As this column goes to press, I am looking forward to participating in the ThinkEdu Conclave, March 8–9, organised by The New Indian Express. In this column, I want to highlight two issues flagged in my new book, JNU: Nationalism and India’s Uncivil War before the decision makers of the land, the distinguished audience and the general public when it comes to the crisis in higher education in India.

The first issue concerns India’s narrative wars. In ongoing discussions, friends often ask me why the dominant, Left-Liberal, Congress-sponsored narrative about India is so durable. They wonder how it continues to rule not only mainstream media, but also academics, diplomacy, culture, arts, literature and other domains of soft power, even when the UPA is out of power at the Centre and the Congress routed in most states in India.

But to understand the persistence of residual Left-Liberal soft power, the explanation that the Congress ruled nearly 60 of the 75 years of post-Independence India is not entirely adequate. Actually, even after the manifest failures of Congress-style socialism and secularism, their idea of India is prevalent not only in our country, but in many parts of the world.

The reason for its depth and tenacity is that it is more insidious than historical. The fact that this idea of India, as a continuation of the older colonial narrative, is easily supported by current Anglophone and Anglocentric, neo-colonial stereotypes is not understood by many. In this narrative, much of the glory of ancient India is a myth, propped up by the Right-wing, Hindu nationalist fantasies of a lost golden age, which in itself is an orientalist invention.

The neo-Ambedkarite debunking of ancient India as caste-ridden, oppressive and thus fit for rejection is, therefore, one vital plank. This unyielding opposition to any positive reconsideration of classical India is crucial to the modernist-Marxist-secularist agenda. It helps perpetually to divide Hindus between the guilty savarnas and the outraged avarnas, the latter constantly in need of reverse discrimination, if not appeasement.

Then there is the minority constituency to cater to. Here, the argument advanced is that the Hindu majority is unfit to assume and wield power. That’s why Hindu deities, festivals, practices and texts are ridiculed or undermined at every opportunity. Numerically significant Muslims and the theologically well-equipped Christians are discouraged from joining the majoritarian formation led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Instead, minorities are constantly provoked and bamboozled to criticise the ruling dispensation.

Minority resentment and insecurity is stoked by highlighting, even fabricating, atrocities against them, thus demonising the majority as perpetrators of violence and hatred against the weak and defenceless sections of society. Shaheen Bagh is only the latest example of this. The entire history of India must be seen, as per the LeLi strategic playbook, as one endless series of foreign conquests, with little native resistance or spine, let alone a coherent cultural, social, economic or political order.

India is thus projected as a weak state that should not aspire for greatness, either domestically or internationally. It should remain a second-rate power, part of some larger alliance led by one superpower or other. Any assertion or will to power is castigated as jingoistic sabre-rattling, dangerous to national security and threatening to peace in the neighbourhood.

India as a weak, divided country, with a fragmented society, internally contradicted polity, controversial history and confused self-identity would be easier to rule by people who claim to be its guardians by virtue of not belonging to any group, region, language or community. Essentially outsiders, they gather around them representatives of various interest groups and powerbrokers, distributing the largesse of office in proportion to their supporters’ efficacy or utility. This non-patriotic alliance of opportunists has only one binding glue: their own selfish interest to retain power at all costs.

When we feel badly about ourselves and our past, when we have little hope for the future, our Left-Liberal elites become happy. This is because they can tell us that only they can keep this ragtag, divided nation, with its unwashed, benighted masses, together. That is why I have been arguing that the battle that we face as a nation is not only between two political formations or ideologies, but between two ideas of India itself. One is informed by idealism, hope and the prospect of greatness. The other stokes our fears, resentments, doubts, confusions and insecurities.

The second issue has to do with brain drain. We all know how at the outbreak of the crisis in Ukraine, there were over 17,000 Indian students in that country, mostly studying medicine. Many of them are now back in India. The effort to airlift them home is heroic. But have we spent enough time finding out why they went to Ukraine to study medicine in the first place, without even knowing the language of the land?

We witness the phenomenal flight of young people out of India each year after failing to find a place in our reservation-locked system. The estimates are that there are over 10 lakh Indian students abroad, of which over 2 lakhs each are currently in the US and Canada alone. Only a small percentage of them are on scholarship. The remaining pay huge fees, often taking massive loans to cover costs.

We not only suffer from brain drain, but also from capital flight. Apart from the US and Canada, there are thousands of Indian students in the UK, Australia, Singapore and so on. Thus, we have created a system in India that encourages the export of both talent and money. We spend an estimated $15 billion or more on these students each year, enough to fund over 300 JNUs in India.

As somebody who has spent all his life studying or teaching, I am worried. As a country, we are not only falling behind in the field of education but will soon cease to be competitive if we continue like this. The only reason why we have survived is due to the tremendous creative energies of our people, who find informal and unorthodox solutions to extremely complex problems.

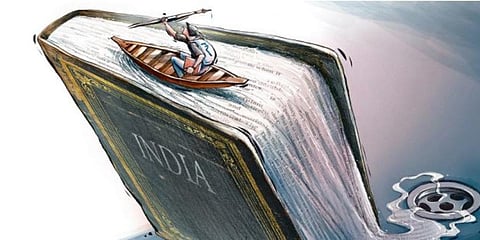

The entire future hangs in balance. If we lose what little we have now, it is difficult to imagine how we can remain at the forefront of the new economy, which is a knowledge economy. This neglect of our education system is especially lamentable if we remember that we have been a knowledge society for over 3,000 years. But today, we seem to have fallen into tremendous ignorance and apathy.

We can change all this. India can be a profitable hub of education not only in the Global South, but in the wider world. Brands such as the IITs and IIMs already have global recognition and bandwidth. I was told that the government has finally allowed the former to open campuses abroad, but nothing on the ground has happened as yet.

There are several other Indian universities and institutions that can also be competitive, attractive and affordable if they become true centres of learning and excellence, rather than just of politicking, picketing or picnicking. If we don’t react fast, foreign universities, where our best youth will prefer to study despite the hefty fees, will overrun our own country. That, unfortunately, will be the prelude to the recolonisation of India.

A lot needs to be done. The question is: Do we have the political will to do it?

Makarand R Paranjape

Professor of English at JNU

(Tweets @MakrandParanspe)