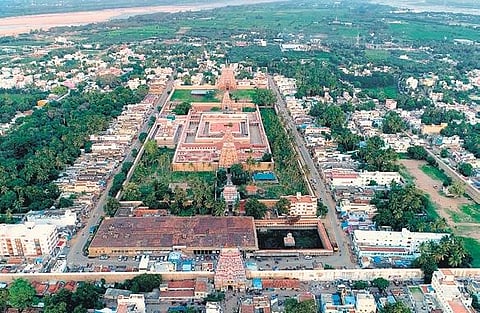

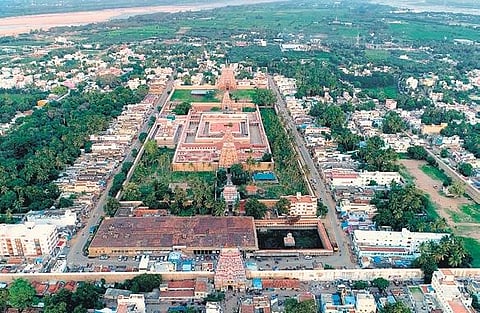

Tiruvanaikka, a quiet town near Tiruchy with a massive temple complex and broad and aligned streets that resonate with sacred chants, is one of the pancha bhootha shrines of Shiva in South India. This temple, which has been active since the 5th century CE, shares the island of Srirangam with the famous temple for Ranganathaswamy, a form of Vishnu. Sanctified by the Thevaram hymns, the Tiruvanaikka temple is unique in several ways.

The temple walls echo the sound of inscriptions being chiselled to record information, royal orders, commands of officials and sometimes even the words of the Almighty. The oldest inscription found till now is an early Chola inscription of Parantaka I (10th century CE); there are more from the later Cholas, later Pandyas, Hoysalas, Rashtrakutas, Vijayanagara and Nayak kings. The knowledge corpus these equip us with is immense. For example, the temple houses a fragmentary inscription of Parantaka I that addresses him as Maduraikonda Parakesari and mentions his endowment to burn a perpetual lamp to the Mahadeva Bhattarar or Shiva as he was called then. Only very few inscriptions of Parantaka I have ever been documented, so this one is worth its weight in gold!

Following Parantaka, several inscriptions recording the long list of gifts, jewellery and land donations made by the medieval and later Chola monarchs are sprinkled all around the temple. However, Tiruvanaikka also has a few inscriptions that paint us a clear picture of the shift in political power from the great Cholas, whose might was almost history by the 13th century, to their subordinates like Kopperunchingan, the Kadava king. It is around the same time when the already popular Hoysala dynasty was expanding its territories. From the times of Rajaraja III, the Chola empire faced severe political turbulence and the rulers had to depend on the Hoysalas for their own safety. Due to its proximity to Kannanur, the second Hoysala capital, the Tiruvanaikka temple has a few inscriptions that reflect the Chola-Hoysala relationship.

An often unnoticed shrine built during this period is the Somaleshwaram shrine housing an image of Shiva and Parvati. Two almost defaced inscriptions, partly in Kannada and partly in Grantha, record the structure being built by Vira Someshwara, the Hoysala king, in honour of his queen Somala Devi. Though small, the Dwarapalakas and Nandi icons seen here reverberate with the Hoysala finesse. Several inscriptions of Tiruvanaikka record the importance Vira Someshwara had in the development of the temple and his able administration.

River Kaveri garlands the island of Srirangam and a heavy monsoon often floods the settlements. Sometimes the gushing flood water even washes away boundary stones that demarcate the extent of individual lands. One inscription documents such an incident that happened in the times of Kulottunga Chola III, when a committee with representations from both the temples of Srirangam and Tiruvanaikka, along with government officials, measured the extent of the temple lands as per existing records and relaid the boundary.

The Tiruvanaikka temple since the 13th century CE has been a strong spiritual centre around which many religious institutions and monasteries functioned. Several inscriptions tell us that these institutions, despite following different branches of Shaivite philosophy, coexisted in close proximity to the temple. Narpattenaayiravar Mutt, Andar Embiran Mutt, Sangama Devar Mutt, Somanatha Devar Mutt and Akhilandanayaki Mutt are a few of the institutions that functioned here. Going by the names and descriptions of their traditions, one can be sure that these mutts propagated different branches of Shaivam, namely—Pasupata, Siddhanta Saiva and Virasaiva. One such continuous tradition bestows the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetam, administered by the Shankaracharayas, with the privilege of performing the tatanka pradishtai, the ceremonial offering of the highly ornate and unique earrings to Tiruvanaikka’s Goddess Akhilandeshwari.

It was a general tradition in the Chola period to address inscriptions of Shiva temples in the name of Adi Chandeshwara. The deity is in fact described as the senior attendant and caretaker of the temple. Among several such orders is an interesting one made in 1585 CE about the appointment of a certain Chandrasekhara Guru Udaiyar as the temple high administrative officer. The inscription starts by quoting the erstwhile tradition of selecting a disciple of a Pasupata sanyasi (a pontiff) for this post, command of which extended into general administration, accounts and associated power, checking on traditions and deciding on privileges for other temple employees.

However, with the appointment of Chandrasekhara Guru, the tradition shifts from appointing a sanyasi to a gruhasta (a householder). What makes it more interesting is that the representatives are expected to observe pasupata vratam; the inscription says Chandrasekhara Guru and his descendants shall now observe gruhasta pasupata vratam. The shift of administrative control from a pontiff to a householder and bestowing the rights directly to his descendants was a revolutionary change. How this was accepted by the other temple employees and devotees remain unanswered due to paucity of data.

These are less than a handful of examples from close to 200 inscriptions documented so far in the Tiruvanaikka temple. If that can give us such diverse information on events ranging from flooding to finance, burning a lamp to fall of a dynasty, different schools of philosophy to change in administration control, imagine how much our temples have in store to share with us! Unexplored areas like the role of Hoysalas in the Tiruvanaikka temple need to be studied in detail for a deeper understanding of our history. They are truly embedded layers of history, waiting to be deciphered.

Madhusudhanan Kalaichelvan

Architect, serves on the govt-instituted panel for conservation of temples in TN

(madhu.kalai0324@gmail.com)