The United Nations recently announced that the world population has crossed the 8 billion mark and that next year, India will overtake China and become the most populous nation in the world. Further, India’s population will continue to rise until 2064.

The UN identified India as the biggest contributor to the world’s population growth in the last 12 years, and the increase was highest in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. This trend may continue over the next decade as well.

This has major implications for India, not only because the nation will have more mouths to feed, but because of the social and political implications of uneven population growth among religious communities.

Some weeks before the UN announcement, the general secretary of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Dattatreya Hosabale, had lent his voice to an issue that has been agitating the Hindu mind for a long time—the distinct change in religious demography in India and the dwindling Hindu population over the last few decades. He felt that there was a need for a population policy and “population control”. In his view, the government must evolve a uniform population policy which is applied evenly across religious communities and geographies, and strictly enforce anti-conversion laws.

An analysis of the census data over the last 50 years establishes that demographic change has gone against the Hindus. For example, the percentage of Hindus in India in 1961 was 83.4%. It dropped to 79.8% in 2011 and is certain to drop further when the religion census data of 2021 is available. On the other hand, the percentage of Muslims was 10.7% in 1961. It increased to 14.2% in 2011. The changes in these communities’ populations in the last 50 years can be attributed to the huge variance in their decadal growth. While the national average for decadal growth was 17.7% in the last census, and the Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains grew at a rate lesser than that average, the Muslims multiplied by 24.6%. For example, while the Hindus multiplied by 16.8% between 2001–11, other religious communities grew at the following rates—Christians (15.5%), Sikhs (8.4%), Buddhists (6.1%) and Jains (5.4%).

Equally significant is the fact that the Muslim population grew in 27 states in the country between 2001–11. It rose in percentage terms from 30.9 to 34.2 in Assam, 24.7 to 26.6 in Kerala, 11.9 to 13.9 in Uttarakhand, and 25.2 to 27 in West Bengal.

Addressing the Working Committee of the RSS, Hosabale said that apart from conversions, the human traffic across the border was altering the demographics in several districts of North Bihar, apart from other states.

Hosabale reminded the Sangh’s Working Committee that past experience showed that population imbalance had grave repercussions on a nation’s geography as well. His reference to conversions finds resonance in the dramatic increase in the Christian population of Arunachal Pradesh (18.7 to 30.3), Manipur (34 to 41.3) and Meghalaya (70.3 to 74.6). The RSS believes that religious conversions in several of these states have brought about unprecedented demographic changes. For example, Christians constituted 52.98% of the population in Nagaland in 1951. But in just 60 years, their population jumped to over 90%. Meanwhile, the Hindu population in the state crashed from 14.36% to 7.7% between 1981 and 2001.

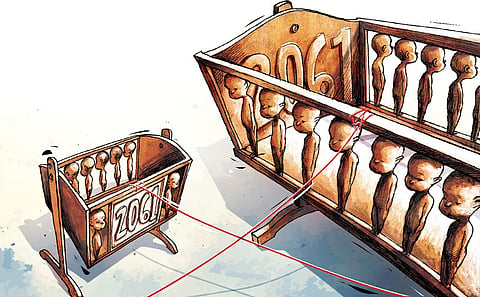

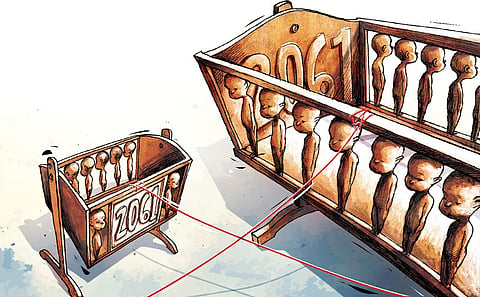

The anxiety expressed by leaders of the RSS stems from the detailed demographic research done by A P Joshi, M D Srinivas and Jitendra Bajaj, authors of Religious Demography of India and scholars in the Centre for Policy Studies in Chennai. After assessing the 2001 census data, they came up with a rather gloomy prediction that the adherents of the Indic religions would become a minority in India in 2061.

This study has indeed come as a wake-up call for Hindu groups in the country and has been the reason for the demand for a uniform population policy. Needless to say, major demographic changes have significant political, geographic and social consequences.

And this is the central worry of the RSS, which Hosabale has articulated. Further, the concerns of the RSS flow from the fact that the Hindus have become a minority in eight states and union territories. They are Mizoram, Nagaland, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Punjab, Jammu & Kashmir and Lakshadweep. In other words, the Hindus are in the minority in a quarter of the states in the country. What are its political and social implications, and what impact will this have on national and internal security and social harmony? These questions appear to be uppermost in RSS’ thinking and are worthy of some introspection and debate.

The Modi government will have to take cognisance of these demographic changes and evolve a population control policy that has universal application but is non-coercive. In fact, the family planning programme initiated by the Congress Party between 1975–77 turned out to be so intimidating and unpopular that future governments refused to even talk about it lest they lose public support.

In order to ruthlessly pursue its objective, the Indira Gandhi government set sterilisation targets for government servants, including policemen and school teachers. Those who failed to meet the targets were denied salaries or arrested under the draconian national security laws in vogue then. The worst example of that government’s coercion was the police action in Meo Muslim-dominated Uttawar village in Haryana, where all males aged 8 to 80 were bundled into police vans, taken to a primary health centre and forcibly vasectomised. This resulted in such revulsion towards the programme that it wrecked the small family campaign and contributed in no small measure to India’s population growth.

The Modi government will therefore need to steer clear of these pitfalls and evolve a policy which will be more persuasive and less menacing in order to bring the numbers down and, at the same time, ensure that it applies to all religious denominations. How will the Union government respond to these demographic realities and the concerns of the RSS? Will the Modi government pick up the gauntlet?

A Surya Prakash

Former Chairman of Prasar Bharati and scholar of democracy studies