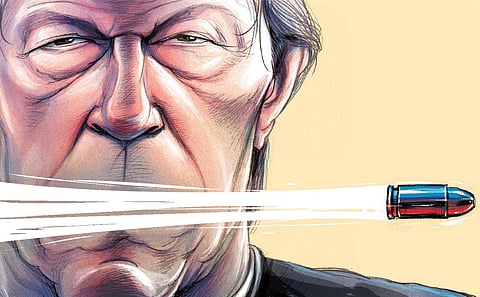

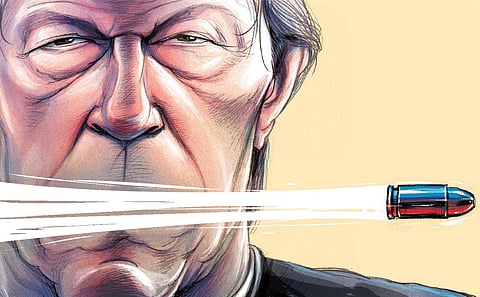

First, a barrage of fire from an AK-47 had everyone atop the container standing alongside Imran Khan, ducking for cover. And then, a shot from a pistol, a scuffle and a chase after the shooter who, within hours of being apprehended, admits in a confessional statement to police that he had acted alone even as reports swirled of a third shooter who had gotten away.

While questions remain on how bullets shot from street level could injure Imran and his cohorts perched on a container, Thursday night’s failed assassination attempt at the massive political rally in Wazirabad in the heart of Pakistan’s most populous state of Punjab, against the hugely popular cricketer-politician Imran Khan, was simply waiting to happen.

Was it a warning shot meant to wound but not kill the man who has refused to go quietly, unwilling to swallow his pride at the unceremonious ouster from the office of prime minister barely seven months ago?

And the people’s anger against the army? The attack by a mob on the Lahore Corps Commander’s home, hours after Khan was rushed to Shaukat Khanum hospital—founded in his mother’s name—with bullet wounds to his legs that will leave him unable to walk for weeks, is unprecedented in a country where the ubiquitous army-intelligence establishment has always played a behind-the-scenes role, pulling down governments at will. The people’s acquiescence to the army’s meddling in politics is almost a given. Until now.

Is the ordinary Pakistani’s patience at an end? Has Pakistan reached a pivotal moment in its history? The growing popular anger at the targeting of politicians who challenge the army’s writ, and the establishment’s open meddling, installing pliant leaders who do their bidding while jailing those who don’t, silencing critics such as popular journalist and Imran sympathiser Arshad Sharif who was gunned down in Kenya, cannot be tamped down. Has Pakistan reached a tipping point?

Khan’s move to position himself as an alternative to political heavyweights like the Bhuttos and Sharifs, whom he maligned with impunity while inveigling himself into the good books of the military establishment, was a bid to reinvent himself from the ‘Kaptaan’ of the world-beating cricket team to the ‘Kaptaan’ of Pakistan.

His Teflon-like ability to ward off damaging allegations that he is as corrupt as his political rivals has boosted his already soaring popularity among the young and the restless, who have refused to blame him for his inept governance that precipitated the country’s economic distress.

The establishment has struck back. Charges that his controversial wife, Bushra Bibi, was behind his illegal appropriation of expensive gifts from heads of state have led to a case for his disqualification from active politics. But Khan, in keeping up a tirade against the army, has remained stridently vocal about an American-led conspiracy to remove him from office, citing diplomatic messages from Pakistan’s envoy to Washington. His anti-American, anti-establishment stance, plus his espousal of Islamist groups like Daesh and the Taliban and the Tehreek-e-Taliban, which has a growing footprint in his home state of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, has, however, led to unease in Army GHQ, Rawalpindi, as much as Washington.

The establishment has attempted to counter him with leaks of his conversations with confidantes on how to use the ‘cypher’ from Washington to further the conspiracy narrative. Meetings with serving army chief Gen Qamar Jawed Bajwa and Inter-Services Intelligence chief Lt Gen Nadeem Ahmad Anjum where he is heard offering Gen Bajwa an extension as army chief as a quid pro quo for a return to political office saw the ISI chief air the story at a first of its kind press conference.

While the military-establishment using the media to air its unease publicly is certainly new, political parties’ using street power to pressure the army is not.

Then-President Gen Pervez Musharraf faced the wrath of lawyers when he tried to replace the then-chief justice in 2007. It was the street power of another long march by Imran Khan that brought the Nawaz Sharif government to its knees. And a united joint opposition, made up of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) as well as the powerful Maulana Fazlur Rehman faction, now calling itself the People’s Democratic Movement, that challenged the army-backed Imran Khan, even as the anti-army Nawaz and his daughter Maryam ceded space to the pro-army Shehbaz Sharif.

The fiery Benazir Bhutto, similarly, was prodded into talking to her bete noire Gen Musharraf at the behest of Washington, which wanted a return to civilian rule. That the establishment did not see her as a trustworthy partner was amply clear. The firing on Imran’s convoy was an eerie reprise of the failed attempt against Benazir in Karachi in October 2007 and her assassination two months later, as she was heading out of the very park where Pakistan’s first prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan was assassinated in 1951. Imran Khan’s uncharitable comments about Benazir then, saying she ‘only had herself to blame’, must come back to haunt him.

Either way, Khan’s on again-off again relationship with the establishment came to a head only after his famed falling out with the army chief over the appointment of a successor to ISI chief Lt Gen Faiz Hameed and a successor to the army chief himself. Neither Gen Bajwa nor the serving head of the Inter-Services Intelligence, Lt Gen Anjum, deeply upset at being dubbed ‘traitors’ by Khan, are willing to do a deal.

But with Gen Bajwa’s term coming to a close by November end, Khan will use street power and tap the sympathy wave that this assassination attempt has generated to call for fresh elections in the next few months rather than wait for 2023. Any election now will only work to his advantage, allowing him to call the shots and anoint the new army chief. While the army is said to be examining the efficacy of imposing martial law, detaining Khan could create more unrest, jeopardising key IMF loans needed to steady the economy.

In the weeks that followed Nawaz’s second coming in 1997, one remembers how the political parvenu Imran Khan was drawing diehard Nawaz supporters into his inner circle. Today, although former PPP stalwarts like Shah Mahmood Qureshi are standing by his side, sources say, Qureshi approached Bilawal Bhutto Zardari only days ago, asking for an honourable re-entry. Similarly, many former PML-N

top guns-turned Khan supporters have been knocking on the doors of Nawaz’s Avenfield home in London.

The bullets haven’t worked. Will splitting the PTI down the middle be the only option for the harried establishment?

Neena Gopal

Foreign policy analyst and author

(neenagopal@gmail.com)