On 4 March 2021, NASA achieved a remarkable landmark in planetary exploration by soft-landing its rover named Perseverance on the Martian surface, marking the beginning of a new era of understanding the planet that had a lot of similarity with Earth billions of years ago. Mars was closest to Earth in March 2021. Such an opportunity comes once in two years. Making use of this, not only the US but also UAE and China had embarked on their Mars missions The UAE launched a spacecraft named HOPE intended for making remote observation of the Martian atmosphere and weather patterns. China’s Tianwen 1 mission is a combined orbiter, lander and rover for Mars exploration.

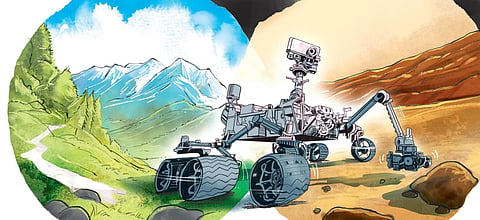

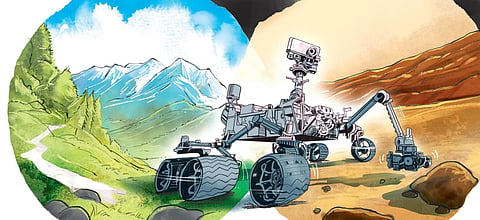

Out of these three missions, Perseverance is the most advanced. The fairly large rover will look for fossilised microscopic life. The landing site, namely Jezero crater, was a lake 3.5 billion years ago with its own river delta. It is hypothesised that water may have spread over 45 km wide with 600 m depth here. There could have been living organisms; one hopes to find biosignatures in this dry land. A unique feature of this mission is a small helicopter carrying a set of instruments for atmospheric studies.

Sending a spacecraft to Mars is hard and landing on the planet is even harder. The thin Martian atmosphere makes descent tricky and more than 60% of landing attempts in the past have failed. This time, NASA used all its past experience to arrive at the landing sequence using sophisticated sensors and rocket systems.

The orbiter is equipped to make remote observations using a set of cameras and radars, and will also act as a data relay centre. These sets of instruments will not only provide stereoscopic images but also assess the atmospheric constituents. The lander with the robotic arm will enable close observation and multispectral imaging of nearby regions. The main objective of the lander is to assess the surface conditions, analyse various samples of soil and rocks, and make observations of the climate. The aim is to determine whether Mars was inhabited once and whether it can provide opportunity for supporting life in the future.

Mars has always attracted the attention of humans due to its reddish hue that is different from other planets and stars. Its unique trajectory has been computed in India and Mesopotamia thousands of years ago. Later, towards the end of the 18th century, the invention of the telescope has enabled humans to have a closer look at this red planet. Science fiction has tried to imagine the existence of a Martian civilisation and speculated about the presence of extraterrestrial intelligent creatures. Though there is no physical evidence of any living objects on Mars as of now, there is a hypothesis that about two to three billion years ago, there could have been life there as on Earth.

Quite often questions are raised as to why we should explore Mars. Today, the existence of humans is solely dependent on Earth, which alone provides the right prerequisites for life support such as water, oxygen, carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen, and the right temperature among the planets of the solar system. There is always the fear of extinction of the human species either due to natural calamities or man-made disasters on Earth.

Prof Stephen Hawking, the famous theoretical physicist and cosmologist, once declared that mankind faces two options: Either we colonise space within the next 200 years and build residential units on other planets or we will face the prospect of long-term extinction. Almost all space-faring nations have long-term ambitions to make the space colonies a reality.

The nearest is the Moon, about 400,000 km away. But there is no atmosphere around it—no oxygen, hydrogen or carbon, essential to support life. The recent discovery by our Chandrayaan mission, confirming the presence of water in the polar regions, gives some hope. But the temperatures are extreme, ranging from −160°C in the permanently shadowed region to 200°C in the equatorial regions. Gravity is about one-sixth of Earth’s surface. Establishing a human habitat in these extreme conditions is a Herculean task but it may still be possible by establishing huge tents with artificial atmosphere and appropriate temperature. Almost everything has to be carried from Earth except power, which could be derived from the Sun. Such tents can accommodate people for short periods to conduct experiments or excavate some exotic material like Helium-3 that is not available on Earth. Beyond that, such a base can also act as a platform for launching spaceships to other planets or to interstellar space.

Right from the beginning of the space era, nearly 60 attempts have been made to explore Mars at close quarters. So far, four space agencies—NASA, Russia’s Roscosmos, the European Space Agency (ESA), and our ISRO—have put spacecraft in Martian orbit. With eight successful landings, the US is the only country that has operated a craft on the planet’s surface. Several spacecraft such as NASA’s MAVEN orbiter, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Odyssey; ESA’s Mars Express and Trace Gas Orbiter; and India’s Mars Orbiter Mission are transmitting data now from Mars.

These exploration missions have confirmed the presence of water on the surface and ice sheets beneath. The images show there would have been flowing liquids—maybe water or methane—river valleys, basins and lakes. This indicates there may have been large oceans in the early days. All these explorations have given rise to the hope that there could have been a thick atmosphere in Mars, which could have contained water vapour and supported life sometime back in history. But what brought the catastrophic phenomena that resulted in a hostile dry and dusty planet of today is intriguing and worth studying. It may throw some light on the large-scale destruction caused by climate change.

Often people ask this question: ‘When is India going to the Moon or Mars?’. We are in the process of developing Gaganyaan, which can carry three crew members to orbit around Earth and return. Taking off from that, planning a Moon mission may be feasible whereas going to Mars involves nearly eight months’ travel time one way, staying there for a few months and returning. It poses several technical and logistical problems. It may need nearly a hundred tonnes of material and supplies to be taken to an orbit around the Earth, assembled and sent to Mars, and brought back safely. Even with the largest rocket system in the world today, it may require nearly 10 launches for one trip to Mars.

In this context, Elon Musk the SpaceX founder, has come up with the unique solution of developing a huge rocket system that can take a nearly 100 ton recoverable and reusable module, which can not only survive the launch and reentry into Earth but also carry nearly 10 passengers to Mars and back. This a fantastic concept and development of the various systems are halfway through. Maybe in five years, a cargo mission to Mars may be feasible and in about 10 years, human flight to Mars and back. Musk has predicted that by 2100 about 100,000 people may travel to work or pleasure to Mars and return. This is fantastic foresight and a dream that is not impossible to realise.

For the moment, India has to be satisfied with robotic exploration of this nearest neighbour of the Earth that could be adopted to support life. India had made a small beginning by sending its Mars orbiter mission in 2017. Though it was an abridged configuration, it demonstrated our capability to travel nearly 40 million km and reach Martian orbit. It has also taken some close pictures of the red planet and provided some data on trace gases. We demonstrated our capability to have an orbiter, lander and rover mission through our Chandrayaan-2 mission. Though there was a small slip between the cup and lip, we demonstrated most of the technologies required for exploration of Mars. What is needed is to conceive unique experimental objectives and plan a mission to Mars, an opportunity for which may come about two years from now.

MADHAVAN NAIR

Former ISRO chairman