With two successful moonshots and a Mars orbiter in the bag, a solar probe in flight and a manned mission on the calendar, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is rebranding itself according to changing perceptions about India’s place in the world. The coincidence of an unexpectedly successful G20 summit and a deservedly successful moon landing sharpened that perception. At the same time, it is also sharpening an irony that has dogged India from the time when the first sounding rockets took off from Thumba in Kerala—it’s a spacefaring nation that cannot feed, clothe and educate its people.

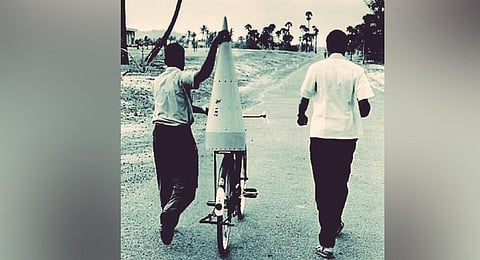

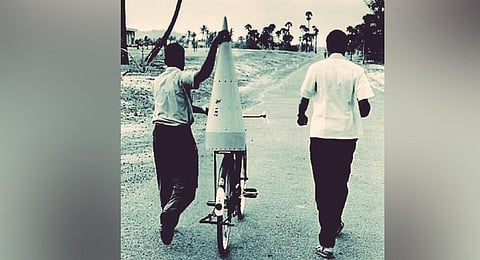

The most compelling pictures of ISRO were shot by Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1966, showing a man wheeling the nose cone of a rocket to the launch pad at Thumba on the carrier of his bicycle. Until the Chandrayaan project began, the Indian space programme was identified with jugaad, and ISRO had defined itself as the world’s cheapest provider of launch vehicle technology. The jugaad tag persists. Mangalyaan was budgeted at $73 million and in the US, National Public Radio marvelled that it was astronomically cheaper than NASA’s $671-million Maven orbiter. It cost less than the Hollywood film Gravity. After Chandrayaan 3 landed safely, ISRO chairman S Somanath laughed off questions about the frugality of the mission, for fear that other space projects would start emulating ISRO’s strategies.

But jugaad may have little to do with ISRO’s economics. The Martian and lunar missions slashed costs by using the angular momentum of the craft in the earth’s gravitational field to sling it towards its target, reducing the need for fuel. This is not jugaad but a completely scientific idea—Arthur C Clarke used it in 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968, a year before Apollo 11 set off for the moon. Apart from that, the cost of inputs, from human resources to rivets, are low in India.

ISRO did not set out to compete with the technologically advanced nations. Vikram Sarabhai was focused on development, not the prestige that moon missions bring—imaging for earth sciences and weather forecasting, and geostationary satellites for running TV stations for national integration. Sarabhai had no idea that anchors yet unborn would polarise viewers and promote national disintegration.

Even now, when the private sector is taking the lead in the US, Indian objectives remain different. Between them, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson are pursuing three goals: tourism at the edge of space, reusable rocket technology for high traffic, and the really big one—preparing for the peopling of the moon and the planets. But in space, as in all else, it is economics rather than science which determines outcomes. Currently, making moons and planets fit for human habitation isn’t commercially viable for both corporates and governments.

In its moon missions, ISRO has focused on a single but crucial component of the big project, which would bring it prestige and establish it as a stakeholder: water. The detection of water on the moon was based on ISRO data, and Chandrayaan-3 has landed in a polar region, where it is more likely to find water ice. A finding would make the region, where other nations have not ventured before, a focus of the search for signs of lunar life. And if water ice is discovered in bulk, it would make it the obvious place to set up lunar bases.

Historically, space missions have served scientific purposes only incidentally. They are packaged as national prestige projects designed to overawe the geopolitical competition and transmit polite threats. Perhaps that was because the development of rocket science and related technologies was spurred by the surge in defence research and innovation during and after World War II. As the nuclear age dawned, détente ensured that technologically capable countries could not go to war with each other any more. They competed by signalling the threat of violence. Space technology is dual use, and during the Cold War, when a nation sent a vehicle into space for the sake of science, it signalled its ability to drop a bomb anywhere on earth. It’s a psychologically compelling message because the weapons platform could be up there anytime, like the Sword of Damocles.

After the first orbiter, Sputnik 1 of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, reached low earth orbit in October 1957, it ran a sound and light show for the whole world for three weeks before its batteries ran out. It was visible as a fast-moving point of light, and it sent out a cheerful beep on the short wave which could be received by home radio sets. It was a cheeky public message to the Americans, letting them know who was ahead in ballistic missile technology. The power inequation was reversed in 1969 by Apollo 11, which decisively put Americans on the moon.

Now, India is doing some geopolitical signalling with its space programme. The US wants it to exert its influence against China’s maritime ambitions. India is technologically and economically far behind China, but it can show off its capabilities in one domain: space. It explains why it is important to put an Indian on the moon—putting boots on the ground is a more compelling signal than sending out drones. Of course, the old irony remains, of a nation which has the wherewithal to put a citizen on the moon but had to screen the slums and tenements of its capital from the disapproving gaze of G20 delegates.

But displacement analysis (how many slums could be improved for the price of a lunar mission) has its limits. India is anyway not going to be a developed nation for decades. It can afford to send a citizen up there right now, and hope that the world gets the message.

Pratik Kanjilal

Editor of The India Cable

(Tweets @pratik_k)