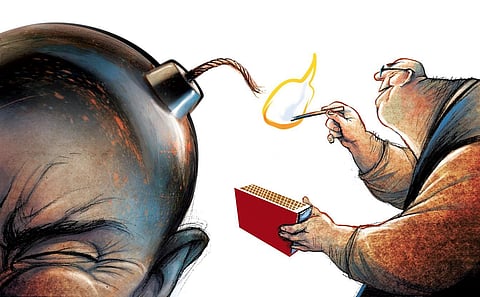

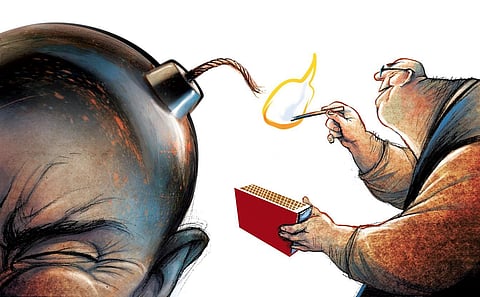

The rise of hate speech in the country in recent years has been alarming. Often, the leaders who make offensive remarks are either part of the power or proximate to it. As such, if at all, theoretically, they commit certain offences as defined in the Penal Code or other enactments, the law is often not set in motion. Selective use, non-use or misuse of the law is the country’s new abnormal. Sometimes, an appeal for genocide is ignored by the authorities, whereas a comedian’s show gets cancelled because of an artificially apprehended law and order issue.

The nation has changed for the worse, politically and culturally. Certain reports indicate that since May 2014, there has been a 490% increase in hate speeches by prominent personalities, the majority of whom are politicians. Around 124 reported instances involving 45 politicians have been noted during this period. Fanaticism has developed a new vocabulary shared by the majority and minorities. It has contaminated India’s public debates.

The public, especially influential persons, should be given a free hand in criticising the institutions and the individuals who run the institutions. Not only the government but the legislature or the judiciary also cannot claim immunity from people’s criticism. The free flow of opinions is a fundamental requirement for any working democracy. The Indian Supreme Court has warned against any move to curtail such freedom. In Sakal Papers(p) Ltd. v. The Union of India (1961), the court said that “the state cannot make a law which directly restricts one freedom even for scouring the better enjoyment of another freedom”.

The question, however, is, what is the remedy when ministers, members of the legislature, and the like openly make hateful and derogatory comments that either tend to split the society or substantially damage the dignity of the targeted group or individual? In such cases, the precious rights of the individuals are infringed not by the state as such but by those who are, in a way, part of the state and bound to speak and act constitutionally. It is a question as to whether such rights violations could be tackled only by the victims, adopting private laws. Dealing with this situation takes work. The courts cannot, normally, gag anyone and pre-empt a speech as it will amount to curtailment of freedom guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. A restriction should be reasonable and can be done by a law made by the state. Even such laws should satisfy the constitutional requirement indicated under Article 19.

In exceptional cases, gag orders would be justified. The top court has also said that when the speech creates hostility among the different groups, it could attract penal consequences. In State of Karnataka v. Praveen Bhai Thogadia (2004), the Supreme Court held that if the speeches “are likely to trigger communal antagonism and hatred”, the concerned authorities should issue prohibitory orders. In recent times, the Supreme Court has issued repeated directives regarding hate speeches and hate crimes. The judgments in Tehseen Poonawalla (2018), Kodungallur Film Society (2018), and Amish Devgan (2020) illustrate this point. In Kodungallur Film Society, the Supreme Court said: “Hate crimes as a product of intolerance, ideological dominance and prejudice ought not to be tolerated; lest it results in a reign of terror. Extrajudicial elements and non-State actors cannot be allowed to take the place of law or the law enforcing agency.” Thus, the jurisprudence on the subject is almost well-settled. But the menace continues. The law laid down by the court is not translated into action on the ground due to a variety of reasons related to power and politics. A free and fair police system that can set the law in motion in the event of hate crimes, irrespective of the political colour of the accused, is imperative for maintaining the Rule of Law. The Supreme Court, in Prakash Singh Case (2006), made a judicial initiative for independent police, which again was sabotaged by the executive.

Some speeches may not fall within the ambit of crimes as defined in the statutes. They, too, might impact the dignity of individuals who may be otherwise helpless. In nations like the UK and Australia, the governments were concerned with the Code of Conduct prescribing certain ethical boundaries on the speech and activities of the public functionaries. These are instances of self-regulation by the persons at the helm of affairs. Such an initiation has not happened in India. We need to consider it.

When political leaders try to reap electoral benefits through divisive agendas, there is little possibility of such leadership acting against hate speeches and other disparaging utterances by public functionaries. Even elections are fought on religious labels, clearly violating the prohibitory and penalising clauses in the Representation of People Act (1951).

In the case of aggressive speeches other than those amounting to offences, we need to evolve an institutional mechanism. An Ombudsman for this purpose might be a good idea. Currently, the existing system, like the Human Rights Commission, both at the national and the state level, should be able to take cognisance of hate speeches and fix liability on the concerned even when no crime as such is made out in the speech. After all, every divisive or disparaging speech could lead to a massive human rights violation. The definition of human rights occurring under Section 2(d) of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 would endorse this aspect.

Here again, there is a need to ensure functional autonomy for the human rights panels. The political appointment process immensely damages many of our institutions, and the Human Rights Commissions are no exception. The constitutional courts have jurisdiction to examine the commissions and omissions of the human rights panels. This judicial vigilance must be ignited if the rights panels refuse to act during aggravated hate speech having massive impacts. Responsible citizens and organisations must take a proactive role to set the law and the court in motion. They should resort to the device of Social Action Litigation (SAL).

We find even the ministers shouting about shooting ‘the other’ during communal riots. This is shocking. There is a growing concern among the public on the silence of leaders who are regarded as more mature and experienced than the hatemongers of their own folk. This is a silence amounting to guilt. Ultimately, more than any device or institutional mechanism, including the courts, it needs a vigilant public to guard against divisive politics. As said by Judge Learned Hand, “…A society so riven that the spirit of moderation is gone, no court can save;…a society where that spirit flourishes, no court need save…”

Kaleeswaram Raj

Lawyer, Supreme Court of India

(Tweets @KaleeswaramR)