The Indian state has an ambivalent position in its relationship with the environment. The recent flash flood in the Rishi Ganga river in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand with its unprecedented intensity and virulence along with its human misery and ecological consequences has once again highlighted this fault. The economic growth model that thrives on compulsive consumerism and egregious global capitalism has admittedly no environmental sensitivity. Many countries have a well-articulated position vis-a-vis environmental concerns. For instance, the US does not have overt pretences about eco-sensitivity, though in Joe Biden’s presidency they have rejoined the Paris climate agreement.

On the other hand, Scandinavian countries and some European nations have a more sensitive and sensible environment policy. China is on the other extreme, with scant respect for environmental discipline. The Indian state, however, has a record of sorts in its hypocrisy on environmental issues. Successive governments at the Centre and state levels oscillate between environmentally encouraging words and ecologically devastating action. Governments have been generous with the green agenda as well as legislation and institutional arrangements for environmental justice.

We have the forest laws, green tribunals, wetland protection authorities, coastal protection agencies, Environment Impact Assessment rules, pollution control boards, regulations on quarrying and several such safeguards. A cursory look at the legislative and institutional bulwarks the Indian state has created to protect its environment is indeed formidable. Besides, there are high-profile, high-spending programmes like Namami Ganga meant to clean the Ganges. The Centre and state governments have several initiatives to prevent conversion of wetlands and encroachment of forestland, to limit construction in fragile zones and a number of similar initiatives.

However, several environment protection and reclamation projects, high- or low-profile, are essentially half-hearted attempts rather than concerted efforts prompted by conviction or commitment. Most of them are nothing more than photo ops for local leaders and enthusiasts. This fault line and staggering trust deficit are amplified when it comes to governments’ enthusiasm for mindless economic development. We have seen that none of the above safeguards really come in the way of promptly granting licenses for reckless quarrying of the forest lands of central India and Odisha. There are no qualms about clearing hydroelectric projects and new dams in the fragile Himalayan valleys. Environmental sensitivity is completely sidestepped for ambitious state-sponsored as well as private sector projects with the blessing of the government.

The widening of the road network connecting the Char Dham at phenomenal ecological costs and the massive Central Vista project are two such glaring instances. Governments in power decide on their pet projects and regulatory bodies mandated to critically and objectively examine and advise are often called upon (or intimidated) to say yes in chorus. The feeble voice of environment activists is drowned in the clamour of ‘national interest’ and the urgency of economic development. A typical instance is the Madhav Gadgil report that rightly highlighted the seminal value of the Western Ghats in conditioning the life, climate and sustainability of the regions lying to the west of Ghats (South Canara and Kerala). The scientifically tenable report was quickly vilified as regressive and impractical.

Even the subsequent watered-down version has not satisfied the pragmatists. The Himalayan ecology is far more fragile. There are several reports of experts warning against wayward intervention in the Himalayan ecosystem. Nonetheless, there is no dearth of dams, hydroelectric projects, construction and tourist circuits in that rarefied landscape. The spirited words of Jawaharlal Nehru while inaugurating the massive Bhakra Nangal dam in 1954, “Bhakra, the new temple of resurgent India, is the symbol of India’s progress”, are dated by the current understanding of dams and their deleterious impact. With his scientific temper, Nehru, were he alive today, would have been an ardent votary of environmental values and formulated a nuanced development paradigm for the country.

Environmental science was almost non-existent in the 50s. It is but natural that in the nascent glow of national freedom, the country desired a giant push in the form of major dams. However, today, after so much information, awareness and scientific proof of the impending disaster and global warming, it is highly myopic and irresponsible that we still go after reckless development like the rats and children behind the pied piper of Hamelin. The responses to ecological disasters cannot only be localised. For instance, if warming of the Himalayan zone is the cause of the glacier break that led to the flash floods in Rishi Ganga (the causes have not so far been officially confirmed), the solution is not a quick fix in the Himalayan region.

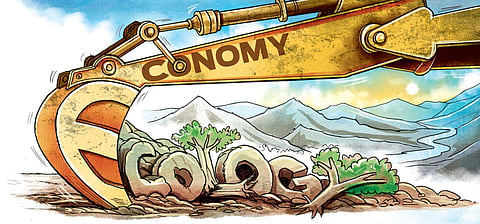

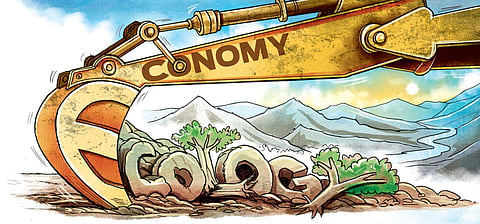

The whole country, nay, the whole world has to act in unison. The present tragedy is unfortunately not the last one the Himalayas would experience. The repeated warnings given by the mighty mountain have been callously ignored in our pursuit of more power, money and development. Unless every one of us starts chanting and practicing the alternative mantra ‘less of everything’, the avarice of consumerism will make us all vicariously liable for the ecocide waiting in store. We should rather enrich our lives with less consumption, extraction and demand on the environment. The lunge towards the $5 trillion economy could perhaps wait. The present disaster should make the Indian state unambiguously proclaim, ‘ecology first, economy next’. The tempting alternative, ‘economy first, ecology next’ is a sure prescription for catastrophe.

K Jayakumar (k.jayakumar123@gmail.com)

Former Kerala chief secretary & ex-VC, Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam Varsity