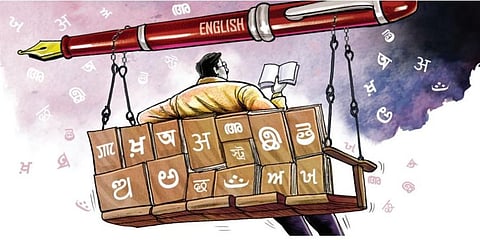

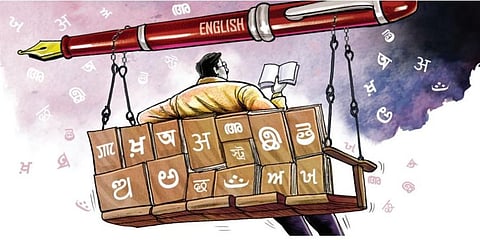

A private foundation funded by a tech billionaire in Bengaluru recently announced that it would offer sumptuous fellowships to translate non-fiction texts written (from 1850 onwards) in 10 Indian languages into English. The foundation’s intent is laudable and the possibilities are rich. The project will presumably ensure new facts, alternate world-views and uncommon thought processes available in regional tongues to illuminate the vibrant political and cultural discourses already taking place in English, the language of global influence and power.

Even as we compliment the translation project, we must recognise that it essentially enriches the English language. The regional languages, which would function like informants here, gain very little from this generous philanthropic investment. Some may dismiss this as needless quarrel and argue that the project offers a bigger stage for ideas tucked away in forgotten corners and neglected phonetic scripts. This may be true, but the point is that while the project helps widen the stream of knowledge in English, it does next to nothing to the cultures of the source languages. It does not help the primary users of these languages in their perceptions and engagements today.

There are other questions pertaining to the politics of translation but that is not the enquiry here. A purposeful speculation that one would like to indulge in is by asking the following: What if this translation project had been inverted? What if the foundation had funded non-fiction translations from 10 languages of the world into 10 Indian languages? What would have the impact been?

To ask this question is important because there is a divide in India between those who primarily access knowledge through English and those who operate basically in their regional languages. It is obvious that the former is in a minority while the latter is a diverse majority. There may be smaller subsets of those who may be bilingual or trilingual, but we are obviously looking at big categories. Here too, there is a qualitative difference as well as a class element between people who are bilinguals handling their regional tongue and English and those who happily glide between one regional tongue and another at various geographical intersections in India.

There is no definitive assessment available about the health of our regional languages in the last quarter century in terms of the nature of content offered to its speakers and readers via books, periodicals, newspapers, cinema, social media, television and OTT platforms. But we do know that the strides of globalisation and technology have provoked anxieties and insecurities in these linguistic cultures. It may not be inaccurate to say that this has resulted in their expressions becoming shriller, more chauvinistic and narrower than the grand liberal traditions imagined for them at the beginning of the 20th century, when their modern characters were being shaped. They had kept their windows wide open then; now they seem to have nearly shut them. A translation project that infused a fresh flow of diverse liberal content into these languages would have introduced readers into bigger and brighter ideas and naturally helped them recover their expanse and reconnect with the world. It would have helped partially stave off fundamentalist and exclusive ideologies that seem to have gripped everything local these days.

At the threshold of the 20th century, linguistic identities that eventually led to linguistic states were being crafted. Alongside imagining a new nation through the freedom movement, we were simultaneously fostering sub-nations and their nationalisms in our mind. People writing in the regional tongues at this historic juncture were furiously mixing the local with the universal to create a broad modern outlook. The influence of English and European languages was there, but as Kannada writer U R Ananthamurthy loved to put it, we were able to digest these influences to create something that was uniquely our own. The proportion and percentage of this influence was a constant source of debate but there was no question of shutting off the world.

The irony, however, is that as technology and commerce shrunk the world around the millennial bend, the regional tongues were attracted to regressive postures. There is yet another confusion that we have witnessed since, which is that the distinct agenda of the linguistic states have gradually allowed echoes of conservative nationalistic agenda. That is, the idea of a federation of independent states with a calculus of its own is slowly turning into one nation with assumed common cultural denominators. This has made diversity look like a curse and a sin and has severely jolted the rooted cosmopolitan traditions of regional languages.

In what may seem incredible today, one of the most popular prayers in Kannada (Karunalu Baa Belake) is a transcreation of an English hymn (Lead, Kindly Light) by John Henry Newman. The cultural markers in this poem are so original that generations of Kannada speakers have sung it without realising that it is a translation. This prayer was part of an anthology (published in 1926) called English Geetegalu (English Songs) by B M Srikantaiah, a revered figure of Kannada nationalism and modernity. Interestingly, the dedication in this anthology reads as follows: “To my students in the University of Mysore who believe in the blending of the souls of India and England these verses are affectionately inscribed.” The colonial context and its curriculum apart, the words ‘believe’ and ‘blending’ are so significantly placed that both need to be reassessed today. Later too in Kannada, modern sensibilities were shaped when thousands of pages of modern Bengali literature were translated from the original by people like Ahobala Shankara, who considered it not an act of literary authorship but as a service to the language and its new nation. The stories are similar in the other Indian languages.

In this backdrop and with the peculiar exigencies of our time, the private foundation’s translation project would have been visionary had it reversed its objective to help recover the liberal impulses of Indian languages.

Sugata Srinivasaraju

Senior journalist and author

(sugata@sugataraju.in)