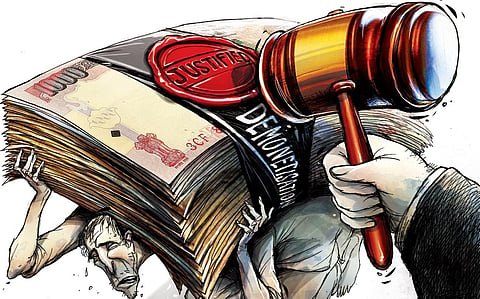

Demonetisation verdict: Rhetoric and reality

The judgment of the Supreme Court in the demonetisation case has evoked a political debate. The ruling party hailed the verdict, while the opposition tried to find solace in what Justice Nagarathna said in the dissent. How do we read the judgment? Does the judgment politically or morally endorse the Centre’s policy? Is the majority judgment legally convincing? What are the ultimate lessons that we should learn from the whole episode?

Demonetisation was a policy decision. Even if a policy is unwise or detrimental to many or even a majority, unless it reflects a patent illegality or clear breach of fundamental rights, the court will not interfere. This legal position is almost well settled. In a relatively recent judgment in Small Scale Industrial Manufacturers Association (2021), the SC reiterated this principle. Demonetisation was, however, not an ordinary policy. It came out abruptly. It was dramatic. It altered the country’s economy drastically. Secrecy was the hallmark of the ‘consultation’ which led to it, as otherwise, it was bound to defeat its intended objective. But as an economic measure, it was a big flop. It resulted in the death of many. It deprived a large number of people of their employment, trade, and livelihood. It resulted in immense human suffering, yielding no benefit. Nearly 99.3% of the banned currency notes came back to the banks.

A basic legal issue involved in the case was with respect to the interpretation of Section 26(2) of the Reserve Bank of India Act. This provision speaks about the power of the Central government to demonetise “any series of bank notes of any denomination”. The majority said that the provision could be invoked by the Centre by demonetising the whole series since ‘any’ means ‘all’. On the other hand, Justice Nagarathna dissented and held that Section 26(2) does not authorise the Centre to demonetise the whole series of ₹500 and ₹1,000 currency notes. There is enough space for academic discourse on this issue.

In the absence of any judicial interdiction, the process of demonetisation went on and ended with disastrous consequences. The government’s intention is now endorsed by the court. Yet, it was a foolish step, which again, unfortunately, was not a lookout for the court. The majority on the Bench said that the decision-making process was not vitiated. The Central Board of the Reserve Bank recommended it. The Centre acted on it. The court has no expertise to assess the success of the process, said the majority. Strikingly, the majority also said that the process satisfied the test of proportionality. That is to say, the measure taken was proper, proportionate, and justifiable in the light of the stated intention. It also said the 52 days period for the exchange of notes was quite reasonable.

The majority judgment calls for criticism on several counts. Demonetisation occurred more than six years ago. Its consequences are now evident and judicially assessable to an extent. While doing this assessment, the court must apply the proportionality test correctly. Also, the court must see the extent of the violation of the rights that was brought in by the decision. The majority judgment, though cryptically says that the Centre’s action has satisfied the proportionality test, lacks any analysis of this aspect. The majority should have explained how and why the policy decision is judicially justifiable.

A policy decision that adversely affects fundamental rights cannot escape constitutional scrutiny. The judgments in Premium Granites (1994) and Kalpana Mehta (2018) show this aspect. In Kalpana Mehta, the Supreme Court said that “The Constitutional Courts cannot sit in oblivion when fundamental rights of individuals are at stake.”

The Supreme Court has demonstrated this principle recently in the case of the Covid-19 vaccine policy. The court effectively interfered with the government’s decision, though it was a matter of economic policy on the face of it. The proposition in the suo moto case titled In Re: Distribution of Essential Supplies and Services During Pandemic (2021) illustrates this point. The court said that it could “conduct deliberations with the executive” to see whether “justifications for existing policies” can “survive constitutional scrutiny”. Thus, the government was forced to restructure its policy for ensuring access to vaccines for the masses, either free of cost or at a reduced price.

Demonetisation was a tragedy that required an examination in the context of a large-scale violation of fundamental rights. The way in which it impacted the people’s right to trade, to work and to live was the central issue that the majority on the Bench was bound to address. Let it be now stated clearly: This aspect was totally ignored by the majority on the Bench. A comparison of paragraphs 3 and 95 of the majority judgment will show that even the questions on fundamental rights which were vaguely framed earlier, i.e., questions (iii), (iv) and (v), were subsequently dropped by the court. Thus, the most significant part of demonetisation escaped judicial scrutiny. This makes the majority view inadequate and incomplete. The judgment is, therefore, quite unrealistic.

By turning a blind eye to human suffering because of the process, the majority verdict also happens to be one without a sense of constitutional compassion. The majority said that the court could not replace the wisdom of the executive with its wisdom. This conventional reasoning could not have been made in a project that was implemented and failed, resulting in a massive rights violation. There is no question of the court supplanting its wisdom when the lack of ‘wisdom’ of the government had its impact already. But the majority said that the court is not concerned with the consequences of the action. If so, there was nothing left for a substantial adjudication.

In the end, the Centre had a technical win in the litigation. The Supreme Court did not doubt its intentions. Nor did it criticise the Centre for the drastic consequences of the measure. The court limited its decision to “pure legal issues”. But the country’s experience because of demonetisation is bitter. Its memories are horrifying. It was a calamity that should not, and hopefully, will not occur in future. One cannot hush up the agonies faced by a nation using a judgment of the Supreme Court. After all, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr said: “The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience.”

Kaleeswaram Raj

Lawyer, Supreme Court of India

(Tweets @KaleeswaramR)