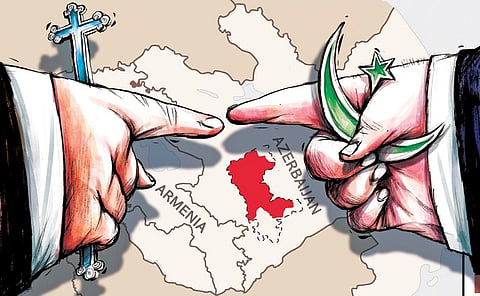

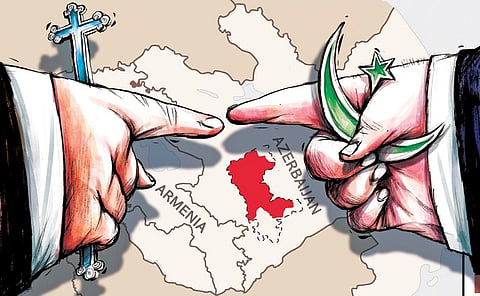

The Caucasus is a rugged expanse of land in eastern Europe between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. It hosts areas of southern Russia and the independent nations of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan—all parts of the erstwhile Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). While geographically this territory lies between Europe, Asia, Russia and the Middle East, culturally it is on the frontiers where Islam meets Christianity; politically, it is the inflection point where imperfect democracy collides with perfect authoritarianism.

Armenia is overwhelmingly Christian, with 97 percent of the population subscribing to the Armenian Apostolic faith, one of the oldest Christian churches founded in the first century CE. On the other side, Azerbaijan is 96 percent Muslim, with 65 percent of the people adhering to Shia Islam and the rest the Sunni faith. Four-fifths of Georgia is Orthodox Christian. The three countries, despite being denominationally disparate, are not avowedly theocratic.

A mirror of this difference can be found in Jerusalem, which is divided into four quarters. The Armenian quarter is the smallest; the others are the Christian, Jewish, and Muslim quarters. A walk through this ancient city brings into sharp relief religious and civilizational conflicts stretching back millenniums.

The reflected faultline in the Caucasus is aflame again with the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Before delving into the conflict and its implications, it is essential to provide a historical context.

For centuries, Nagorno-Karabakh has served as a buffer between three major civilizational strains represented by the Orthodox Christian Russian Empire, the Sunni Ottoman Empire, and the Shiite Iranian Empire. In 1805, the region definitively became part of the Russian empire through the Treaty of Kurekchay. During the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, it attempted to declare independence but was later captured by the Red Army and integrated into the Soviet Union. Within the Soviet structure, the region was included as part of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic with a significant degree of regional autonomy. Following the dissolution of the USSR, Nagorno-Karabakh’s parliament voted in favor of uniting with Armenia. However, this move was not recognized by the newly formed state of Azerbaijan, leading to Armenia’s de facto proxy control over the region.

With the capture of Nagorno-Karabakh by the Azerbaijani military, an independent republic of Artsakh was created in the 1990s. It was given its own government, president, and army flag; but no other country recognized it. This week its President Samvel Shahramayan signed a decree dissolving the State from January 1, 2024. However, this dissolution may be just another tactical halfway house in this civilizational conflict and by no means the endgame.

Armenia’s treaty ally Russia decided to stand down and allow Azerbaijan, a hydrocarbon-rich part of the Caucasus backed by Turkey and Iran, to first blockade and then usurp the region. Now Russia is in no position to burn its bridges with Turkey and Iran, given the bruising it is receiving in Ukraine.

Artsakh survived three decades of war and the pressures of the Great Game in the Caucasus. But its predominantly ethnic Armenian people are now fleeing from the recent onslaught. They are driven by deep-seated fears of ethnic cleansing they had faced in the dying days of the Ottoman empire—the Armenian Genocide of 1916.

From the Armenian perspective, having endured a century of severe persecution and confronted with an omnipresent existential threat from Turkic groups, the preservation of Armenian-controlled Nagorno-Karabakh was an acculturation imperative. Armenians argue that the region has a historical connection to the greater Armenian kingdom. On the other hand, the ethnically Turkic Azerbaijanis harbour deep concerns over the proxy Armenian control over parts of Nagorno-Karabakh that they say lie within its internationally recognized boundaries. They, too, assert historical ties to the region and trace their roots to the Seljuk Empire.

In his thesis, The Clash of Civilizations, Samuel Huntington prophesied that conflicts in the post-Cold War era would be driven by cultural clashes rather than ideological ones. The ongoing conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan is just one among many theatres where such clashes are unfolding. It is for this reason that Turkey, with its Islamic and Turkic affiliations to Azerbaijan, is providing arms and drones that have been used aggressively by the Azeris. Similarly, Armenians, with their cultural and religious ties to Christendom, have historically been supported by the Anglo-Saxon order.

Does the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict have any lessons for India, given that civilizational rather than ideological faultlines would be sharper in the decades ahead?

The Indian civilization is built on a rich tapestry of cultural diversity and pluralism. The intrinsic features of the Indian civilizational construct stand in direct juxtaposition to its neighbors Pakistan and China.

Pakistan, with its acquired Islamic identity and perpetual quest for legitimacy, has drifted very far from the founding vision enunciated by Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who despite authoring a religious partition of India in cahoots with the British, still fantasized that Pakistan could be a pluralistic entity. China, a Sinic civilization with a homogenized demography and an authoritarian state structure, also stands in contrast to India’s multiculturalism.

Also read: Disengagement on the LAC on whose terms

It is therefore existential for India to surmount its major domestic cultural faultlines that could be exploited by its adversaries if it has to deal with its unsettled extrinsic and intrinsic periphery. It is also imperative that it tries to find common ground and develop synergies with like-minded civilizational entities that respect diversity and multiculturalism.

Trying to impose uniformity like ‘one nation, one tax’, ‘one nation, one election’, or ‘one nation, one leader’—worse still, ‘one nation, one megaphone’—would weaken us. India must punch to its civilizational strength of plurality; otherwise, given the monotheism it confronts on its land borders, it runs the risk of becoming another civilizational battlefield.

(Views are personal)

Manish Tewari

Member of parliament, lawyer, and former I&B minister

(manishtewari01@gmail.com)