The idiot relief that the Karnataka election provided has barely lasted a week, as the Congress engages its greatest enemy—itself. Amid continued infighting, the celebrations vis-à-vis opposition unity disappear into thin air over Mumbai, Kolkata, and Bengaluru. A friend, who is more a classic grammarian rather than a political scientist, warned me, “Do not confuse opponents with the opposition. Opponents are single, discreet, atomistic, and antagonistic. An opposition is a collective with a vitality and mindset of its own. The Modi regime has random opponents but faces no real opposition.” I realised my friend was both grammatically and politically correct.

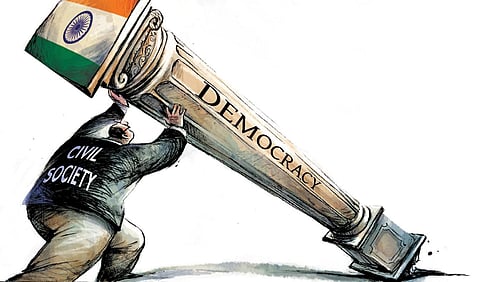

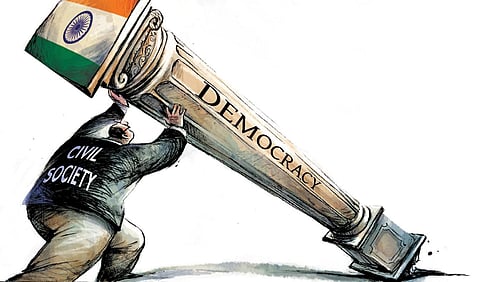

Reflecting on it, I realised that the tragedy is deeper. The cause lies not just in the mediocrity of the opposition but in the failure of civil society initiatives. India celebrated the vitality of civil society after the Emergency. The Emergency triggered the creativity of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) and People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) and gave the charisma of dissent to the university. The Emergency gave dissent respectability. Today’s civil society seems to be dead. It is so impoverished that one has to re-emphasise the crucial, critical and life-giving nature of civil society. It is civil society that makes India pluralistic, providing for alternatives beyond the ritualistic game of electoralism. It provides a compost heap of ideas that makes democracy a continuous drama of experiments.

The silence of civil society is the greatest victory of the majoritarian regime. The disintegration of civil society was achieved systematically. The BJP merged the nation state and democracy, making patriotism the greatest virtue, and dissent the dominant political vice. Secondly, it turned minoritarian politics into a mechanical affair. Political violence against minorities was now a standardised prelude to all elections. What was once an electoral reassurance of agency and a statement of political concern now appears starkly distant and indifferent. At a recent conference, a Jesuit scholar put it pointedly. He said, “I’m tired of being a minority, I want to be an Indian and a citizen in a civil society. The idea of the minority in India becomes a perpetual loyalty test for marginals and ethnic groups. It smells of threat rather than an evocation of rights.”

The regime’s destruction of dissent is a macabre ritual. It first transforms the language of development into a sacred complex and then arrests environmentalists as non-believers and anti-nationals. It batters the university to an intellectual pulp, destroying any possibility of criticism or alternatives. It then creates a huge net by labelling all activists as urban naxals. It demands an officially correct citizenship. As a result, the silence of civil society is deafening.

However, one must also admit it is a self-inflicted injury. The Left, today, is almost moronic in its passivity. It has no sense of creativity, either regarding work and labour or in a more general parliamentary sense.

The civilian Left has withered as an imagination, leaving space for a frivolous and pompous liberalism. In fact, mediocrity as totalitarianism dominates the public space as civil society withers in silence. We have to look for unexpected domains to ambush the BJP with the playfulness of dissent.

One needs the Anthropocene as a new imagination, where the human recognises that he or she is damaging Earth. The idea of humanity as an ecological hazard is something our regime does not understand but civil society as a repository of civilisation can. By using religion and reworking spirituality, civil society can create new institutions as footprints for itself.

Civil society has to create a new sense of the commons, rework the rights of nature and create a new mode of constitutional thinking that can challenge the regime and its Adanis. Civilisation in its plurality and sacredness has to challenge the arid secularism of the nation state. The emphasis should now be on diversity, and civil society needs to rewrite the Constitution beyond the Enlightenment era imagination. Civil society in a Gandhian sense has to absorb both Swadeshi and Swaraj, creating a new perspective to challenge the parochialism of the majoritarian State.

Civil society has to think more internationally to function more creatively in local terms. Peace now becomes the new portfolio of civil society as it attempts to redeem the national security state and its obsession with surveillance. Civil society has to provide a pedagogy, re-teaching the state the language of pluralism. One brilliant example of this is the late Ela Bhatt’s work on the grahani of peace. She showed that housewives should not be restricted by current definitions of home or patriarchy. The housewife becomes the new inventor of peace, rethinking war beyond security and sustainability. She has to create a new sense of care built around an understanding of the way women suffer during war and violence. The housewife uses the imagination of the household to think pluralistically. Visualising multiple layers of possibilities that go beyond the frozen nation state, peace has to invent new forms of hospitality, memory and caring.

Religion has to be reworked and the theological wisdom of philosopher-activists like Raimondo Panikkar, Desmond Tutu and Thomas Merton has to spread a new creativity of peace. Local gurus should also rethink the religion of peace rather than build ashrams to cater to the egoism of corporates. Our religions should use their cornucopia of metaphors to create new scenarios of peace with China and Pakistan. Democracy must become the new pretext for hope and experiments. The Jesuit journal Pax Lumina captures such a vision of peace built around a South Asian imagination.

Most of all, civil society should offer new possibilities of childhood which go beyond the industrialised and clericalised tutorial college model touted daily in our newspapers. We have to remember that children are dreamers who are playful, imaginative and quirky—precisely the characteristics civil society needs today.

Let me explain through a little anecdote. A child was running around his neighbourhood observing all the gossip surrounding King Charles’ coronation and the accompanying demand for the return of the Kohinoor. A bit later, I heard a familiar recitation with an unexpected twist:

“Pussycat pussycat where have you been,

I’ve been to London to look at the queen.

Pussycat, pussycat what did you do there?

I frightened the Kohinoor under the chair.”

One needs to imitate the happy impudence of children for civil society to stand up to the authoritarianism of the majoritarian State.

Shiv Visvanathan

Social scientist associated with THE COMPOST HEAP, a group researching alternative imaginations