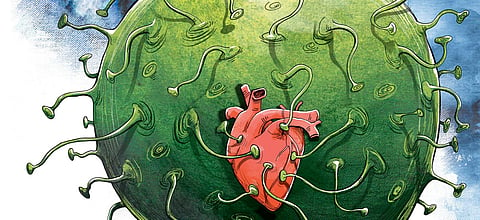

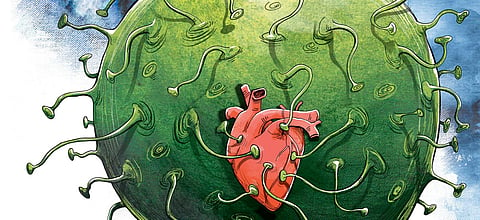

Like the mythical Cupid’s arrow, the very real Covid virus seems to aim for the heart as it flies towards you through the air. The ‘respiratory’ virus is not confined to the nose, throat and lungs that form the initial landing bay. It spreads soon thereafter via the blood vessels to reach different parts of the body. The heart, brain, pancreas and kidneys are among the many organs to be affected as the virus reaches every part of the body, with varied clinical manifestations and poor outcomes in those who are affected badly.

The initial attention was on respiratory effects like dry cough, viral pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). These effects were seen to be similar to, but less lethal than, the Serious Acute Respiratory Infection Syndrome of SARS-1 virus. Hence the name SARS-CoV-2 conferred on the new virus. The effects of the virus on the heart and blood vessels were recognised as the pandemic progressed, with autopsy evidence from Italy initially highlighting the extensive thrombosis or blood clotting along the blood vessels of the body. The recognition of ‘myocarditis’ or inflammation of the heart muscle came soon thereafter.

That there is injury to the heart was evident from the elevation of the blood levels of various enzymes and other chemical markers that are derived from the heart muscle or in response to cardiac muscle dysfunction. The question was whether this is a direct effect of the virus or a result of the immunologically mediated inflammation that arises in response to viral infection. That would have a bearing on the treatment, in deciding whether anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive drugs would be beneficial or if antiviral drugs need to be used to target the virus itself.

Initially, it was assumed to be an effect of the body’s immunological response going into overdrive, harming the heart muscle with toxic chemicals that are primarily intended to destroy the virus but surge to high levels in the circulating blood. Lung damage due to viral infection can also place stress on the heart, as do large blood clots that compromise blood circulation through the lungs. Falling blood oxygen levels themselves can cause heart muscle dysfunction. Blood clots in the coronary arteries, which supply the heart with blood, can lead to heart attacks. Thus, the cardiac problem was perceived to be a secondary phenomenon due to immunological injury or mechanical factors impeding blood circulation to the lungs or the heart.

ALSO READ | A covidful of confusion and corrections

However, recent evidence has emerged of direct viral assault on the heart muscle. Scientists at the San Francisco-based Gladstone Institutes attempted to study the effect of the virus on heart muscle fibres, independent of other factors that may cause heart muscle dysfunction. They added the SARS-CoV-2 virus to human heart cells grown in lab culture dishes. They were shocked to see the virus cleanly cut the heart muscle fibres (cardiomyocytes) into small bits. They said this type of dicing was unlike anything they had observed before in any other disease affecting the heart. There were also black holes in the nucleus of heart muscle cells where the DNA should have been, with the appearance of empty shells. Other human heart cells (cardiac fibroblasts and endothelial cells) were unaffected. Autopsy specimens of hearts from patients who died of Covid-19 also showed similar findings of ‘cardiac muscle fibre carnage’. Earlier, a cardiac MRI study in Germany showed evidence of heart muscle damage in relatively young people who had mild disease and whose average age was 49 years.

This evidence of direct heart muscle damage by the virus is worrisome in terms of long-term effects and may explain the prolonged fatigue and low exercise capacity in many persons who have been clinically declared to have recovered from Covid-19. It raises the question of considering Covid-19 a chronic disease, rather than an acute infection that is transient in its effects on many in the population. Unfortunately, the heart does not have regenerative capacity like the liver. Will the islands of damage to the heart muscle, even if asymptomatic now, lead to problems when people move into old age? We do not know, but the question does argue for caution even among the young and middle aged who consider themselves protected from the debilitating effects of the virus.

The relationship of pre-existing heart disease and high blood pressure to increased risk of experiencing severe disease or dying of Covid-19 is well established from reports of the pandemic from different countries. That poses the immediate threat. Whether fresh heart muscle damage caused by the virus itself aggravates cardiac dysfunction in persons with pre-existing disease or creates long-lasting cardiac disease in others who previously had healthy hearts needs to be examined. Either way, it is likely to be a contributory factor to adverse clinical outcomes. The message to protect one’s heart from the SARS CoV-2 virus, whether previously diseased or pristine, comes as a clear one as we all observe the World Heart Day (WHD) on September 29. It is timely that the World Heart Federation, which initiated WHD along with the WHO, has recently initiated a large global study on the cardiovascular effects of Covid-19.

(Dr Srinath Reddy is a cardiologist, epidemiologist and the President, Public Health Foundation of India. He is also the author of Make Health in India: Reaching a Billion Plus. He can be reached at ksrinath.reddy@phfi.org. Views are personal)