When there is a rise in communal incidents, like in Karnataka for the past few months, three conjectures are often made: one, an election is round the corner; two, there is ideological intransigence that keeps ploughing on no matter what; or three, there is too much economic pressure with vanishing jobs, soaring prices and crumbling infrastructure, and the government wishes to desperately divert attention. In the case of Karnataka, all three may be true at this juncture.

There is no less dangerous option among these three conjectures because all of them have the exact same impact on our society. A relatively less evil reasoning does not make the poison more palatable, because poison has only one effect on whom it is served. However, when people react to communalism, they do so from their own particular and peculiar perch in society. For instance, those in business react when communal incidents threaten their investments and profits. If a low-intensity communal explosion is happening, and if it does not immediately threaten to down their shutters, they are happy to look the other away. They are structurally designed not to think long-term because brooding over uncertainties can cloud their entrepreneurial wisdom and risk-taking. They do look for long-term stability but do not mind if that stability comes in the form of a compromised democratic avatar.

Last week, Kiran Mazumdar Shaw, a celebrity businesswoman, intervened when bigotry in Karnataka was not leaving the headlines alone. She addressed the chief minister through a tweet and said communalism had the potential to destroy Karnataka’s “global leadership” in information technology (IT) and biotechnology (BT). She urged him to “resolve this growing religious divide”. What she said deserves unreserved appreciation. She has always been outspoken, but this time she had spoken with a greater ounce of conviction.

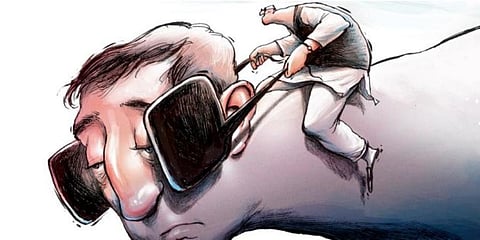

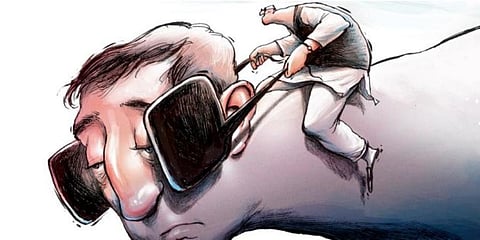

But why Ms Shaw’s reasoning is somewhat limited to the future of business leadership and not the well-being of society in general is a question that does not resolve itself. If business prospects are not harmed but a certain authoritarian and communal agenda is cleverly pushed, then does that become acceptable? Karnataka’s communal frenzy did not take shape the week she commented. It has had a pernicious trajectory for over two decades. To just research what the IT and BT leaders in Bengaluru have argued for over the last two decades, what they have spoken or not spoken about, who they have overtly and covertly supported in self-interest will make for fine dissertations at their favourite ivy league institutions. It will expose their trapeze act.

Anyway, within two hours of having tweeted her mind, Ms Shaw called the Karnataka chief minister a “progressive leader” when he had not put on display any progressive trait. Within 24 hours, she again praised the chief minister because he had called for “restraint before going public on social issues.” That was hardly a condemnation of anything that was happening in Karnataka by him, but it appears she had to balance, and balance quickly. The same day she retweeted another Bengaluru Member of Parliament speaking about upgrading industry skills and internships, when he was demonstrating ideological aggression in front of the Delhi chief minister’s residence. There were different voices on her timeline from the same camp. Was it pressure or was it about thinking in silos? Ever since, Ms Shaw’s Twitter timeline has made for an interesting study in the balance of opinions. Many in power at the Centre and in Karnataka, who have never expressed even minimum anxiety over growing communal tensions, are variously accommodated.

Administrative collapse in Karnataka has been apparent and communalism, it is argued, is an effective diversionary tactic. The fact that the next Assembly elections is fast approaching and could even be advanced makes it even more attractive and compelling. The stories of Covid corruption have been tumbling out ceaselessly. Many of them were discussed in the state Assembly. The state government claims to have spent over `15,000 crores to counter the pandemic but still could not stop deaths of 24 people due to oxygen shortage in Chamarajanagar. Covid job losses have been huge. The small-scale industries minister reported in the Assembly recently that in the last two years, 754 factories were shut down and nearly 46,585 people lost their jobs. Since this is government statistics, one must assume that the number is far greater. Besides, this is one small statistic from one sector, a compilation of many such areas, formal and informal, would put the loss numbers at a staggering level.

According to government statistics again, nearly 20,000 crores of grants remained unspent in various departments and those included funds meant as scholarships for SC and ST students. It is also public knowledge that nearly 15 of the around 30-odd government departments have underperformed. Amidst this, public work contractors have written letters of complaint to no less than the prime minister that those in the government are demanding 40% commission. One should realise here that they are complaining because corruption is way above ‘normal’ levels. A contractor is not expecting a zero-corruption corridor but is unable to deal with unchecked greed. The money-making impulse also gets highlighted when one notices that salaries of drivers and conductors are delayed but the desire to buy new buses is intact.

As collapse and contradictions pile up, there is perhaps an escape that has been scripted: The anti-cow slaughter and the anti-conversion bills are piloted with fervour; there are riots in remote areas and questionable disbursement of compensation; there is a debate on the saffron flag hosted by a senior minister; there is of course the hijab and halal controversies; there is the exclusion of Muslim traders; Tipu Sultan is made a hate figure for a zillionth time; and it suddenly comes to light that 330 cases against bigots have been withdrawn. The Constitution is obviously subverted, and of course the word ‘unconscionable’ has been rendered anachronistic.

Sugata Srinivasaraju

Senior journalist and author

(sugata@sugataraju.in)