Innovation propels economic growth by introducing new technologies and processes, transforming industries, and creating jobs, thereby enhancing global competitiveness. Yet, while the value of innovation is universally recognised, actualising it is fraught with challenges, especially in developing countries. Despite the clear understanding that countries and universities should spearhead innovation to foster growth and development, the path is anything but straightforward. Structural issues within organisations and educational institutions often act as formidable barriers.

Innovation transcends the view that it is merely the output of R&D investments with uncertain outcomes. Six inherent difficulties make it difficult for developing nations to build an innovation ecosystem.

First, the synergy between academia and industry is fundamental in driving innovation, blending scholarly research’s theoretical depth with practical insights to push the boundaries of technology and entrepreneurship. The essence of research lies in its unpredictability and foundational role in the innovation process, typically unfolding in academia, where researchers enjoy the liberty to explore diverse avenues without the immediate pressure of market applicability. This freedom is essential for invention and the advancement of knowledge, which, although uncertain in its outcomes, is vital for the stages of applied research and commercialisation.

The division between academic freedom in universities and the goal-oriented research in firms illustrates the symbiotic relationship between basic and applied research, each with its unique role. Challenges in conducting basic research stem from its inherent uncertainty, the need for an open exchange of ideas and the trade-off between freedom and remuneration.

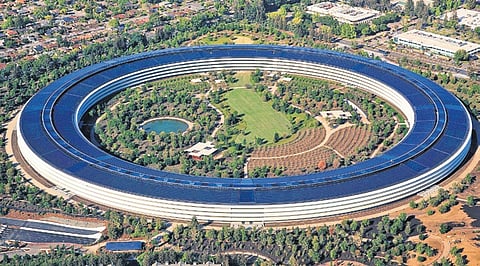

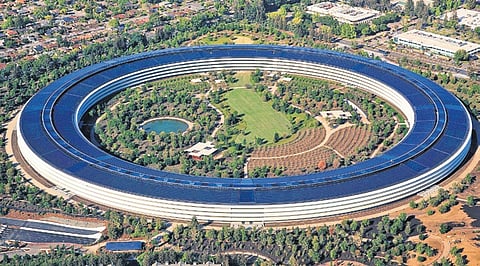

Silicon Valley, where the proximity of high-tech corporations to top-tier universities fosters an environment ripe for technological breakthroughs, is a perfect archetype. Such collaborations have proven crucial in various sectors, notably in pharmaceuticals, where joint efforts have become instrumental in drug advancements.

However, replicating Silicon Valley’s success poses significant challenges for developing nations. They often grapple with inadequate technological facilities, limited access to venture capital, cumbersome regulatory frameworks and a scarcity of skilled professionals. It’s essential for these countries to cultivate environments conducive to innovation, tailored to their circumstances. This includes bolstering STEM education, enhancing infrastructure, streamlining business & R&D regulations, and fostering a culture that embraces innovation and risk-taking.

Second, it is equally difficult to create an environment conducive to innovation. It involves establishing robust legal frameworks, protecting intellectual property rights and fostering a culture of research. These elements are critical for attracting high-calibre talent, yet developing nations struggle with institutional weaknesses and limited resources that undermine this.

Third, innovation ecosystems thrive on networks that facilitate collaboration among local institutions and global knowledge hubs. Developing nations often find it difficult to integrate into such networks.

Fourth, the culture of embracing failure and risk-taking is pivotal as it fosters an environment where creative ideas can flourish without the fear of setbacks.

Fifth, developing nations face substantial challenges in attracting world-class talent and preventing the outflow of their skilled workforce, commonly known as brain drain. Prithviraj Chowdhury’s research at Harvard offers a compelling analysis on this issue. The influx of German and Austrian Jewish scientists into the US during the 1930s, as highlighted by Moser et al (2014), is an example of how skilled migration can catalyse innovation. These migrants significantly increased patenting activity in fields where they were already active, such as chemistry, thereby enhancing the host country’s capabilities.

Sixth, innovation is also a function of the capabilities of the innovator. This is often overlooked when one talks about building an R&D ecosystem. Studies underscore the role of social and familial backgrounds in shaping an individual’s propensity to innovate. The work of Bell et al (2019) and others highlight a stark J-curve between parental income and the likelihood of a child becoming an inventor, revealing a societal stratification in the landscape. For children from lower-income families, the chance of becoming an inventor barely improves with small increases in parental income, hindered by limited educational resources, scarce exposure to innovative settings and fewer networking opportunities. Conversely, as parental income rises, the likelihood of their children innovating escalates significantly, driven by enhanced access to quality education, greater immersion in creativity-nurturing environments, and the financial capacity to overcome innovation-related obstacles.

This relationship is evident not just in the US but also in countries like Finland, suggesting that factors beyond just financial resources critically influence innovative capabilities. Phillipe Aghion, Céline Antonin and Simon Bunel in their book The Power of Creative Destruction have discussed this issue quite comprehensively. They identify three primary social barriers that hinder innovation based on this: financial constraints, knowledge gap, and cultural and aspirational barriers.

Crossing these hurdles is vital for unlocking innovation and driving economic growth. In my next column, I’ll explore perverse incentives promoting low-quality patents in India.

Aditya Sinha

Officer on Special Duty, Research, Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister of India

(Views are personal)