Two important recent developments in the chequered history of reservations in India deserve our attention. On November 7, the Supreme Court, in a 3-2 verdict by a five-judge Constitutional bench, upheld the 10% reservation for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) in admissions and jobs within the unreserved category. It was in 2019 that this new category of reservation was introduced in the 103rd Amendment Act. U U Lalit, the former Chief Justice of India, and Justice S Ravindra Bhat, ruled that the amendment should be struck down, while the majority, justices Dinesh Maheshwari, Bela Trivedi, and J B Pardiwala, in three separate judgments, upheld the amendment.

While the major political parties applauded the decision, the usual “LeLi” intellectuals and crusaders opposed it. As senior advocate Mohan Gopal, who appeared against the EWS quota, put it, “The verdict can be seen as an assent towards normalising anti-representative and anti-democratic pursuits in the country. The objective of reservation was to give adequate representation. It is not a tool to alleviate poverty or financial backwardness.” He promised to file a new review petition to challenge the verdict.

Many are under the mistaken belief that the 10% EWS quota comes out of the total 100%, that is, it is a quota over and above the statutory 7.5% (ST), 15% (SC), 27% (OBC, to the exclusion of the “creamy layer”)—making a total of 49.5% under the Central government quota system. They think this is similar to how, in some states, reservation is more than the Constitutional limit of 50% and is as high as 100% (Lakshadweep), Sikkim (85%), Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland (80%), or, as with a major state such as Tamil Nadu (69%). No. The EWS 10% is part of the 50% of the so-called general quota. Therefore, it does not signify a special category like ST, SC, or OBC, but one that is within the so-called unreserved category. This is also the reason that the other categories—or their champions—who complain against the EWS quota, are mistaken. The EWS quota is not at their expense.

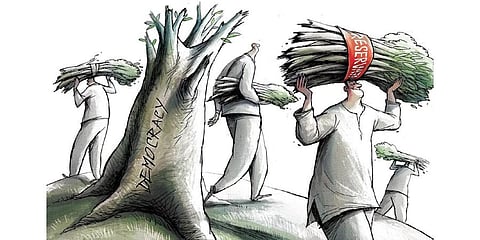

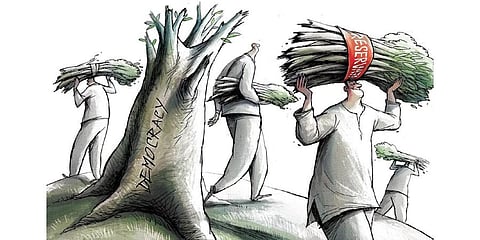

The problem is that reservation is justified as a means of social upliftment whereas it is primarily an economic measure. It is not that the social advancement needs of those who enjoy its benefits are not met, but that these latter are a subset of economic empowerment. Not the other way round. The arguments against perpetual reservations are many and, indeed, this may not be the best place or time to rehearse them. But the fact is that they are socially divisive rather than integrative and, ironically, inversely mirror the very system they wish to replace.

Being entitled by birth to never-ending privileges is the opposite of moving from a caste-based to a casteless society. It is, to invoke Dr B R Ambedkar, the very antithesis of “the annihilation of caste”. Instead, reservations set up a supposedly corrective social order, which ends up privileging disadvantage, historical injustice, and endless reparations—instead of merit or competence—as the basis of opportunities of advancement. It is my belief that the spirit of the Indian Constitution, where each citizen is guaranteed equal rights and opportunities regardless of religion, ethnicity, or caste, is contrary to reservations. The sooner this pernicious system ends, the better.

This is what brings us to what is perhaps an even more important development. The apex court, on August 31, had asked the Central government to clarify its stance on various PILs filed by the National Council of Dalit Christians and others to extend the benefits of the SC reservations to Hindus who converted to other religions. In its reply, the government stated that it was not in favour of extending the benefits of reservations to Hindu converts to Christianity and Islam because they “did not suffer the social stigma of untouchability”. More pertinently, the Centre referred to The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order of 1950, which had directed that reservations in education and jobs for those who belong to the SC community may be given only to Hindus, Sikhs or Buddhists.

In the present case, however, the danger is even more grave. If reservation is extended to SCs who have converted from Hinduism to Christianity or Islam, it would actually incentivise proselytisation and weaken Hindu society. In fact, there is a strong case to reverse the present entitlement of non-Hindu STs (Scheduled Tribes) to reap this harvest; only those STs who identify as Hindu should get the benefits of reservation, not those who do not or who have left the Hindu fold.

The Abrahamic faiths cannot have it both ways. They cannot claim their deprivations which supposedly originate in Sanatana Dharma while proclaiming the equality of all believers once the latter embrace Christianity or Islam. If the caste system persists after a convert has left their ancestral fold and joined the ranks of believers, then the professed “equality” of the latter is a chimera, if not a fraud.

Why should Hindu society have to bear the brunt of the failures of Abrahamic faiths? It is like saying all the ills come from Hinduism and all the paybacks from the latter. Let the state pay for the ills of Hinduism by guaranteeing reservation to converts while the faiths they converted into give them both respectability and social mobility in this world, and salvation in the next.

Such are the ruses of those who have, since before Independence, tried to denigrate and even destroy Hinduism, countermand its majority, and incentivise leaving the Hindu fold. A supposedly pro-Hindu dispensation, such as the present government led by Narendra Modi’s BJP, can scarcely afford to support such religious skulduggery and sleights of hand.

No wonder that last month the Centre appointed a commission under former Chief Justice of India, K G Balakrishnan, to examine the demand to grant Scheduled Caste status to those Hindus who converted to Christianity and Islam. In its affidavit, the government argued that there is no evidence or documented research to establish that the disabilities suffered by SCs persist after they opt to change their religion.

If all converts out of Hinduism are arbitrarily given the perks of reservation, wouldn’t that itself be tantamount to social injustice? While the Centre’s stance is right, we should go a step further. We must re-examine the toxic theology of reservations root and branch. The real question is who has the courage to bell the cat of reservations. The sad answer, at least at present, is no one. But the ruling BJP has made a beginning.

Makarand R Paranjape

Professor of English at JNU

(Views are personal)

(Tweets @MakrandParanspe)