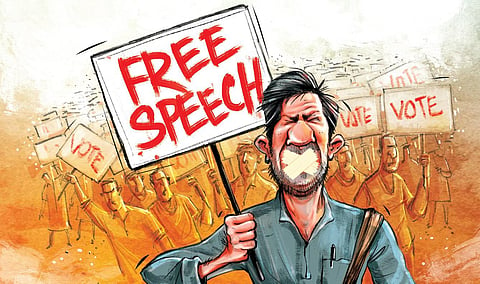

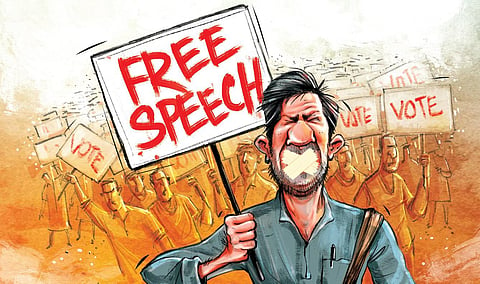

“Never hesitate to speak out boldly against wrongs.” These words of Ramnath Goenka are a perpetual guiding light for Indian journalism. The recent police actions against a few dissenting mediapersons in the capital and elsewhere have further diminished the image of the ruling dispensation, underlining the eternal relevance of Goenka’s words. But speaking the truth is a difficult task, especially during tough times.

Online news portal NewsClick was recently accused by the Delhi police of having a questionable Chinese connection and obtaining illegitimate funding for activities that allegedly challenged the sovereignty and integrity of India. The chief editor and HR head were arrested and charged under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). Raids were conducted on the premises of some senior journalists in various parts of the country. They were reportedly asked about their role in the people’s movement against the Citizenship Amendment Act and the three contentious farm laws of 2020 that now stand repealed.

Many of the allegations in themselves are serious, yet they are vague and obscure. They also lack credibility for want of acceptable materials, at least prima facie. If any illegality is committed by anyone including journalists, he or she should be subjected to the due process of law. If a media outlet acts against national interest, not only the government but the people at large are entitled to know about it, as it is a matter of concern for everyone. But the initial reluctance of the agencies to disclose the allegations or even the First Information Report (FIR) shook the credibility of these agencies, rather than of the journalists. When the FIR ultimately came out, its content only discredited the regime further.

On October 4, a group of journalists’ organisations wrote a letter to the Chief Justice of India. It referred to the CJI’s own views on the duty of the press to speak truth to power. The letter, while expressing the willingness to “co-operate with any bona fide investigation”, said that “sweeping seizures and interrogations” are not acceptable. It also cited cases against Siddique Kappan and Stan Swamy to illustrate instances where the UAPA was blatantly misused.

The UAPA is a draconian law where jail is the rule and bail is not even an exception. According to Section 43D(5) of the Act, if the court feels that the allegations are prima facie true, the accused would not be granted bail. Long incarceration without trial is the hallmark of this law. According to reports, between 2016 and 2020, around 24,134 people were booked under this law. An astonishing 97.5 percent of them are still in prison, awaiting trial.

India’s press freedom rank is 161 among 180 nations. According to the V-Dem Democracy Report of 2023, we rank 108 on the electoral democracy index and 97 on the liberal democracy index. India has been identified as one of ten “quickly autocratising” countries across the world.

The Supreme Court batted for press freedom in the early years of our republic. Ironically, after independence, it protected the left-leaning journal Crossroads in the Romesh Thapar case (1950) and protected the right-wing journal Organiser in the Brij Bhushan case in the same year. We, as a nation, have travelled a lot since then—we have faced the Emergency during which press freedom was blatantly suppressed by the most undemocratic regime after independence, under Indira Gandhi.

The track record of the present regime on freedom of expression is no better than the dispensation that formally proclaimed the Emergency. The regime initially aimed at soft targets such as Disha Ravi and Amulya Leona. Hundreds of civil rights activists, intellectuals and opposition leaders were also booked under various draconian provisions.

In Manohar Lal Sharma vs Union of India (2021), the Supreme Court constituted a committee to probe the allegations in the Pegasus snooping controversy. Though the case has not yielded any ostensible result, the court’s order tried to connect the jurisprudence on the right to privacy, expounded in the famous Puttaswamy verdict (2017), with media freedom. It referred to the foundational English judgement on privacy in Semayne’s case (1604), which stated that every man’s house is his castle. But the journalist’s house, mobile phone and computer devices are so easily seized by the executive with impunity. The top court recently came down heavily on the ban imposed on the Media One television channel in Kerala, citing that the charges were vague and unsubstantiated.

In a pending case before the Supreme Court, Ram Ramaswamy and others vs Union of India, petitioners have sought guidelines for the search and seizure of personal devices such as mobile phones, computers and laptops. The conventional provisions in the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) require a strict interpretation and the scope of these provisions cannot be expanded by removing the safeguards to which a citizen is entitled. For example, under Section 91 of the CrPC, the court can issue summons to produce any specified document. A general search under Section 93(1) of the CrPC is possible only based on a court order. According to Article 20(3) in the Constitution, even an accused cannot be asked to produce self-incriminatory evidence.

All these and many other issues will be germane in the Ram Ramaswamy case, which will necessarily deal with the issue of journalistic freedom in India. The possibility of probe agencies tampering with seized personal devices by implanting materials in them is also a serious concern.

A journal is different from the government’s official gazette. Oppositional radicalism is its lifeblood. Therefore, a journalist requires sufficient legal safeguards to do her job fearlessly. Modern democracies have realised it. In the US, press freedom is a fundamental right. In the UK, journalists are given statutory protection from general search under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act, 1984.

Unless personal liberty is brought to the centre stage of our political discourse and made an electoral issue, it will be difficult for the nation to thrive. In the election after the Emergency, the question of liberty was the major political concern. When history repeats itself, there is a bigger responsibility upon the public.