Citizenship in India is not a Constitutional right. It is a statutory right emanating from the Citizenship Act. Yet, citizenship is a condition precedent for invoking many fundamental and Constitutional rights. It is a right to have other rights.

No wonder the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019, which fundamentally altered the criteria for grant of citizenship for those fleeing from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, led to protests across the board. Many, on the other hand, supported it. At least a few felt that there is no big deal about it, as the law only protects certain religious minorities from a few neighbouring countries. The Amendment seeks to exempt illegal migrants from these countries if they are Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis or Christians. They can also obtain Indian citizenship with relaxed conditions if they have been in India before December 31, 2014. Such preferred categories will no longer be treated as “illegal migrants.”

The political agitation against the CAA, which subsided with the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, gave way to a legal challenge, which though belatedly, the Supreme Court has decided to take up for consideration. The Court has already asked the lawyers to place their written submissions. The impact of the CAA, together with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), is thus going to be juridically deliberated.

There are pertinent questions: Does the classification based purely on religious grounds tally with the basic features of the Constitution, especially secularism? Is the classification sensible or reasonable? Is the purpose of the enactment in tune with international treaties that bind us? What will be the plight of the prominent minority in India who have been here for decades when asked to prove citizenship for NRC, which is stated to be a necessary extension of the present move?

Part II of the Constitution is on citizenship. It contains Articles 8 to 11 dealing with this topic. At the time of the commencement of the Constitution, every person having domicile in the country was given automatic citizenship by way of Article 5. Other categories entitled to citizenship also were mentioned.

Article 6 deals with the citizenship of persons who migrated to India from Pakistan. According to this provision, religion is not a barrier, though there are other conditions. Article 7 is about the rights to citizenship of certain migrants to Pakistan, and Article 8 is about the citizenship of certain persons of Indian origin residing outside India. More significantly, Article 11 empowered Parliament “to regulate the right of citizenship by law”.

Parliament made the law in 1955, and the Citizenship Act came into being. It talked about citizenship by birth, descent, registration, naturalisation, incorporation of territory, etc. The Act was amended several times.

Citizenship in India was never conceived as a religious idea anywhere in the Constitution or the Citizenship Act as it originally stood. During the Constituent Assembly Debates, Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar said that we, as a nation, cannot oppose apartheid in South Africa and plead for a racial or sectarian concept of citizenship in India. Sardar Patel, on April 29, 1947, advocated for “broad-based nationality.”

But there were opposing ideas also in the Assembly. “If the Muslims want an exclusive place for themselves called Pakistan, why should not Hindus and Sikhs have India as their home?” argued P S Deshmukh on August 11, 1949.

In the tragic episode of Partition, religion mattered. Pakistan, as a nation, was born essentially on religious grounds. It chose to become what it is today. It negated secular democracy.

We, on the other hand, opted for a different path. We created a democracy envied by many across the world, despite its inherent deficits. The ghosts of Partition did not haunt us. We chose to be a liberal, inclusive, and secular republic. Romila Thapar has put it correctly: “We cannot relate our political evolution only to the politics of religion associated with Partition, since the mutation to a secular democracy was far more significant.” (On Citizenship, Aleph, 2021).

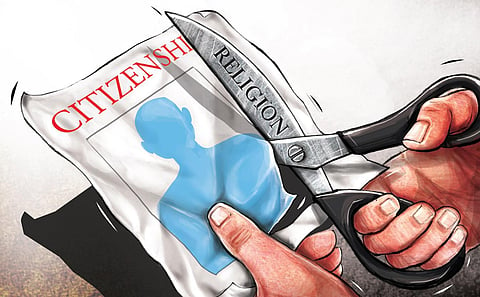

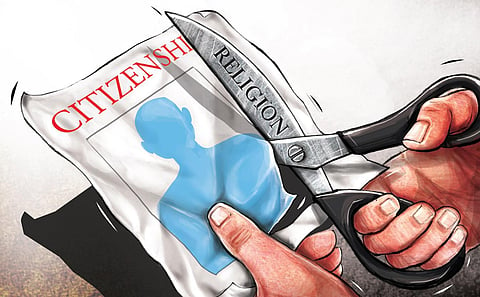

The 2019 amendment to the Citizenship Act, however, radically altered the very idea of citizenship. For the first time, religion became an explicit parameter for citizenship.

There are two ways of examining the issue. One is legal and Constitutional, and the other is social and political. Legally, one can question the rationality of the preference. Why are only the victims of religious persecution and not other victims given sympathetic consideration? Why are the persecuted persons from Sri Lanka not considered? Why are the Ahmadis from Pakistan, Christians from Bhutan, or Tamilians from Sri Lanka fenced out? What is the big difference between the illegal migrants who came here before and after December 31, 2014? What exactly is the purpose of the Amendment?

The ultimate problem is not merely logical or technical. Starting with the CAA, something more fundamental is at stake in the present process. The Constitutional lens of common brotherhood gets replaced by a religious lens coloured by divisiveness. Yes, we are towards an ethnic democracy, as Christophe Jaffrelot put it.

In S R Bommai (1994), the Supreme Court said that secularism is a basic feature of the Constitution. Our election laws bar the use of religion or religious symbols during campaigning. There were instances where the courts set the electoral results aside when events demonstrated a breach of such provisions.

Of late, like socialism, secularism in India, as a value, got damaged. The electoral laws on misuse of religion are more honoured in their breach than in compliance. Majoritarianism showcases a kind of primitive democracy rather than a Constitutional democracy. The philosophy behind the divisive provisions in the CAA nullified the Constitutional ethos and placed sectarianism above pluralism. In the process, we negated the humanitarian content of international law also. The doctrine of non-refoulement is a globally accepted moral code.

It is not the CAA on its own that is potentially divisive and dangerous. When the State asks the people to stand up and prove their citizenship by way of NRC, lakhs of people belonging to the targeted religion might suffer due to the heavy and unbearable burden of formally proving their citizenship with ancestral documents. This is, sadly, a device that can threaten the nation, which means its people. The new legislation has the flavour of religious revivalism. This is in tune with what Deshmukh visualised in the Constituent Assembly.

The point, however, is whether it passes Constitutional muster.

Kaleeswaram Raj

Lawyer, Supreme Court of India

kaleeswaramraj@gmail.com

Tweets @KaleeswaramR