to organisations that profess to do good work without actually challenging the system. Let us for a moment set aside suspicions over intent. Should our gravest problems be solved by consultants, tech companies and corporates instead of public institutions? In the Indian context, the state abandoned its role in two critical areas - health and education.

Consider health: Some of the best doctors are a product of government-funded medical colleges, but less than 10% of them want to work in a government hospital. The state provides medical insurance for the poor and corporate hospitals are the ones that profit from it (the very same corporate hospitals now generously contribute to relief funds). When a crisis unfolds, workers and doctors of neglected government hospitals are once again on the front line.

It’s no different in the field of education. The best teachers would be those who studied at public-funded institutions but later prefer to work for private institutes (like hospitals, quite a few corporate educational groups too handed out fat cheques for the relief fund).

This is a moment for us to reimagine the kind of systems we want to build. Real reform is when public good is a duty discharged by the state, one that the polity can hold it accountable to, and not the charity of a benevolent few. Public institutions that have been pushed to the margins are beginning to be revealed as critical solutions to social problems. The demand should not be a return to ‘normalcy’ for it is now impossible to deny that the normal was dysfunctional. (Admission: The writer is as guilty as anyone else)

GS VASU is the Editor, The New Indian Express. E-mail: vasu@newindianexpress.com