In a significant judgement in the case, S Abirami v. Union of India and others, delivered on October 11, 2022, Justice G R Swaminathan of the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court declared that the principles of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019 “can apply to the Sri Lankan Hindu Tamil refugees”. Though Sri Lanka is excluded from the countries mentioned in the CAA, Justice Swaminathan maintained that the same principles apply to Sri Lanka and that the “Hindu Tamils were the primary victims of racial strife”.

Abirami was the petitioner; her parents were Sri Lankan citizens and had come to India as refugees due to ethnic fratricide back home, and they did not have valid travel documents. She was born in Trichy in 1993 and has been living in India since then. She is not a Sri Lankan citizen. She wants to make India her permanent home. She was issued an Aadhar card, but her efforts to obtain Indian citizenship have gone in vain.

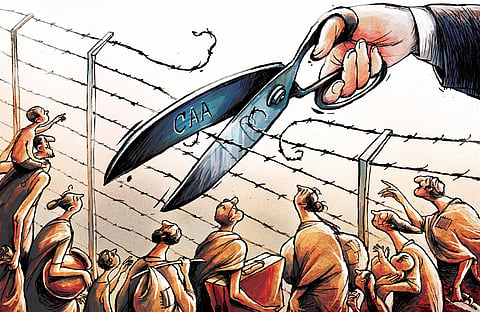

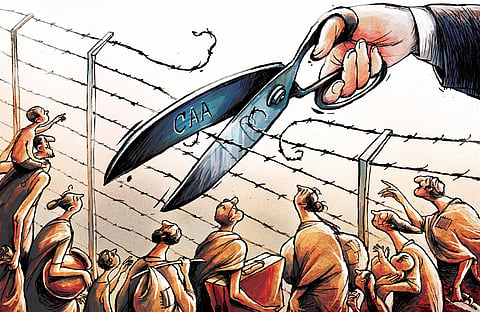

To quote from the judgement, the Sri Lankan refugees are “genealogically rooted to this soil and who speak our language and who belong to our culture”. To add, “Keeping them under surveillance and severely restricted conditions and in a state of statelessness for such a long period certainly offends their right under Article 21 of the Constitution of India.”The CAA marked a welcome change in India’s refugee policy. I was one of the first to welcome the Act, though I had opposed certain provisions. The exclusion of Sri Lanka from the list of countries was the main objection.

Secondly, I argued that the spelling out of non-Muslims in the three countries and subsequent criticism could have been avoided if the term “persecuted minorities” had been used. This would have shown India’s concern about the tragic plight of Muslim sub-sects like Shia and Ahmadiyya in Sunni-dominated countries. The Act also did not consider the Madhesis in Nepal, the Rohingyas in Myanmar, and the Hui and the Uyghurs in China, who have been persecuted.

New Delhi has not, for justifiable reasons, ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention nor the 1967 Protocol. These two instruments are based on the experience of the Western world and do not reflect the problems and prospects of refugees in the developing world. Moreover, according to UNHCR, the determination of the refugee status has to be made on an individual basis. Our experience had been a mass exodus from Tibet in 1959, from East Pakistan in the late 1960s, and from Sri Lanka since 1983. What is more, despite the presence of diverse groups of refugees, New Delhi has not enacted a national refugee law. Decisions are, therefore, taken on an ad hoc basis.

For example, thanks to the forward-looking approach of former Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M G Ramachandran, Sri Lankan refugees were permitted to work to supplement the doles given by the state government. On the other hand, the Chakmas, who came from Bangladesh, were not given that right.

In the absence of a national refugee law, judicial decisions have become extremely important. Certain judgements need to be highlighted.

In the famous case, NHRC v. State of Arunachal Pradesh, the Supreme Court held, “The State is bound to protect the life and liberty of every human being, he be a citizen or otherwise.” The National Human Rights Commission also acts as a watchdog as far as refugee rights are concerned. In the famous case, P Nedumaran v. Union of India, delivered by Justice Srinivasan of the Madras High Court, an “interim injunction” was granted, restraining the Government of India from repatriating the refugees.

It may be recalled that following Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, then Chief Minister Jayalalithaa wanted to repatriate Sri Lankan refugees, and the government officials used “strong-arm tactics” to get their consent in forms that were printed in the English language. To save embarrassment, then Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao, on the advice of then Foreign Secretary Muchkund Dubey, allowed the UNHCR to open an office in Chennai to certify the “voluntariness” of repatriation.

Thus, in a crucial moment, the Government of India upheld non-refoulement, the basic principle of International Humanitarian and Refugee Law. Article 33 (D) of the UN Convention states: “No contracting State shall expel or return (refouler) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his (or her) life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

Two other judgements delivered by Justice Swaminathan deserve mention. In the first judgement delivered on June 17, 2019, Justice Swaminathan instructed the Government of India to consider applications for citizenship submitted by the Tamil refugees of Indian origin. The Government of India maintained the legal status of these people was that of illegal immigrants.

In the second judgement in another case, Justice Swaminathan pointed out that under the Citizenship Act, 1955, Section (3) (1) (a), “a person born in India on or after the 26th day of January 1950, but before the 1st day of July 1987 shall be a citizen of India”.

The petitioner was born in India after January 26, 1950, and, therefore, is an Indian citizen. The petitioner produced his birth certificate, and his genuineness is not in doubt. The learned judge referred to a similar case in the Delhi High Court where the petitioner was conferred Indian citizenship.

The petitioners should take up one task immediately. Many refugees follow the Christian faith and are also subjected to discrimination and persecution in predominantly Buddhist Sri Lanka. Justice Swaminathan should be requested to also include Christians as a persecuted group who deserve Indian citizenship.

V Suryanarayan

Founding Director, Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Madras

(suryageeth@gmail.com)