In the last couple of months, we have heard a lot of talk happening around substance abuse among stars and starlets in Mumbai, Bengaluru and elsewhere. People have been hounded, put through the grind of enquiries, and also formally charged by the Narcotics Control Bureau for either consumption of drugs or the peddling of them.

What became central to this drugs debate was a manipulated righteousness around the idea of chemical and psychological addiction that caused the ruin of reality. That is, the creation of utopias and dystopias, and the artificial inducement of highs and lows. The establishment is obsessed with only a certain kind of addiction while there are several others that are potentially as harmful. They are not placed in the problem category because they drive several important things and most of all a formal economy.

The demand-supply game is constantly kept going here. In a way, prices, inflation and stock markets are all about successfully generating addictions, which we seldom speak about or are blissfully unaware of. We speak about the economy too in the exact terminology of psychotropic substances, that is ‘surges’, ‘stimulus’ and ‘depression’.

The other debate we have had in the recent weeks—the fudging of television rating points (TRPs)—looked like a continuation of a discussion thread on drugs, because this too was about manufacturing addictions through inducements for a particular brand of news. Although this scam seemed borrowed from the industrial age when we are actually into the age of algorithmic addiction. ‘Social Dilemma’, a documentary that was an October trend on Netflix, drove this home as we sat at the edge of our seats.

A chapter excerpted from a soon-to-be published book by British author Jeremy Seabrook, on climate change and its inner landscapes, had these powerful lines on the nature of the beast: “Addiction is abasement and dependency, thraldom and obsession—whether to drugs, gambling, spending, mobility, sex, consolation, escape, entertainment or any other distraction to be procured by money, itself the most addictive substance known to humanity…

Addiction is an intelligible and efficient response to a world made unintelligible by continuous economic, technological and social change. It is no aberrant condition, but expresses something essential about the nature of the ‘freedoms’ which overwhelm us.” To pick up from the last line about ‘freedoms’, it is quite revealing as to how internet platforms and tools that were advertised as offering greater freedoms and deeper democracy have today become entwined with dangerous shades of addiction and a totalitarian impulse to keep the world unintelligible.

They have flattened the landscape and sowed the seeds of false equivalences to such an extent that even society’s crude binary construct of ‘right and wrong’ have been challenged. Through their algorithms and filter bubbles, they have created echo chambers where there is only one opinion and one enemy.

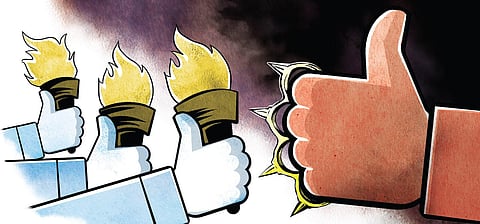

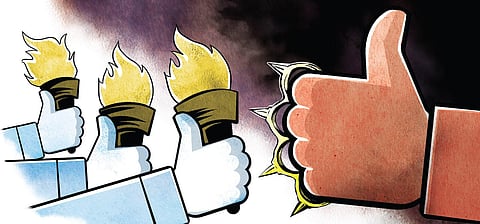

It is surprising that only a decade ago, when Tunisia saw the ‘Jasmine Revolution’, and ‘Arab Spring’ followed, social media was pushed as a liberating platform that was unshackling people from oppressive regimes. Many headlines in the Western press were euphoric assertions like ‘How an Egyptian Revolution Began on Facebook’.

As users and profits for social media corporations grew, and the mythology of the freedoms they nurtured were dismantled, the narrative about their addictions began to gain ground in the ‘free world’. Forget who replaced the long-in-office dictators in dictatorships, the benefits that ironically accrued to the free world from these platforms were unmissable: There was a Donald Trump in 2016. Around the time, addictions for hate, abuse and flat societies had been perfected on social media.

Interestingly, popular leaders like Trump, whom the mainstream media did not cavort with, started directly communicating to their audiences on social media. And once that strategy was in place, they either brought more of their audiences to the platforms or created robust opinion fences around those who already existed there. It is in those enclosures that a lot of things that we are slowly becoming familiar with were harvested. Part of this plan was to discredit mainstream media as elite and fake.

In the last few months, we are witnessing new protests outside the clutches of social media in Belarus, Poland, Sudan, Chile and Nigeria among other countries, and the fight now is to stop the abuse of democracies. If drugs created delusion and dystopia, algorithms became the new drivers of dopamine and ‘commodification of human attention’. In India too, this project that picked up speed around 2011 is now at the crossroads with the resignation of Facebook senior public policy staffer Ankhi Das, who had become controversial for her alignment with the BJP.

But as Time magazine pointed out, her interim replacement is another person who helped the BJP campaign in 2014. Social media is neutral to the extent that it creates similar frustrations in opposite camps: the right and the liberal. Its unmediated aim may be to put both ideological groups at the mercy of approval gangs on the platforms. Their addiction would push them to not only conform to seek approval, but to keep up when the bar of conformity is raised.

If you are from the right or a liberal, you are expected to travel to the extremes each minute to gain likes, shares, retweets and friends. You are pushed to scout new invectives for Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi to remain members of addictive communities. This would only make everyone a reactionary. To break away from this destructive cycle, which incrementally shrinks reflection and self-worth, is the biggest challenge before us.

Sugata Srinivasaraju

Senior journalist and author (sugataraju@gmail.com)