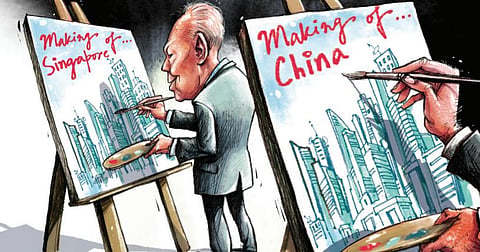

Lee Kuan Yew (1923–2015), the architect of modern Singapore, transformed the island republic “From Third World to First” (the title of his memoirs), an achievement unparalleled in modern Asian history. What is less known is the fact that this seminal figure was responsible for the transformation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). China today has become not only the foremost Asian power, it is rapidly catching up with the US.

Early in his political career, Lee realised that Singapore (a Chinese island in a Malay sea) could not afford to become a “Third China”. The leaders of Indonesia and Malaysia were concerned about Chinese cultural exclusiveness and their stranglehold on the economy. The nationalism had strong streaks of xenophobia, not only against the colonial powers but also against the economically powerful Chinese community. Addressing the Nanyang University in October 1959, Lee underlined: “If Nanyang becomes a symbol of Chinese excellence and the supremacy of Chinese scholarship and learning then verily we will aggravate the position of overseas Chinese.” It was this firm belief that made Singapore dissuade the “boat people” (mainly ethnic Chinese) from coming to its shores.

Adding to the complexity, the revolutionary leadership and militant following of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) came from the Chinese community. The MCP, which waged an armed struggle for power from 1948 to 1960, received powerful ideological and, to some extent, armed support from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The Malay leaders, therefore, were highly suspicious of China’s expansionist designs. This ethnic reality prompted Lee to declare that Singapore would be the last among ASEAN nations to establish diplomatic relations with Beijing, which it did only in 1990.

According to Lee, two major obstacles had to be overcome before normalcy was established in bilateral relations. After the Revolution in 1911, when Dr Sun Yat Sen became the President of Kuomintang China, he proclaimed a new Constitution under which citizenship went with ethnicity and not the place of residence. Thus a Chinese living in Malaya or Singapore became a citizen of China; his loyalty was to China and not to Malaya or Singapore. This policy made Southeast Asian nationalists view ethnic Chinese as Beiing’s “fifth column”. It was only after many years of persuasive diplomacy that China’s leaders revised their thinking. They advocated that the Chinese communities should become citizens of the countries in which they lived and began the universal practice of passports and visas.

The second impediment was the powerful ideological support that the CCP extended to fraternal communist parties. The Voice of Malayan Revolution, The Voice of Thai Revolution and The Voice of Burma Revolution—all underground radios—began to function from Southern China. The PRC, at that time, made a distinction between government-to-government and party-to-party relations. Lee, a staunch anti-communist in domestic politics, was referred to as a “running dog of American and British imperialism”.

Lee was able to convince the Chinese leaders that support to local communist parties was an obstacle if China wanted to expand economic and political relations. In a major initiative, China stopped the support to communist parties. Gradually China became a status quo power. During the Third Indo-China War, China worked together with the US and ASEAN to isolate Vietnam. The PRC has changed to such an extent that it is today the main supporter of many reactionary regimes—the military leadership in Pakistan, the Rajapaksas in Sri Lanka and the military junta in Myanmar.

It is worth narrating an incident that took place during the first goodwill visit of a Singapore delegation in 1967, which is given in S R Nathan’s book, An Unexpected Journey: Path to Presidency. The bilateral relations were still tentative. The centrepiece of the visit was the meeting of Lee and the Chinese Prime Minister Hua Guofeng. Hua presented Lee with a book, saying: “This is the correct account of the war between China and India. I hope you will find it useful.” Lee took the book, looked at the front cover, looked at the back, and said: “Prime Minister, this is your version of the war. There is another version, the Indian version. And in any case I am from Southeast Asia. It is nothing to do with us”. He handed the book back. Nathan has written, “For me, this was a very important moment, a clear confirmation that Lee Kuan Yew, ethnically Chinese, was his own man, in no way subordinate to China or the Chinese Communists.”

Another low point in China-Singapore relations deserves mention. Singapore has no space to train its armed forces and, therefore, uses Taiwanese territory. However, Singapore has made it clear that it does not follow two China policies. In November 2016, China seized nine armoured vehicles that Singapore had shipped through Hong Kong on their return after training in Taiwan. The Chinese government launched a vituperative attack over conducting military exchanges with Taiwan. Singapore spends nearly 20% of its budget on defence, which illustrates how vulnerable it is. It took many months for relations to become normal.

With Deng Xiaoping on the ascendant, Lee’s role increased manifold. To quote Lee: “He was the most important leader I had met. He was a five-footer but a giant among men.” Both were Hakkas and this common linkage further cemented the friendship. Deng visited Singapore in 1978. He was very impressed with Singapore’s rapid economic growth and orderliness; he wanted to replicate the Singapore model in China. Lee, in turn, told him that China would benefit a lot if the capital and entrepreneurial skill of the Overseas Chinese was mobilised for economic betterment of China. To quote Lee: “I told Deng over dinner in 1978 that we, Singapore Chinese, were the descendants of illiterate, landless peasants from Guangdong and Fujian in South China, whereas the scholars, Mandarins, and literati had stayed and left their progeny in China. There was nothing that Singapore had done which China could not do and do better”. Lee visited China 33 times. Dr Goh Keng Swee, the man behind the Singapore miracle, went to China and advised it on the development of export promotion zones. It is estimated that the Overseas Chinese had contributed nearly 70% of the foreign direct investment in China.

Lee held the view that competition between China and the US is inevitable, but conflict is not. But with growing strains between China and the US, how will Singapore adjust to new realities? Unlike Deng, who subordinated foreign policy for the sake of economic development, Xi Jinping is more assertive and decisive. Washington and Beijing have started pressurising Singapore to change its foreign policy in their favour. And with China determined to solve the “Malacca Straits dilemma” by exploring alternative trade routes, Singapore’s locational advantage is bound to decrease. Equally relevant, the “Make in China 2025” policy might adversely affect the island republic. Over 16% of Singapore’s exports to China are manufactured goods and if China becomes self-reliant, Singapore’s exports are expected to decline.

It is very difficult to hazard how the winds of change would affect Singapore in the coming years. But if the past holds any lessons, one should not underestimate the resilience of Singapore’s leadership to face new challenges.

V Suryanarayan, Founding Director and Senior Professor (Retd), Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Madras (suryageeth@gmail.com)