The world is confronted by stark opposites at the start of this year. How we deal with them—dispensing with one, or sewing them together into an unclashing mode of socio-political action—will define our course in the years ahead.

In February 2023, Jorge Heine, one of the three authors of the book Latin American Foreign Policies in the New World Order: The Active Non-Alignment Option, wrote: “Active non-alignment calls on…governments to not accept a priori the positions of any of the Great Powers in conflict. They must act, instead, in defence of their own national interest, without giving in to pressures from hegemonic powers.”

Active non-alignment (ANA) is the successor to non-aligned movement or NAM. ANA is in its infancy—its parameters are still being worked out, a list of characteristics in the process of being drawn up—before it is promoted to the level of a full-blown movement. On its development from a crawl to a movement, it has now halted to map its contours to fall in line with Heine’s definition as “a foreign policy in constant search of opportunities in a changing world, evaluating each of them on their merits”.

Heine’s advice was specifically aimed at Latin America—the so-called “middle class of nations”—in its dealings with the Global North on its stand against Russia in the Russo-Ukrainian war. But, even as every Latin American nation has gone on to disfavour the diplomatic and economic sanctions on Russia pushed by the US and the EU, ANA has become applicable everywhere. In the meanwhile, the Russian war on Ukraine has taken a backseat in the Stromkorridore—the corridors of power—in both the global hemispheres. And a more polarising war has sprung up to take its place—the Israeli genocide in Gaza.

In February 2023, when Heine’s book was published, the UN General Assembly had roundly condemned Russia, calling for its immediate withdrawal from Ukraine: 141 countries for, 32 abstentions, and seven against. The world sided with the Global North, the ANA seemingly quashed.

Ten months later, the very same General Assembly passed a non-binding, symbolic resolution to demand an “immediate humanitarian ceasefire” in Gaza. 153 countries voted in favour of the resolution, 23 abstained, and 10 countries voted against. The ANA had come alive and kicking.

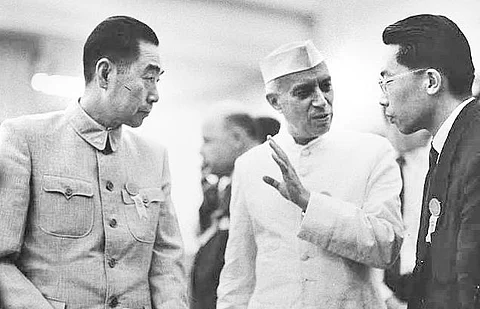

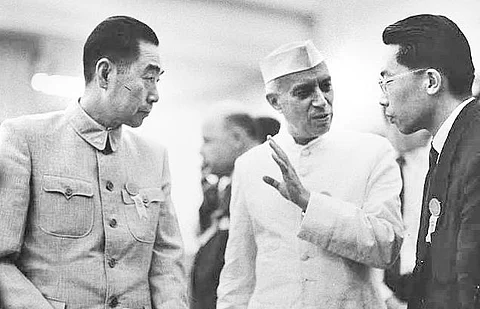

The configuration of the emergent ANA had begun appearing soon after the Western Axis took aim at Russia during its Ukraine misadventure—and India was one of the originators of what, months later, would be acronymed ANA. Narendra Modi helmed it, albeit unaware that he was rolling out a Global South new world order, just as his long-deceased bête noire, Jawaharlal Nehru, had fronted the NAM.

India did so by not only implacably refusing to condemn Russia outright but also, like China, by buying Russian oil embargoed by the Western Axis. India’s argument was unabashedly self-serving: its economy was bettered by cheap Russian oil, the counsel being that while the anti-Russian Axis could weather the economic storm in the wake of a global oil shortfall, India couldn’t, or wouldn’t.

When the West perforce swallowed the insult (for such it was), a new world order was effectively tabled in front of the comity of nations, oppositional to that of the one proposed by George HW Bush in September 1990 during his address before a joint session of Congress, where he said, with the expansiveness of the inordinately privileged, “A hundred generations have searched for this elusive path to peace, while a thousand wars raged across the span of human endeavour. Today that new world is struggling to be born, a world quite different from the one we’ve known. … And one thing more: In the pursuit of these goals America will not be intimidated.”

But America is intimidated, not only by India’s implacability but because of the absolute majority of nations that have seemingly hewed to the call of the ANA. For example, six years after the first NAM conference in Bandung, its summit in Yugoslavia in 1961 was attended by a single Latin American country, Cuba. Today, 26 of the 33 Latin American and Caribbean nations are members.

In January 2023, four Latin American governments—Argentina, Brazil, Chile and, surprisingly, the old American ally, Colombia—coldly passed over a Washington offer to replace their arms inventory with modern weaponry if they donated their old, mouldering arms and ammunition to Ukraine. Some 21 Latin American countries distanced themselves from the Global North, swinging to the other side and becoming part of China’s developing New Silk Road—among them were Argentina, Uruguay, Ecuador, Venezuela, Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, Costa Rica,Cuba and Peru.

“ANA implies but does not necessarily advocate equidistance or neutrality from the major global powers, principally the US and China”, Deepak Bhojwani wrote in an article, ‘Why ANA should be the basis of Latin America’s modern foreign policy’, in April 2023. “It is an attempt at steering foreign policy away from decisions and actions that are not determined by the national interest of the nations which exercise it.”

I would argue that ANA is almost exclusively anti-Western Axis, and, indeed, works in favour of China, which has shown no interest whatsoever in hard-selling its ideology to the rest of the world—much less using force, military or economy, to propagate the virtues of the peculiar political chimaera that runs its body politic. Indeed, it can be ventured that the Chinese government itself is a case of microcosmic ANA, taking from ideology and macroeconomics whatever suits its running of the state.

However, modern-day India is, with typical aloofness of purposality, disdaining of the ANA’s promising paradigm, both in terminology and outlook. In his 2020 book, The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World, S Jaishankar preferred the word “multi-alignment”, with India “seeking strategic convergence rather than tactical convenience”. It seems to me a moment lost, the refusal of a gift of leadership of a momentous—if still not footsure—cause that might redefine international relations for a long time to come.

(kajalrbasu@gmail.com)

Kajal Basu,Veteran journalist