On July 17, a young engineering student tragically took his life by jumping from a university building in Bengaluru. He had allegedly resorted to copying during an exam using his mobile phone. University officials claimed that when confronted for this act, the first-year student was overwhelmed by the fear of severe consequences, resulting in him taking the extreme step. The question that lingers is, what could be more ‘severe’ than losing one’s life?

The distressing phenomenon of student suicides has been on the rise not only in Bengaluru but throughout the country. According to data from the National Crime Records Bureau, in 1997, there were nearly 5,000 reported cases of student suicides. Fast forward to 2020, and we had to face some tragic data which revealed that a young life was lost every 42 minutes. A rough calculation reveals that 34 lives were lost in a single day, and the total number of student suicides in that year alone totalled a staggering 13,000. These figures are undeniably alarming.

Despite the alarming frequency of these tragic incidents, neither the seriousness of the problem nor the gravity of the issue at hand seems to have been adequately recognised or addressed. In India, we have often tended to view suicide as an isolated and individualised event. The failure to hold institutions and systems accountable and to acknowledge their shortcomings has only exacerbated the problem. Our inability to recognise that suicides represent a complex intersection of public and mental health issues has prevented us from implementing effective solutions. Our refusal to analyse the situation comprehensively has further complicated the issue, impeding the development of lasting solutions.

Addressing this grave issue requires the collective effort of various sectors of society, including families, educational institutions and government bodies. Parents play a pivotal role in educating children about the value of life and fostering awareness about mental health. The family unit is the primary social structure that helps shape children’s dreams and aspirations. In urban settings, where both parents often work, quality time with children is a rarity, leading to limited communication and strained relationships. Nevertheless, the parental expectation that children must excel in all areas, particularly academics, remains unaltered. The proliferation of offline and online coaching centres despite requiring substantial financial commitments is indicative of this pressure. Unfortunately, the understanding that not all children can excel in everything is often overlooked.

Students are not machines; their unique talents and dreams are sometimes overshadowed by parents imposing their own aspirations and disguising their selfishness with the promise of a secure future. When these high expectations go unmet, tension, stress, anxiety and depression take hold of children, ultimately contributing to them having suicidal tendencies.

Mental health issues among students have become widespread especially after the Covid pandemic. Parents often assume that their children are doing fine and that schools and colleges will address any issues that arise.

While many educational institutions do have counsellors to help with personal problems, relying solely on them is unfair. Educational institutions often have limited resources to tackle mental health issues. Therefore, it is crucial for parents to actively engage with their children, maintaining open communication and attentive listening to identify behavioural problems early on.

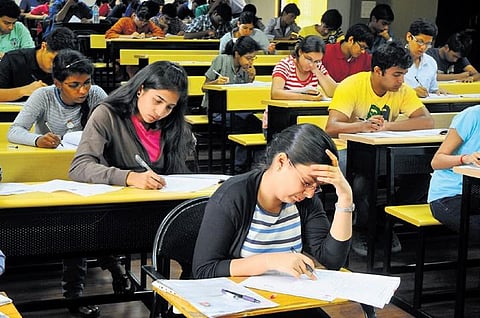

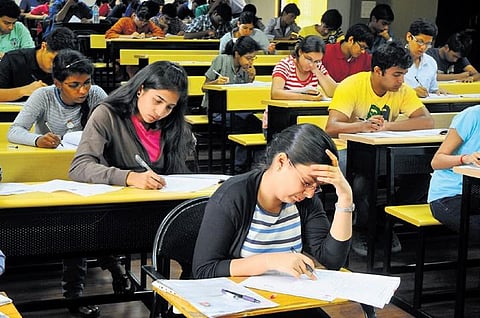

Our education system, coupled with successive governments’ reluctance to revamp it by emphasising on activity-based and experiential learning, has diminished the joy of learning. Even at the tertiary level, the focus remains on rote learning, with three-hour exams still held in high regard. Attempts to reduce exam durations or introduce innovative assessment methods are often met with resistance from traditional educators. The prevailing view of education as merely a means to secure employment and livelihood rather than a pursuit of knowledge has gained prominence. Consequently, parents and teachers exert undue pressure on students to achieve top scores, equating success solely with high marks. Paradoxically, many parents are less concerned about how well their children perform and more focused on why they did not outperform their peers.

Parents bear a significant responsibility in supporting their children and ensuring their well-being, apart from fostering an environment of freedom to make career choices and encouraging them to chart their paths in life. But educational institutions must also undergo a fundamental transformation. Sensitising teachers to students’ problems and teaching them to view students as co-learners is a crucial step. Students may occasionally falter but should not be labelled as delinquents or criminals.

Additionally, talks, training sessions and courses aimed at helping students build adaptive resilience are imperatives. The rhetoric about preparing students to face the world’s myriad problems will be in vain if students do not possess the skills to confront life’s ever-evolving challenges. As a civilised society, we must affirm that education does not manufacture robots but nurtures individuals who can feel, empathise, conceive, and contribute to building a humane world.