A patient reading of the Ayodhya judgment delivered by a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court last November may lead one to reasonably conclude that its discussion on the Places of Worship Act, 1991 (“the PoW Act”) was irrelevant to both the factual and legal matrices of the case.

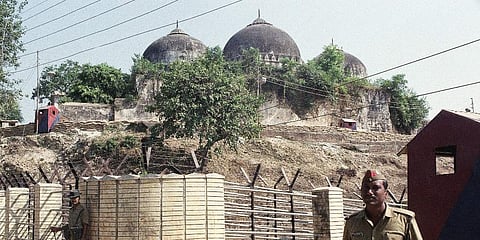

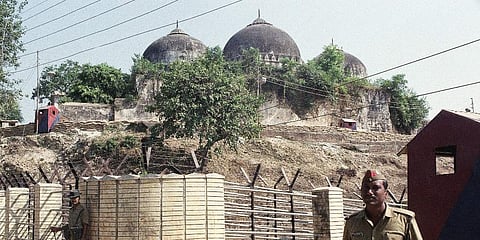

The appeals before the Supreme Court arose from the 2010 judgment of a three-Judge Bench of the Allahabad High Court delivered in a batch of title suits over the then-disputed land in Ayodhya. The PoW Act, on the other hand, is a statute designed to “prohibit conversion of any place of worship and to provide for the maintenance of the religious character of any place of worship as it existed on the 15th day of August, 1947…”. Pertinently, Section 5 of the said Act expressly exempts the legal proceedings in relation to Shri Ramjanmabhoomi from the application of the Act. This is recognised by the Supreme Court itself in Paragraph 80 of the Ayodhya judgment.

In light of this, there was no need for the court to discuss the Act in the context of Shri Ramjanmabhoomi. And yet, the court deemed it fit to discuss the Act in over 10 pages, with the central thrust of its deliberation being “the Constitution’s commitment to secularism”. The stated reason for this discussion is captured in Paragraph 84 of the judgment. In the said paragraph, the court reproduced what it believed were the “observations” of Justice D V Sharma, who was part of the majority opinion delivered in the case by the Allahabad High Court. Extracted below are the “observations” of Justice Sharma that ostensibly triggered the Supreme Court’s discussion on the PoW Act:“1(c). Section 9 is very wide. In absence of any ecclesiastical Courts any religious dispute is cognisable, except in very rare cases where the declaration sought may be what constitutes religious rite. Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991 does not debar those cases where declaration is sought for a period prior to the Act came into force or for enforcement of right which was recognised before coming into force of the Act.”

To verify whether the above extracted portion was indeed part of Justice Sharma’s “observations”, this author perused his opinions in the 2010 judgment, which are available on a dedicated public portal created by the Allahabad HC for its verdict in the case. The perusal revealed that the portion reproduced by the SC as Justice Sharma’s “observations” are to be found in his 1,130-page judgment in O.O.S.No.4 of 1989 titled The Sunni Central Board of Waqfs U.P., Lucknow & others Vs. Gopal Singh Visharad & others.

However, what was startling was that the said portion was not part of his “observations”. In fact, it was an extract from an earlier Supreme Court judgment that Justice Sharma had relied upon and reproduced as case law on the scope of civil suits under Section 9 of the Civil Procedure Code (CPC). This is evident from Page 121 in Volume 4 of Justice Sharma’s judgment, wherein he examined whether the fundamental rights of a community under Article 25 to protect and preserve the core of its faith may be enforced through civil suits under Section 9 of the CPC. He answered this question in the affirmative and held as follows:“The fact that Ram Janambhumi is an integral part of Hindu Religion and the right to worship there is a fundamental right of the Hindu religion and can be enforced through a suit can be clearly made out through a number of decisions of the Hon’ble Supreme Court.”

It is in the above context that Justice Sharma cited several judgments of the Supreme Court, one of which was Most Rev. P.M.A. Metropolitan & Others Vs. Moran Mar Marthoma & Another, delivered by the apex court in 1995. Justice Sharma specifically extracted Paragraphs 43 and 89(1)(c) of the said 1995 judgment, and it is the latter paragraph that the Constitution Bench in the Ayodhya verdict has erroneously construed as Paragraph “1(c)” of Justice Sharma’s “observations”.

Importantly, not only was the Constitution Bench’s attribution of the said portion to Justice Sharma factually erroneous, the context attributed to the said portion too was incorrect. This is because the thrust of Justice Sharma’s reliance on the 1995 judgment was in relation to the use of civil suits for enforcement of fundamental rights under Article 25. It was evidently not a discussion on the PoW Act in relation to the Shri Ramjanmabhoomi case. This being so, can the Constitution Bench’s discussion on the PoW Act in the Ayodhya judgment be treated as law of the land under Article 141 of the Constitution?

Given the non-application of the PoW Act, and hence its irrelevance to the Shri Ramjanmabhoomi case, the observations of the Constitution Bench must necessarily be treated as not legally binding. This conclusion draws support from the dicta of the SC in Jagdish Lal v. State of Haryana (1997), Director of Settlements, A.P. & Ors vs M.R. Apparao & Anr (2002) and other judgments. In the said judgments, the Court held that only those of its adjudicatory observations in a given judgment, which related to issues that arose for its consideration in a given case, would have a legally binding character under Article 141.

Applying the above principle to the Constitution Bench’s discussion on the PoW Act in the Ayodhya verdict, since it was neither relevant for adjudication of the title dispute in the facts of the said case, nor would its absence have made a difference to the outcome in any manner, the discussion does not acquire a legally binding character under Article 141.

J Sai Deepak

Advocate practising before the Supreme Court of India and the Delhi High Court

(Email: jsaideepak@gmail.com)