In a highly commendable move, the Rajapaksa brothers, who hold the reins of power in Sri Lanka, invited the UN Human Rights Council dealing with contemporary forms of slavery to visit Sri Lanka, study the living conditions of the most exploited sections of society like people working in garment firms in export promotion zones, tea plantation workers and migrants. Sri Lanka is the first country in South Asia to take this imaginative initiative. Will other countries in the region emulate the Sri Lankan example?

Tomoya Obokata, UN Special Rapporteur, visited Sri Lanka between November 26 and December 3 for an on-the-spot study of the problems and met a cross section of workers, government officials, trade union leaders and NGOs involved in the subject. The rapporteur presented the preliminary findings in a meeting held on November 26. The final report would be submitted to the UN in September 2022.

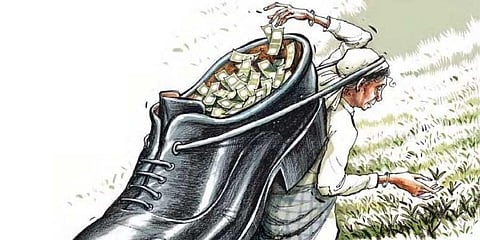

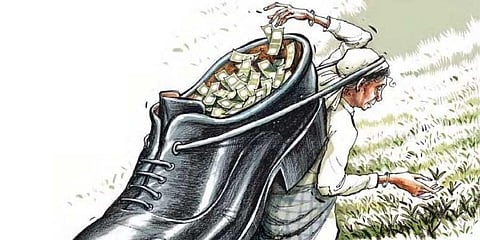

The workers in the tea plantations are of Indian Tamil origin. Apply any yardstick—per capita income, living conditions, longevity of life, educational attainments and status of women—they are at the bottom of the ladder. The UN Special Rapporteur has highlighted: “Contemporary forms of slavery have an ethnic dimension. In particular, Malaiyaha Tamils—who were brought from India to work in the plantation sector 200 years ago—continue to face multiple forms of discrimination based on their origin.”

In 2017, Sri Lanka celebrated the 150th anniversary of its tea industry. The government and the planters organised a number of seminars and conferences to highlight the role of the tea industry in the economy, how to increase production in the sector and how to modernise it. The Institute of Social Development in Kandy was the only organisation that convened a seminar on those who produce the Two leaves and a Bud (novel written by Dr Mulk Raj Anand) that brings cheer early in the morning to millions across the world.

The contrasting lives of the planters and workers should be highlighted. Given below are two quotations that describe the contrast. The BBC, in 2005, telecast a documentary titled How the British Reinvented Slavery. The documentary portrays the lives of the planters as follows: “You can sit in your veranda, and sip the lemonade and be fanned by a servant and have your toenails cut at the same time by some coolie, and you can watch your labourers working, you could sleep with any woman you wanted, more or less everything was done for you from the time you wake up and the time you went to bed. People looked after you, people obeyed you, people are afraid of you, your single word as a plantation owner could deny life.”

Vanachirahu, a young poet from Malaiyaham, gave expression to the innermost feelings of his people in times of communal troubles. In a poem titled Dawn, the poet writes: “Our nights are uncertain, dear, let us look at each other, before we go to bed. This may be our last meaningful moment. Finally press your lips on the cheeks of our children. Then let us think about our relatives for a moment. Lastly let us wipe our own tears.”

The most important feature of the Malaiyaha Tamils is the sharp decline in their population. At the time of independence in 1948, they were more in number than Sri Lankan Tamils. Because of the two agreements signed in 1964 and 1974 between Colombo and New Delhi, and repatriation of a large number of people as Indian citizens, their number declined. Today, according to census statistics, they number only 5.5% of the population.

For the first few decades after independence, the major problem confronting the Indian Tamil population was the issue of statelessness. With a judicious mix of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary struggles, the community, under the leadership of Savumiamoorthy Thondaman, was able to extract citizenship rights from a recalcitrant Sinhalese-dominated government. All those born in Sri Lanka after October 1964 were granted citizenship, which also included the residue of the Sirimavo-Shastri pact, yet to be repatriated to India. With the introduction of the proportional system of representation under the 1978 Republican Constitution, the community was able to send more representatives to Parliament.

The community is now engaged in a struggle for equality and dignity. The living conditions are improving but much more remains to be done before they can enjoy the status of perfect equality. First and foremost, human rights violations continue to take place. Though the political parties representing the Malaiyaha Tamils never subscribed to the demand for a separate state, they were subjected to vicious and savage attacks by lumpen sections of Sinhalese in 1977, 1981 and 1983. I happened to be in Hatton after the Bindunewa massacre in 2006. Indira, a young lady, confided that she was scared to move around Hatton because of insecurity. She contrasted that to her life with her brother in Perambur, Chennai, where she could go without any fear for late-night film shows. Second, the tea workers’ daily wage is around 1,000 Sri Lankan rupees, which is not even sufficient to meet their daily needs. Many, therefore, absent themselves from the plantations and go to work in vegetable farms where they are able to get double the wages, in addition to breakfast and lunch. Finally, while every boy and girl goes to school, there are many dropouts. Very few enter the university level. I was associated with the University of Peradeniya as a SAARC Professor for International Relations in 2006. In the final-year BA class, in Tamil medium, there were 10 students, of whom eight were Muslim girls, a boy was from Batticaloa and a girl from the plantation area. In the same year, the number of teachers from the Indian Tamil community in the university was less than 10.

In his plan of action for three years, Sri Lankan High Commissioner Milinda Moragoda has highlighted that there should be more educational exchanges between the two countries. For instance, the Chennai Centre for Global Studies is very keen to step into the scene and assist the Tamil children, especially from the hill country, to come to India for secondary and college education, and is prepared to meet all their expenditures and also offer them scholarships. The community can come up only if they have good value-based education. Tamil Nadu can play a benign role in this direction.

The transformation from Thottakattan (barbarian from the plantations), a contemptuous term used by Jaffna Vellalars, to the noble appellation Malaiyaha Tamil is an illustration of the qualitative change that has taken place in the hill country. But much more remains to be done before they become equal citizens enjoying equality of opportunity.

Let me conclude with a poem written by M A Nuhman whom I had the privilege to know at the University of Peradeniya: “Where there is no equality, there is no peace, where there is no peace, there is no freedom, these are my last words, equality, peace and freedom.”

V Suryanarayan

Senior professor (retd), Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Madras

(The author was the Founding Director of the Centre in the University of Madras)

(suryageeth@gmail.com)