The last week of September saw a flurry of activity with senior officials of the Quad meeting virtually to look at potential areas of convergence in a post-Covid world. As a preliminary discussion prior to the second Quad foreign ministers meet scheduled to take place in Japan on October 6, the virtual meeting aimed to address core areas of concern among members. Interestingly, as far as the processes of multilateralism are concerned, the Quad meeting once again reiterated its support for the centrality of ASEAN and ASEAN-led mechanisms in the region. This brings the focus well and truly on regional transitions in the Indo-Pacific, even as the pandemic has unleashed economic uncertainties and geopolitical challenges.

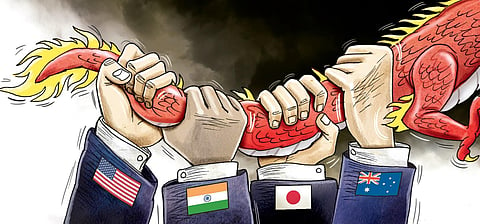

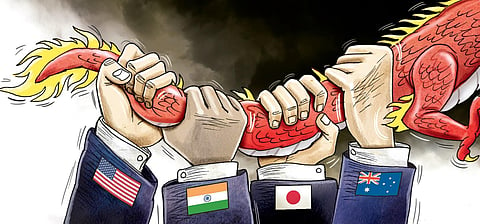

A core outcome of the meeting was highlighted by the statement of the Ministry of External Affairs on the relevance of a “free, open, prosperous and inclusive” Indo-Pacific where countries furthered their “shared values and respect for international law”. Increasingly, the reference to shared values and respect for international law has implicitly addressed growing concerns among states over Chinese aggression and efforts to shift the regional balance in its favour. Even during the height of the pandemic, Chinese behaviour has reflected little respect for the international community and international law. Rather, it almost seems as if China is using the preoccupation of countries with the pandemic to increase its belligerence in a bid for regional and global status.

A little over a year ago, there were growing concerns as to the sustainability of the Quad as a means of supporting the rules-based approach in the wider Indo-Pacific. Two countries that clearly stood apart from within the Quad were Australia and India, who shied away from an outright commitment to the group given the importance of their bilateral engagements with China. A speech by the Australian Defence Minister Christopher Pyne in Singapore in January 2019 made it clear that Australia was keen to avoid the implications of another ‘Cold War’ in the region, this time propelled by US-China rivalry.

This statement came in the aftermath of the 2017 United States National Security Strategy paper that clearly identified China as a competitor to “American power, influence and interests”. For Australia, economic relations with China was another factor that compelled it to balance ties between Washington and Beijing. Australia is China’s sixth largest trading partner; China is the largest trading partner for Australia both in goods and services. However, in the aftermath of Covid-19, bilateral ties between the two have been strained, particularly in light of Australia supporting the idea of an independent inquiry into the origins of the pandemic. The lowest point of the ties was when Chinese state media referred to Australia as a “dog of the United States”.

Similarly, India too did not initially embrace the Quad fully, given that it had a ‘China containment’ view. Even in the aftermath of the Doklam crisis in 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in his speech at the Shangri La dialogue of 2018, reiterated the importance of an “inclusive” Indo-Pacific, significantly pushing the onus on a collective model of accommodation of interests and concerns. Furthermore, in an effort to address the bilateral tensions with China, the informal summits of Wuhan and Mamallapuram were high in optics while yielding minimal outcomes. The current border tensions in Ladakh add greater complications at the bilateral level, pushing India to further consolidate its own interests with like-minded states.

While several observers have viewed the exit of Shinzo Abe from the political scene as likely to have a serious impact, this may not be the case. Japan’s commitment to the primacy of its special security relations with the US will remain in place. Moreover, the question of Japan becoming a ‘normal’ state was in discussion prior to PM Abe’s leadership. Critical to this assessment is the July 2014 reinterpretation of the right of maintaining the Japanese Self Defence Force, which can now support and fight with its allies in defence of itself and larger allied interests. This shift will remain in place in the post-Abe period and will continue to bring Japan into closer integration with other states to maintain a rules-based order.

One of the core issues is the effort to address the stability of regional and global supply chains that are affected by the pandemic. China holds primary importance as the leading player in global supply chains. On 1 September 2020, three countries among the Quad, Australia, India and Japan, set up the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative to look at options to diversify the uninterrupted movement of goods. This will be a focus of the foreign ministers meeting on 6 October 2020 at Tokyo. The meeting is also expected to look at a post-Covid global order and the challenges that will emerge from it. Even as the US is grappling with a mounting death toll due to the pandemic, has its President in hospital with Covid-19 and prepares for a bitterly contested election next month, the challenge of maintaining its primacy will remain critical. The logic of direct proportionality implies that a rise in Chinese belligerence will see a proportional rise of the Quad.

Shankari Sundararaman

Professor, School of International Studies, JNU, New Delhi

(shankari@mail.jnu.ac.in)