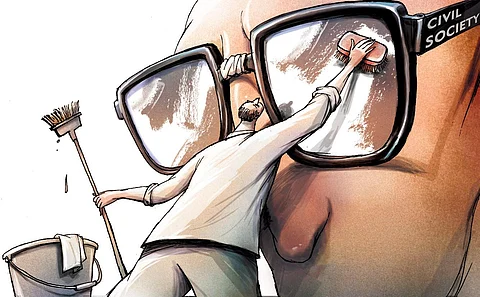

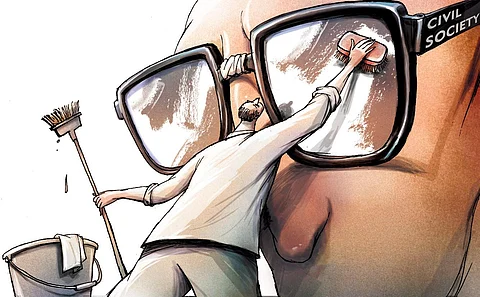

The reinvention of democracy has to go beyond electoral systems, current models of governance, and the conventional question of civil rights. One needs a theory of civil society because civil society is the humus for reworking the democratic imagination. After the authoritarianism of the Emergency, it was civil society that recharged the batteries of the somnolent democracy with institutions like the People’s Union for Civil Liberties and journals like the Seminar. Today when the idea of the Opposition has become passive and inert, the role of parties is predictable. One needs civil societies to revitalise a passive sense of democracy.

Mere dissent or a simple protest will not do. One needs new imaginaries to reinvent democracy. Imaginaries, as the Greek philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis explained, add a new sense of possibility and a new frame of alternatives to society. They catalyse dreams into feasible institutions. Civil society has to combine the idea of the local and the cosmopolitan, or what Gandhi dubbed as Swadeshi and Swaraj, to create a new vision of alternatives.

This column will focus on three kinds of social movements necessary for renewed democratic imagination. Firstly, civil society has to go beyond the nation-state to renew the idea of the Earth as an imagination. The ideas of the Earth, ethics and the Anthropocene have to be woven together. Secondly, India needs a new rethink around peace. It has to go beyond the official text of security and borders. Thirdly, civil society has to rework the idea of knowledge to challenge the hegemony of expertise. The citizen has to be seen as a repository of original knowledge, not merely a passive consumer of it.

The idea of the Anthropocene is an attempt to focus on the damage man has done to the Earth. The period after the Holocene has been dubbed the Anthropocene by Dutch chemist Paul Crutzen to mark the rise of man-made damage on Earth. But the Anthropocene as a discourse and as a genealogy of imagination date back to the ideas of Russian biologist Vernadsky and French Jesuit scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin—both pondered about the role of man on Earth. There is considerable controversy about the dates. Some mark the beginning of the Anthropocene with the advent of the industrial imagination, and some to the atomic age. Many anthropologists attribute it to the invention of America and the genocide of the tribes. Around five to six million Indians disappeared during the so-called conquest of the West.

The second debate centres around the nature of responsibility. Many scholars blame capitalism and the West, claiming that the Anthropocene was a result of western consumption and industrialism. But today we have to go beyond the immediacy and parochialism of such a radicalism and think of nature as unity. We have to rework nature as a cosmology to rescue the Earth. Imagine if every school or college begins by saving a dying plant species or a dying language. Civil society becomes a trusteeship of memory and diversity around the tribal, the teacher and the housewife. Nature has to be seen as more than a resource. We need new sacred groves of imagination to sustain the diversity of nature. In fact, the Directive Principles of the Constitution must list out measures to protect ecological sites, including rivers, and provide a new notion of rights for nature. Indian civilisation and spirituality have to rework themselves into a new idea of responsibility and a more vigorous celebration of nature.

In protecting nature, we inaugurate our moment to peace. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa was a great Gandhian invention. Created by Mandela and Desmond Tutu to restore sanity and peace to post-Apartheid South Africa, it needs to be extended. The violence in Kashmir and the northeast needs a healing touch, the ethical repair of the Reconciliation Commission. Healing needs truth and a realisation that truth can create more peace than security. When a nation-state is caught in debates on security, it is civil society that must rescue it. Civil groups like the university activists fighting everything from Narmada to genetic monoculture, and the housewives as envisioned by Ela Bhatt, and other feminists, must demand an end to the brutality of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA). The Truth Commission in India would expand the Gandhian imagination and create a new effervescence around the idea of the Satyagrahi. India would begin a new set of experiments regarding the truth about itself. India must exorcise the silence around state violence, and only civil society can perform this role with its ethical acuteness.

The vision of the Anthropocene and the idea of peace must extend to new ways of reading knowledge. This knowledge should create new ways of confronting genocide and the erasure of people labelled as "outdated." One needs a vision beyond technocracies. Craft acquires a centrality along with a concern for livelihood. A way of life and a way of living are built around life, giving alternatives of knowledge. Such knowledge is based on diversity and plurality.

One is reminded of biologist Hans Jenny. He walked into class at Berkeley and showed a set of slides. He then asked his class to identify the pictures. The smarter ones claimed they were impressionist paintings or the work of the French artist Monet. Jenny smiled and said they were slides of soil. The soil under the microscope looks beautiful. He advocated the rights of different soils to exist. Similarly, we have to look at the rights of the ecosystems and marginal species and create a new knowledge democracy for nature.

All this requires that the school and the university reinvent the idea of knowledge. Civil society must not only rescue the university from its current despondency but create a new knowledge system. Interdisciplinarity must become a new form of trusteeship and in the future a new kind of guardianship for the university. The idea of life transcends reductionism to become more life-giving. We need a new kind of Pugwash movement to expand the dream of new cosmologies and new methodologies of knowledge, where knowledge is playful rather than industrial.

With these three moves towards ecology, peace and knowledge, democracy gets redefined beyond a rudimentary idea of citizenship and rights. The marginals must find a new voice, and our country a new way of reinventing civilisation. By reinventing civilisation, India achieves a sense of life and life-giving activities. That is the dream we have to look for—a civil society that thinks and acts towards a different future and different ethics.

Shiv Visvanathan

Social scientist associated with THE COMPOST HEAP, a group researching alternative imaginations