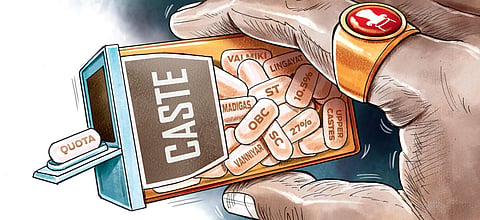

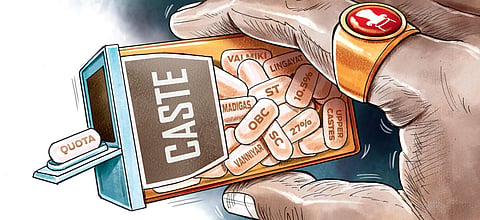

It suddenly appears that there is a lot of activity quietly happening around caste, more so in the southern states. This statement may be contested by the discerning, who may quite rightly ask, as to when had activity around caste in any part of India ever ceased or abated? True, but let’s look at the activity, gauge the rush and then conjecture what provokes the movement.

In Karnataka, B S Yediyurappa has been put to test by the largest sub-caste among his own Lingayat community. The Panchamasalis held a huge demonstration before the close of February and demanded that they be put under the 2A category of reservation in the Other Backward Classes (OBC) list. A couple of weeks before them, one of the largest OBC communities in the state, the Kurubas, decided that they should intensify their demand to put the community under the Scheduled Tribe (ST) list. Opposition leader Siddaramaiah comes from this community, but he has been wary of this demand. However, the mobilisation worked out by his rivals in the community has left him somewhat isolated, as much as Yediyurappa feels cornered within his own community. The fundamental asset of these two leaders has been their caste identity politics.

Also in Karnataka, the Valmiki community has demanded internal reservation within the ST quota. They want their share enhanced to 7.5% of the total ST pie. The similar demand of the Madigas among the Scheduled Caste (SC) for internal reservation has been a few years old. They continue to press for the implementation of the Justice Sadashiva Commission report, which recommends this. Amidst these demands from the subalterns, the BJP government in July 2020 created the Karnataka Brahmin Development Board, and its new schemes made news in February. As if on cue, a couple of days ago, it was reported that a serving IPS officer in Bihar had demanded a separate ministry for the socially and economically backward upper castes.

If one looks at Tamil Nadu, the bill to group seven SC communities as Devendrakula Velalars was tabled in the Lok Sabha, in mid-February. Internal reservation of 10.5% within the Most Backward Classes and Denotified Communities for the Vanniyar community was also cleared by the Tamil Nadu governor days before the Assembly election schedule was announced. All these demands may have been brewing over time, but the timing of their culmination is to be understood, and elections are only a limited excuse. There is a larger and long-term concern, or game, depending on how one views it.

In early March, Odisha said that it would start its survey of the OBCs in May. Karnataka had done a survey of the castes when Siddaramaiah was chief minister, but he had dithered over releasing it. Meanwhile, the Justice G Rohini Commission set up by the Modi government has been examining OBC categories to reorganise its 27% quota in Central government jobs and educational institutions. It apparently plans to have four sub-categories. A former judge of the Andhra Pradesh High Court and former chairman of the National Commission for Backward Classes, Justice Eshwaraiah, said a week ago that the methodology being used by the Justice Rohini Commission is “unscientific, atrocious and illegal.” Meanwhile, the Andhra Pradesh government in October 2020 had set up 56 corporations for the welfare of 56 separate castes. This was in the place of one single corporation earlier.

In the middle of all this turmoil is one of the final judgments of Justice Arun Mishra of the Supreme Court that advocated internal reservations. Mishra is the same judge who had praised prime minister Modi as a ‘visionary’ and a ‘versatile genius’. The judgment had said: “When reservation creates inequalities within the reserved castes itself, it is required to be taken care of by the State making sub-classification and adopting a distributive justice method so that State largesse does not concentrate in few hands and equal justice to all is provided.”

What are we to make of the scenario painted above? Is there anything specific to glean from the plan to redistribute quota? There could be two large reasons besides electoral politics, which is of limited utilitarian value. The first reason could be rather lazy and benign: The socio-economic backwardness is still so worrisome that governments in power, pressured to offer results and quick transformation, may be constantly tempted to tinker with quotas to ensure that the scaffolding built around hope remains intact. It is a kind of excuse, a fig leaf, for non-development and absence of progress. People are cleverly made to assume that since the quota formula is being rejigged, if not theirs, at least lives of their next generation would look up. It becomes an alibi for the perpetual postponement of work.

The second reason could be ideological. If there is clamour for internal reservation, and if the quota pie is too narrowly sliced and redistributed, the advantage would be so minimal and competition still intense that people may see little hope in reservations. It may put a powerful group among subalterns, who had till now cornered the largesse, in conflict with numerically larger sub-groups. Internal reservations may lead to internal dissension. This will alter the dynamics of electoral politics.

The expectation from this experiment is that people will get disenchanted with their caste identities and may prefer to gradually regroup under a larger identity, perhaps a religious one. This is an experiment that creates a mirage of a flatter landscape. Although seemingly naive in its assumption, this entails calculations deeper than what is apparent. The idea of one nation-one language-one religion-one emotion and eventually, the sway of a single party on a polity and society may work quietly for an older status quo and stratification among castes.

Sugata Srinivasaraju , Senior journalist and author

(sugataraju@gmail.com)