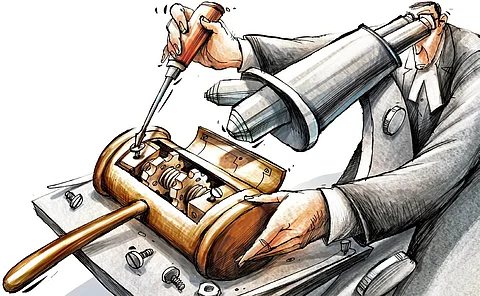

Deleterious intent to disrupt and deceive

The arbitrary, malafide and capricious suspension of 146 members of parliament midwifed into existence, without any informed critique, three draconian criminal laws. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) replaces the Indian Penal Code, Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) substitutes the Criminal Procedure Code (CRPC), and Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) will now stand in for the Indian Evidence Act.

For over a century and a half, thousands of judges from the subordinate judiciary to the Supreme Court have applied the existing laws assisted by over 15 lakh lawyers, a bulk of whom practice on the criminal side. This has created a vast body of criminal jurisprudence. Moreover, the provisions of criminal law such as first information report or FIR, anticipatory bail, police custody, cheating and even murder are well-known to every common citizen even in the remotest part of the country. The new laws are therefore unnecessarily and deleteriously disruptionist in their very conception.

The new laws will be implemented in 17,379 police stations across the country by a police force whose mindset is rooted in coercion and intimidation, governed as they are by the colonial Police Act of 1861.

Out of the 511 provisions in the IPC, only 24 sections have been deleted and 23 added fresh. The rest have been just renumbered in the new BNS. All the 170 sections of the Evidence Act have been retained in the new BSA, just renumbered. Some 95 per cent of the CrPC has been cut, copied and pasted as the new BNSS.

Law is not merely about provisions, it is about substantive interpretation. Each provision of the existing laws—IPC, CrPC and Evidence Act—is settled by judicial pronouncements of courts ranging from the presidency courts, the Privy Council, the various pre- and post-independence high courts, the old Federal Court and its successor, the Supreme Court of India.

The criminal justice machinery is set in motion with the registration of an FIR. A five-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court in 2013 held that FIR registration is mandatory under Section 154 of the CrPC if the information discloses the commission of a cognisable offence and no preliminary inquiry is permissible in such a situation.

Section 173 (3) of the BNSS now makes the registration of an FIR discretionary if the punishment is for an offence where the punishment ranges from 3 to 7 years. One of the debilitating consequences of this new provision, given that power equations are asymmetric, would be that the poor, marginalised, disadvantaged and disempowered sections of society would not be able to get even an FIR automatically registered now.

The second disturbing provision of the new law is Section 187 (3) of the BNSS. The provision is so ambiguously worded that, at first brush, it seems to expand police custody from 15 days to 60-90 days, depending upon the nature of the alleged offence. However, a closer read shows what it does is equally insidious. It allows investigative agencies to seek police custody of an accused for upto a maximum period of 15 days at any time during the total period of custody of 60-90 days, depending upon the nature of the offence.

What this entails is the moment an accused applies for bail during those 60-90 days and even if he clears the triple test for bail, the investigating officer can stymie his or her liberty by asking for police custody for further investigation. The bottom line is that an accused would be mandatorily in police or judicial custody for 60-90 days at least under the new law. This provides a carte blanche for arbitrariness, arbitrage and rent-seeking.

The third controversial provision is Section 43 (3) of the BNSS which brings back handcuffs. In 1979, the Supreme Court in Sunil Batra vs Delhi Administration banned handcuffs, only allowing their use in a minuscule category of cases. This was reiterated by the apex court in the Prem Shankar Shukla case in 1980. The new law expands the power of the police to use handcuffs with little or no restrictions. This again goes against the rulings of the Supreme Court and shall have a pervasive impact on the right to basic human dignity of an accused or an undertrial.

The fourth ominous provision is the rebranding of Section 124-A—the prince among the political sections of the IPC, namely sedition—through Section 152 of the BNS. This new provision criminalises five kinds of activities, namely subversive activities, secession, separatist activity endangering the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India, and armed rebellion. There is, however, no finely-honed legal definition of these terms. It would provide wide latitude to the police and political establishment to persecute anyone without restraint and accountability.

The fifth scandalous provision is that fasting as a form of social and political protest would now be a criminal offence. Clause 226 of the BNS provides, “Whoever attempts to commit suicide with the intent to compel or restrain any public servant from discharging his official duty shall be punished with one-year imprisonment, fine or both, or community service.” Recall that fasting was the non-violent weapon of choice recurrently used by Mahatma Gandhi to overthrow the yoke of British imperialism.

The sixth contentious provision of the new law is the inclusion of terrorism under Section 113 of the BNS. The second iteration of the BNS brings the definition of terrorism in line with Section 15 of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act or UAPA. This results in the creation of two separate laws to deal with the same offence. Moreover, since the UAPA was already created as a special law designed to deal with terrorism, there is no rationale to again reproduce it under BNS, a general law, except that it can now be weaponised as an instrument of intimidation in the pantheon of general criminal laws.

Finally, the new laws add three more capital punishments and six life sentences despite the Law Commission’s recommendations to abolish capital punishment and the Supreme Court’s guidelines to hand down capital punishment in only the ‘rarest of rare cases’. In the previous six years, the Supreme Court has upheld the death penalty in only seven instances.

The list of infirmities in the new laws is endless. A future government or parliament would need to re-examine the very constitutionality and raison d’être of these criminal laws.

Manish Tewari, Member of parliament, lawyer and former Union I&B minister

(Views are personal)