Even as Ladakh remains strongly etched in the public mind as an area of major concern in the security domain, there is much interest in the state of things in J&K. The enormous complexity of the problem is, however, not fully perceived by most, although the situation being currently ‘advantage India’ is largely appreciated. The need for full narrative control to enable the correct perception to prevail and allow the rightful progression of the situation flowing from the historic decisions of 5 August 2019 is a virtual imperative. Narrative control is something that India has taken for granted in the past, laying little focus on it due to a self-perceived belief that we have moral dominance.

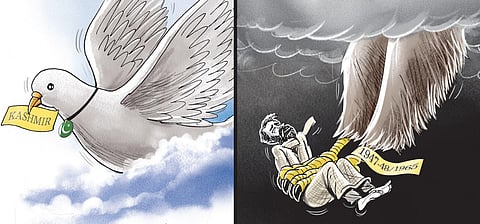

That is a good abiding belief but in the world of realpolitik, what is also important is to cultivate that belief in the international community: the people, media and leadership. Making our narrative their narrative remains the key. An event organised at Srinagar’s Sher-e-Kashmir International Convention Centre by India’s Ministry of Culture on 22-23 October 2020 to commemorate 22 October 1947 as Black Day for the first time is an appropriate beginning in this direction.

It’s surprising how little is known to people about the crucial period 22-27 October 1947, a time that defined the destiny of J&K. The progression of events from then to various important historical milestones in Indo-Pakistan relations has also never been highlighted enough for our own people to take note and speak about. It is thus the Pakistani narrative that has prevailed internationally and within J&K, of the Hindu ruler being influenced under coercion to opt for India even when the majority population was Muslim.

That narrative also speaks of India’s unilateral military action to annex J&K, non-adherence to the UN resolutions and continued abrogation of the rights of the people of J&K. I found this perception prevailing among the people and media in many countries I visited after 5 August 2019 even as the governments there backed India’s decisions. 22 October 1947 is symbolic of the larger intent of Pakistan, which was prevalent well before the final decision to partition India. Pakistan had perceived the problem likely to arise relative to J&K; the strategic location, its water resources and Muslim population being the issues.

It was fully aware that once Partition had been executed, it would take time for the Pakistan Army to come into being through division of the British Indian Army, thus offsetting the possibility of effective military intervention. Pakistan’s Maj Gen Akbar Khan, in his book ‘Raiders in Kashmir’, explains in sufficient detail the actions taken clandestinely to equip an irregular force to invade J&K and prevent India from responding effectively. It is unclear as to how the decision to harness the frontier tribesmen or ‘kabbalis’ was taken—perhaps through some ex-servicemen tribal leaders.

Pakistan also had no intention of abiding by the Stand Still Agreement with the Maharaja and continued seeking ways to coerce him, including placing a blockade on access to Srinagar. Akbar Khan meanwhile directed raids all across the borders of J&K to create communal tension. The date for commencement of the main offensive, termed Operation Gulmarg, was 22 October 1947 in order to have sufficient time to stabilise before the winter, which would anyway act as a deterrent for any delayed Indian counter action.

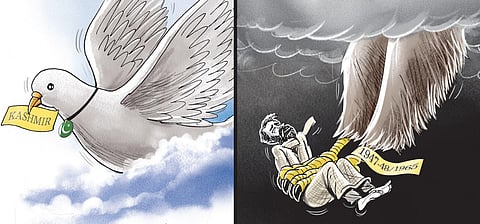

The tribesmen of the North West Frontier were selected to undertake the bulk of initial operations and organised into ‘lashkars’ of 500-1,000 men; the intent here was deniability of any official Pakistan hand. Two major characteristics of later-day Pakistani doctrine appeared to have its origins here. Effective and credible denial backed by professional information handling became a way of life and an indelible part of Pakistan’s strategic doctrine.

The second was the employment of irregulars to execute the bulk of operations with the Pakistan Army in support. Despite the severe mauling that the ‘kabbalis’ received at the hands of the Indian Army in 1947 and the terrible reputation they obtained due to the pillage, plunder and rape they indulged in Baramulla and other places, the Pakistan Army continued to believe strongly in the power of the irregulars to deliver. In 1965, it attempted the same strategy with Operation Gibraltar in the hope of engineering an uprising of the Kashmiris.

The hope vanished soon when the Kashmiris, like in 1947-48, came to the support of the Indian forces. Since 1989, Pakistan has relied on similar strategies applied in a variety of ways and used information spin to seek advantage. The lessons that emerged from the 1947-48 experience also taught Pakistan the necessity to have a dedicated body to handle information spin; the Inter Services Public Relations (ISPR) agency was thus created in 1949, predating the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI).

It is through information spin that Pakistan has attempted to convince the world of the J&K people’s resentment against India. Therefore, historic instances such as the resistance to the Pakistani raiders by the people of Kashmir in 1947-48 and 1965 need to be retold the Indian way. The stories of individual valour of great Kashmiri nationalists such as Maqbool Sherwani and Master Abdul Aziz of Baramulla, who were summarily executed by the marauding tribals, also need to be better documented.

That the tribals carried away innumerable women after killing their families has hardly been known to people in India, let alone the world. Pakistan’s use of foreign jihadi mercenaries in the nineties, their misdemeanours against the people, especially women, also needs to be highlighted in various counter narratives. There is little recorded information on these sordid events for today’s world to take cognisance of.

Lastly, the UN resolutions on which Pakistan places great emphasis in its pleadings to the world need to be brought into the right perspective. India’s information blitzkrieg, hopefully in the making, must include the basics that it was Pakistan that failed to adhere to the requirement of withdrawal of its forces in order for India to initiate the process of plebiscite under UN aegis. The Instrument of Accession being the legal document in favour of India gave it that right.

It must thereafter focus on the Shimla Agreement of 1972 to which Pakistan is a signatory and which effectively overrides the UN Resolution and makes plebiscite irrelevant. Pakistan continues to ignore the Shimla Agreement and focuses on rekindling the irrelevant UN Resolutions that have been overtaken by history. In that it finds succour in painting India black, a stance that needs effective countering over time by our own narrative control. By calling 22 October 1947 Black Day, a good beginning has been made but clearly much more needs to be done.

Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain (Retd)

Former Commander, Srinagar-based 15 Corps. Now Chancellor, Central University of Kashmir

(atahasnain@gmail.com)