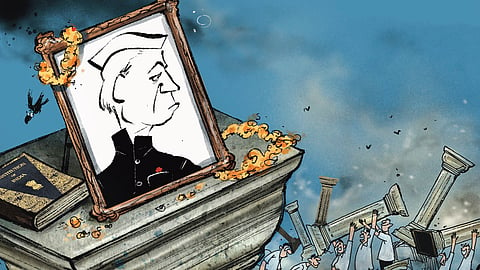

Last month, we celebrated the 75th anniversary of the adoption of our Constitution, less than a fortnight after marking, with considerably less ceremony, the 135th birthday of our first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. The former was, in essence, a celebration of the democracy that our founding Constitution-makers established in an India after centuries of various forms of despotic rule. The latter acknowledged the man who, more than anyone else, ensured that our democracy became much more than a collection of words on a constitutional charter.

Despite the lofty aspirations of the Constitution, it was by no means axiomatic that a country like India, riven by so many internal differences and diversities, beset by acute poverty and torn apart by partition, would be or remain democratic. Many developing countries found themselves turning in the opposite direction soon after independence, arguing that a firm hand was necessary to promote national unity and guide development.

Chaos continued after independence: we were soon at war with Pakistan; refugees continued to flow across the frontiers. Within five months of freedom, the Father of the Nation, Mahatma Gandhi, was assassinated. Two and a half years later, another giant of the freedom struggle and the only one with the stature to challenge the prime minister, his deputy Sardar Patel, passed away.

With these deaths, Nehru could have very well assumed unlimited power. There was no one to challenge his authority had he chosen to misuse it. And yet, he himself was such a convinced democrat, profoundly wary of the risks of autocracy, that at the crest of his rise he authored an anonymous article warning Indians of the dangers of giving dictatorial temptations to Jawaharlal. “He must be checked,” he wrote of himself. “We want no Caesars.” And indeed, his practice when challenged within his own party was to offer his resignation; he usually got his way, but it was hardly the instinct of a Caesar.

As prime minister, Nehru carefully nurtured the country’s infant democratic institutions. He paid deference to the country’s ceremonial presidency and even to its largely otiose vice-presidency; he never let the public forget that these notables outranked him in protocol terms. He wrote regular letters to chief ministers, explaining his policies and seeking their feedback.

He subjected himself and his government to cross-examination in parliament by the small, fractious but undoubtedly talented opposition—allowing them an importance out of all proportion to their numerical strength, because he was convinced that a strong opposition was essential for a healthy democracy. He gave complete freedom to his own backbenchers to challenge him and his government; thus it was that Feroze Gandhi’s relentless attacks on Finance Minister T T Krishnamachari brought about the latter’s resignation.

In contrast with our government today, which has refused to even permit a discussion of the fraught relationship with China in parliament, Nehru allowed parliament to be convened even as the war with China was going on, and took criticism of its conduct from his own partymen as well as the chest-thumping opposition.

Nehru understood the importance of strengthening the fledgling institutions of Indian democracy. He took care not to interfere with the judicial system. On the one occasion that he publicly criticised a judge, he apologised the next day and wrote an abject letter to the chief justice, regretting having slighted the judiciary.

And he never forgot that he derived his authority from the people of India. Not only was he astonishingly accessible for a person in his position, but he started offering a daily darshan at home for an hour each morning to anyone coming in off the street without an appointment, a practice that continued until the dictates of security finally overcame the populism of his successors.

It was Nehru who, by his scrupulous regard for both the form and the substance of democracy, instilled democratic habits in our country. His respect for parliament, his regard for the independence of the judiciary, his courtesy to those of different political convictions, his commitment to free elections, and his deference to institutions over individuals—all left us a precious legacy of freedom.

Nehru’s opening remarks while introducing the objectives at the newly established Constituent Assembly on December 13, 1946 gives us a view of the immense responsibility he placed on himself to ensure that the embodiment of his democratic vision for the country responded fittingly to the situation and did justice to its enshrinement in the process of Constitution-making. He had to preserve the past idea of India and march towards its future idea.

Nehru said, “As I stand here, sir, I feel the weight of all manner of things crowding around me. We are at the end of an era and possibly very soon we shall embark upon a new age; and my mind goes back to the great past of India to the 5,000 years of India’s history, from the very dawn of that history which might be considered almost the dawn of human history, till today. All that past crowds around me and exhilarates me and, at the same time, somewhat oppresses me.

Am I worthy of that past? When I think also of the future, the greater future I hope, standing on this sword’s edge of the present between this mighty past and the mightier future, I tremble a little and feel overwhelmed by this mighty task. We have come here at a strange moment in India’s history. I do not know, but I do feel that there is some magic in this moment of transition from the old to the new, something of that magic which one sees when night turns into day; and even though the day may be a cloudy one, it is day after all, for when the clouds move away we can see the sun later on.”

The American editor Norman Cousins once asked Nehru what he hoped his legacy to India would be. “Four hundred million people capable of governing themselves,” Nehru replied. The numbers have grown, but the very fact that each day 1.4 billion Indians govern themselves in a pluralist democracy is testimony to the deeds and words of this extraordinary man and the visionary giants who accompanied him in the march to freedom.

(Views are personal)

Shashi Tharoor

Fourth-term Lok Sabha MP from Thiruvananthapuram and the Sahitya Akademi winning author of 24 books, most recently Ambedkar: A Life

(office@tharoor.in)