It is that time of the year in Chennai when the city goes Carnatic. The December event, popularly called the Margazhi music season after the Tamil month, is only four years from completing a century. Its creators may not have imagined the shape it would take, as much on YouTube and other online forums as the cherished sabha halls of Chennai.

However, a lot has not changed in the fuddy-duddy Carnatic world, with minds not being broad enough to take in music’s vast horizons. That is what makes for a controversy hotter than sambar poured on piping hot idlis at many sabha canteens.

The real food for thought should be the entrenched habits of Carnatic elitism. Despite all efforts, the season remains a Tamil Brahmin preserve in a land famous for its anti-Brahmin movement.

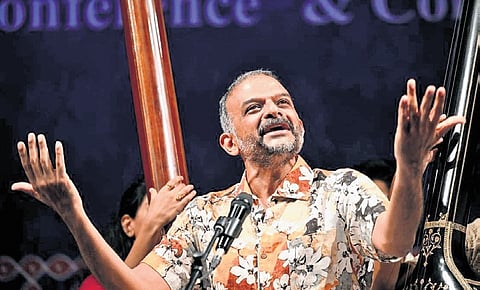

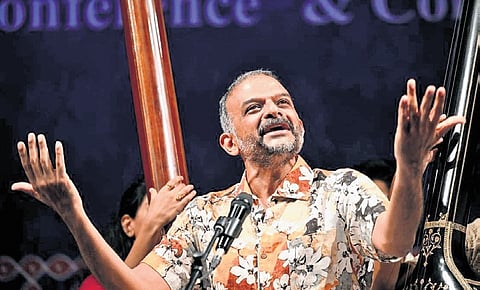

A recent Supreme Court ruling that this year’s recipient of what’s arguably the music’s highest honour, the Sangita Kalanidhi—Thodur Madabusi Krishna—should not be declaring himself an awardee of the honour named after M S Subbulakshmi until an appeal by the legendary singer’s grandson V Shrinivasan is decided, is the latest in a row that smells strongly of entrenched orthodoxy.

Krishna has allegedly besmirched Subbulakshmi’s legacy with his controversial view on how she gained acceptance among the elite Brahmins, and her family’s claim that the late singer had willed no award to be set up in her name.

I had highlighted in an earlier column the class differences between the eminent elite who dominate the Madras Music Academy that awards the Sangita Kalanidhi, and those who aspire to glory from humbler origins.

Krishna is unique in the sense that he has defied his own privileged origins to raise his voice against casteism in his field. He certainly deserves the art’s top honour as he ticks all the boxes: a solid vocalist grounded in rigorous tradition, a music historian to boot and one with a track record that shows excellence in many dimensions. And it was indeed nice to see a glasnost spirit at the Academy when Krishna performed there to a standing ovation this Christmas day after almost a decade.

But what I would like to question are some visible assumptions and conventions in the Carnatic world.

First, we need to ask if the Madras Music Academy should necessarily be the Mecca of Carnatic music. It is a closed private club. Its members just happen to have pioneered a culture of excellence, but need not be the only ones lording over things. There was a time when the Filmfare awards were considered the top honour in Indian cinema. We now have Screen, IIFA and other awards that have shown that many flowers can bloom in an artistic garden.

Then there is my personal view on Subbulakshmi. The late vocalist had an amazing voice, was hugely popular, became the first Indian musician to perform at the UN General Assembly and even received the Bharat Ratna. But connoisseurs with rigorous classical yardsticks may put their money on someone like the late Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, or enjoy comparing female vocalists like M L Vasanthakumari or D K Pattammal with Subbulakshmi—with no one declared a winner. An icon may not necessarily impress nuanced critics in a peer review.

It is also time for Carnatic music to shed its Chennai-centrism. There is a distinct unconscious Tamil Nadu bias that needs affirmative action to get some balance. I have heard excellent musicians from Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka and Kerala and know of local clubs to match, but Chennai remains for the Carnatic world what Lord’s is to cricket.

Born just about two decades ago, the Jaipur Literature Festival is now considered one of the world’s biggest shows of its kind, and has international editions in the US, Canada, Australia and even Spain. Maybe the Carnatic season needs to travel in time and space. The Cleveland Thyagaraja Festival already throws us a hint.

Though the Carnatic world has embraced the violin, the electronic keyboard, the guitar, the piano, the saxophone and the mandolin, Krishna’s attempts to break its social glass ceiling from above have met with quiet but stubborn resistance. There are also allegations of nepotism and unwarranted conservatism in the sabha culture. We need an Alt-Carnatic culture.

I recall an afternoon with L Subramanian, the violinist who took the Carnatic style to jazz and classical fusion, when he ruefully spoke about how he faced resistance from an orthodox set in his own home patch. I have read Subbudu, one of Carnatic music’s respected and controversial critics, writing that composer Thyagaraja should not be made to wear a Western suit. Last year’s Grammy, awarded to Indo-jazz group Shakti enriched over the years by Shankar Mahadevan’s vocals, Vikku Vinayakaram’s ghatam and Zakir Hussain’s tabla, should settle the debate.

It is sad that few speak today of L Shankar, Shakti’s original violinist, whose magic fingers, honed in Carnatic tradition, led to his invention of a two-necked violin playfully named the LSD, or L Shankar’s double-violin. It covers five-and-a-half octaves and takes the cello’s range to a more portable form. His reverse swing is largely unsung.

Much like cricket, whose rulebooks and formats have changed over time, the Carnatic world needs to shed some of its conservatism with some new-age tricks, structures and venues.

(Views are personal)

(On X @madversity)

Madhavan Narayanan | Senior journalist