On March 6, a Supreme Court Bench consisting of Justices A M Khanwilkar and Dinesh Maheshwari declined to entertain a plea seeking guidelines for registration of criminal cases for sedition. The petition made a specific reference to an incident in Karnataka where a sedition case was framed against a few in charge of a school for staging a play. Many such cases have been filed across the country in recent times. Some of them relate to putting up banners or raising political slogans.

Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) deals with the offence of sedition. It is a colonial provision. By virtue of Article 372 of the Constitution it continued to govern the citizens of India, as it was not repealed. Its misuse has been rampant. Its history is curious. Prior to Independence, it was invoked against Gandhi, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, Aurobindo, Annie Besant and Abul Kalam Azad, among others. In the ‘great trial’ of 1922, Gandhiji said about the legal provision: “I know that some of the most loved of India’s patriots have been convicted under it. I consider it to be a privilege, therefore, to be charged under that section.” Though Nehru criticised the provision as “highly objectionable and obnoxious”, at no point of time did the Congress-led Centre think of repealing it. During unjust political situations, illiberal regimes misused the law against their own citizens and the saga continues even now.

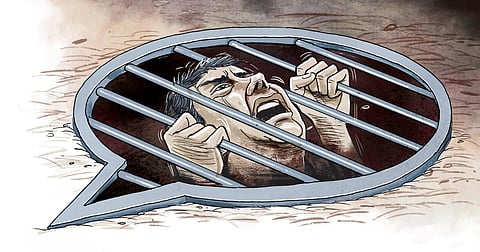

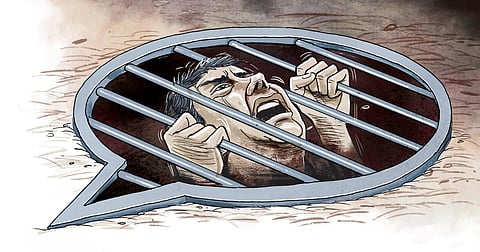

According to the provision, words or signs or visible representations that bring in hatred or contempt towards the government amount to the offence of sedition. The maximum punishment is imprisonment for life. So the law’s very vocabulary has a draconian effect, as it indicates that even a criticism of the government could be branded as seditious. The provision, on the face of it, is intimidating and undemocratic.

However, in Kedar Nath Singh (1962), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the provision with a significant rider that “comments, however strongly worded, expressing disapprobation of actions of the government, without exciting those feelings which generate the inclination to cause public disorder by acts of violence, would not be penal”.

The court emphasised that even a stringent criticism, written or spoken, “will be outside the scope of the section”. The accused in that case was a leader of the Forward Communist Party, who spoke about “revolution” that would establish “a government of the poor and the downtrodden in India”. In Balwant Singh (1995), the top court said that a casual raising of a slogan like “Khalistan Zindabad”, without any other act, cannot attract the charge of sedition. Bilal Ahmed Kaloo (1997) said that existence of an overt act is the decisive ingredient of the offence.

The emerging legal position is that when there is no incitement to violence, there is no offence of sedition. Certain statements or remarks by themselves cannot make out an offence unless they “create disorder or have the pernicious tendency to create public disorder”, to use the phrase in Kedar Nath.

This writer has argued even earlier that the provision as such had to be scrapped by the top court or repealed by the legislature. There is an ostensible ambivalence in Kedar Nath, as it abundantly warns against the dangers of textual reading and motivated invocation of the provision by the police or the government of the day.

The judgment relied on the British genesis of the sedition law, whereas even in Britain, the law was abolished in 2010, as it was found unsustainable in the light of the Human Rights Act, 1998. In countries like New Zealand, the US, Canada and Australia, sedition law has either been abolished or put to disuse. In Nigeria, the provision was judicially struck down in Arthur Nwankwo (1985) . The Indian law on sedition is also dangerously overbroad and capable of “trapping the innocent” and so vulnerable to constitutional scrutiny. Again, other provisions in the penal code dealing with offences against the state are adequate to achieve the object of protection of sovereignty. Sections 121, 121A and 122 of the IPC deal with the offence of waging war against the government of India. And there are special enactments to deal with terrorism and other anti-national activities.

As such, the provision is a dangerous and risky addition, even from the state’s point of view. Reports say that 48 cases of sedition were registered in 2014 and the number rose to 70 in 2018. There is reason to think that the trend got further accelerated thereafter. During the four years since 2015, though 191 cases for sedition were filed, trials were concluded only in 43 among them, leading to only four convictions. This revelation by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) is testimony to the law’s humiliating track record. During the UPA regime, in 2011, hundreds of activists who protested against the nuclear power plant at Kudankulam were booked for sedition.

In the famous decision in Texas v Johnson (1989), the US Supreme Court said that even the right to burn the US national flag falls within the ambit of free speech, for, in the words of Justice Anthony Kennedy, “it is poignant but fundamental that the flag protects those who hold it in contempt”. India, on the other hand, requires a minimum guarantee that those who are on the streets, saluting the national flag and holding the Constitution in their hands are not labelled as culprits. Mark Twain has put it in perspective: “Loyalty to the country always; loyalty to the government, when it deserves it.”

KALEESWARAM RAJ

Lawyer, Supreme Court of India Email: kaleeswaramraj@gmail.com