India has had an impressive and evolving tradition of metal works dating back to the fourth millenium BCE. The beginnings can be traced to the Indus valley civilisation, and the tradition continues to this day. The Harappan metal smiths undoubtedly knew the art of using copper, bronze, lead, silver, gold and electrum, an alloy of gold and silver. The copper technology is the earliest. Harappans must have discovered early that adding tin to copper produced bronze, an alloy harder than copper but easier to cast. Also, it is more resistant to corrosion. Adding nickel, arsenic or lead enabled the Harappans to harden bronze further. The copper-bronze implements unearthed at Mohenjo-daro include axes, daggers, knives, spears, arrow heads, short swords, chisels, drills, fish-hooks, metal mirrors and so on. A remarkable tool of the Harappan civilisation was the true saw, a blade with teeth, able to cut through wood instead of merely gashing the surface. It appears that this was unknown elsewhere at that time.

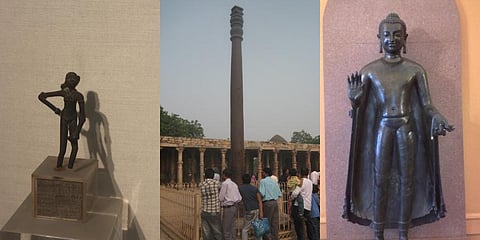

Besides the implements, very many bronze figurines of humans and animals have been unearthed from the Indus valley sites. The bronze figurines of a dancing girl, foot and anklet, bull, and so on at Mohenjo-daro and other sites are now well known and widely admired. These figurines were cast by the lost-wax process; the initial model was made of wax, which was then thickly coated with clay. When this was fired, the wax melted away, or was ‘lost’ and the clay hardened into a mould, into which molten bronze was later poured.

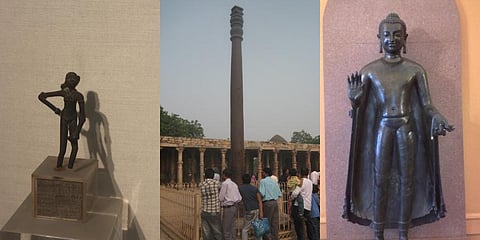

The Delhi iron pillar, which is more than 1,500 years old, is a metallurgical marvel. With a height of more than 7.2 metres, and a diameter of 40.6 cm, it is estimated to weigh over 6,000 kg. According to the Sanskrit inscription on its surface, it was ‘erected by Chandra as standard of Vishnu at Vishnupaada-giri’. Scholars have identified ‘Vishnupaadagiri’ with modern Udayagiri near Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh, and ‘Chandra’ with the Gupta emperor, Chandragupta-I Vikramaaditya (375-414 CE). It was brought to its present location in New Delhi’s Qutub complex around 1233 CE. Thousands of tourists visit this iron pillar, which is a ‘rustless wonder’, every day. Numerous experts, both Indian and Western, have tried to understand the secret of the pillar’s manufacture, and its rust-resistant nature. Recently, this property has been shown to be due to phosphorus together with iron; oxygen from the air contributes to the formation of a thin protective coating on the surface.

There is an iron pillar whose height is around 8.7 meters and which weighs 500 kg located at the Adi Mookambika temple in the Kodachadri hill area in Karnataka. It is the dhwajastambha (flag staff) of the temple. It is considered one of the oldest examples of ancient Indian metallurgy, and probably dates to before 600 CE.

The ‘iron pillar’ now located in Dhar town of Madhya Pradesh is actually fragmented into three parts. There was probably a fourth part, which is missing. According to local tradition, it was a victory column erected by the 11th century Paramara king Bhoja. The total length of the three fragments is 13.21 metres (43 ft 4 in) and the combined weight is estimated to be 7,300 kg, which is nearly 1,000 kg more than the weight of the Delhi pillar. At the time of its erection, it was probably the largest forge-welded iron pillar in the world.

With a height of 2.3 metres, width of 1 metre and a weight of over 500 kg, the huge bronze statue of Buddha, made between 500 and 700 CE in Sultanganj in Bihar, is very impressive. It is presently in the Birmingham museum, and is one of the important exhibits there. It was made by the same ‘lost wax’ technique that the Harappans used 3,000 years earlier. The technology used to produce the marvellous bronze statues in South India in the Chola period and later times too would not have been very different. Remember the magnificent Shiva Nataraja at Chidambaram and innumerable other divinities adorning temples, and now in museums and private collections too.

The tradition continues to this day. We have the artisan classes producing metal works using essentially traditional techniques throughout India, be it Swamimalai in Tamil Nadu, Bidar in Karnataka, Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh or many other centres in India. There is a considerable evolution of the technique. Consider the ‘Bidriware’ produced in Bidar, for instance. This technology originated in the 14th century CE. The Bidriware products are made of a blackened alloy of zinc and copper inlaid with thin sheets of pure silver. With each passing year, the products have undergone several changes at all levels.

M S Sriram

Theoretical Physicist & President, Prof. K.V. Sarma Research Foundation

(sriram.physics@gmail.com)