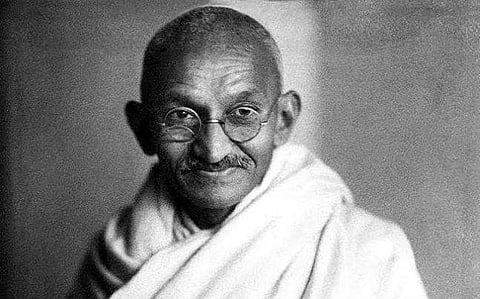

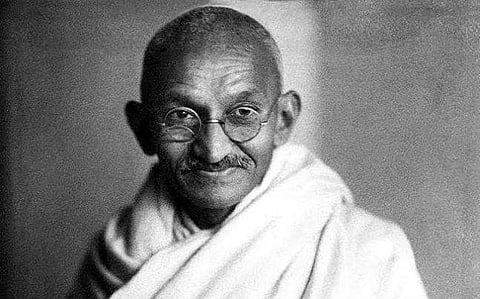

When we in India, more often than not, have resorted to violence and whipped up hatred, a few leaders in foreign lands were adhering to Gandhian principles of resistance to evil. Nelson Mandela, in many ways, was a practitioner of Gandhian values. Though they never met, they were linked by a passion to resist oppression through non-violence. So also Martin Luther King Jr. In an article on the 10th anniversary of Gandhiji’s passing away, King wrote that Bapu had done more than “any other person in history” to show that social problems could be solved without resorting to force. In that sense, he was more than a “saint of India, he belongs to the ages”. Vaclav Havel, playwright-turned-politician, who led the “Velvet Revolution” in Czechoslovakia and became the President of Czech Republic, expressed support and solidarity with the exploited and marginalised throughout the world. He was another great practitioner of the Gandhian form of struggle against tyranny and dictatorship.

In this essay, I want to highlight how the leaders of the Indian Tamil community in Sri Lanka followed the Gandhian form of struggle to end the stigma of statelessness. Gandhiji had a special attachment to the Indian Tamil workers, who were his trusted followers in South Africa. They were the epitome of simplicity, hard work and self-sacrifice. Referring to the untold sufferings and sacrifices of the Tamils—Narayanasamy, Nagappan, Valliamma, and others—Gandhiji said in a speech in London on 8 August 1914: “These men and women are the salt of India; on them will be built the Indian nation that is to be. We are poor mortals before these heroes and heroines.”

Gandhiji’s only visit to Sri Lanka took place in 1927. He went to Ceylon at the invitation of Handy Perinbanayagam, President of the Jaffna Youth Congress—which was based on Gandhian principles, was non-communal and demanded full independence. Unfortunately, it disintegrated in the 1930s, and politics on the island began to take communal overtones. Gandhiji’s objective was to popularise Khadi and prohibition. He visited all parts of the country. He was so touched by the similarity between South India and Ceylon that he referred to the latter as “India’s daughter state”. At the end of his visit, speaking in Colombo, Gandhiji advised the Indian community to identify itself completely with local aspirations just as “sugar in milk”. Gandhiji’s principled stance was in sharp contrast with that of China, which considered Chinese throughout the world to be citizens of China.

Nehru subscribed to the view that once India became independent, it would be able to support the demands of the Overseas Indians. But the newly independent governments, especially Ceylon and Burma, discriminated against the Indians on the issue of citizenship. Nehru advised the ruling elite that since most of the Indians were born there and contributed to the prosperity, they should be conferred local citizenship. In Ceylon, they were disenfranchised first and then rendered stateless. In 1964, Burma expelled thousands of Indians, the overwhelming majority of them Tamils.

Nehru’s principled stance on the question of citizenship went into flames in Shantivan on 28 May 1964. His successor, Lal Bahadur Shastri, on the advice given by C S Jha, Commonwealth Secretary, decided to solve the problem based on “give and take”. Without consulting the wishes of the concerned people, the countries entered into two agreements, in 1964 and 1974, as a result of which 6,00,000 stateless people, with their natural increase, were conferred Indian citizenship, whereas Ceylon agreed to confer citizenship on 3,75,000 people with their natural increase based on 7:4. The agreements were a betrayal of the Gandhi-Nehru legacy. Thondaman told me that he was not even given a visa to come to India to make representations to the Central and state governments.

The major problem confronting the Indian Tamil community from 1948 to 2003 was the stigma of statelessness. A born fighter, Thondaman never gave up hope. With a judicious mix of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary struggles, he was able to compel the recalcitrant and intransigent Sinhala leadership to confer citizenship to his people in various stages. Finally, in 2003, the government enacted a law under which all those born in Sri Lanka after October 1964 and who wanted to be permanent residents were conferred Lankan citizenship, which included even those who had acquired Indian citizenship but were yet to be repatriated to India.

Among the struggles that Thondaman led, special mention should be made of the “prayer campaign”. Despite the assurances given by President Jayewardene and Prime Minister Premadasa that they would soon find an amicable solution to the problem, the government began to drag its feet. The government had banned strikes and, therefore, that course of action was ruled out. Subsequently, Thondaman came up with the idea of a prayer campaign, which was essentially based on Gandhian principles. The objective was to bring about a change of heart among the Sinhalese leadership. On 29 May 1985, the Ceylon Workers Congress announced that a prayer campaign would commence from Thai Pongal (January 14) to Tamil New Year Day (April 14). The workers would pray from 7 am to 12 noon and then resume work. Thondaman held out the assurance that tea production would not be affected by the prayer campaign. The workers would pray that God should give sufficient wisdom to Jayewardene and Premadasa so that the government would soon implement the solemn assurances it had given to the Indian community. Gamini Dissanayake, minister-in-charge of the plantation industry, retaliated that if the workers did not work for five hours, they would not be paid wages for five hours. Thondaman responded: “In that case, we would pray for the whole day.” The prayer campaign, conducted during the height of the plucking season, electrified the nation. It had its desired results.

I had the opportunity of discussing the pros and cons of the prayer campaign with Thondaman a few days later. He said that given the circumstances, he did not know what to do, did not get sleep, and was pacing up and down in his room. Early in the morning, the idea of a prayer campaign came to his mind. I told him that Gandhiji, on similar occasions, used to say that he heeded the call of the “inner voice”. Thondaman was deeply touched and, five seconds later, I could see a twinkle in his eyes.

V Suryanarayan

Senior Professor (Retd), Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Madras

(The author was the Founding Director of the Centre in the University of Madras)

(suryageeth@gmail.com)