In the just-concluded session of the new parliament, there was one odd historical coincidence and remembrance that created some noise but not enough debate. Om Birla, the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, immediately after he was elected on June 26, moved a resolution condemning the Emergency of 1975. He also led the observation of a two-minute silence, quite unprecedented, and described it as a “dark period” in Indian democracy.

What Birla did was seize the opportunity that June 26 offered—the day Indira Gandhi inaugurated her dictatorial rule in 1975. This was not just an annual reminder, but also marked the beginning of the countdown to the 50 years since the Emergency was proclaimed. Symbolism was written all over Birla’s move. Expectedly, it did not go down well with the Congress.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s words on the occasion unambiguously captured the significance of the act of mourning the historical happening. For him, personally, and for his 10-year-old regime, constantly accused of being authoritarian, it was about turning the tables on the Congress and pulling them down from the moral perch they had come to occupy during the election campaign.

Modi said: “It was also a wonderful gesture to stand in silence in honour of all those who suffered during those days … It is important for today's youth to know about it because it remains a fitting example of what happens when the Constitution is trampled over, public opinion is stifled and institutions are destroyed. The happenings during the Emergency exemplified what a dictatorship looks like.” Obviously, his target was the younger generation, who he suspected to have innocuously walked into frames created by the Congress against him.

The Congress during the poll campaign made the Constitution a political symbol, with an eye mostly on the Dalit and backward class votes. They argued that Modi wouldn’t hesitate to alter the Constitution and its quota guarantees if he was put back on the saddle with huge numbers. Besides, Rahul Gandhi had waved his little red book, a pocket-version of the Constitution, all through the campaign, and also at Modi when he took oath in the Lok Sabha.

On June 26, it was as if Rahul Gandhi was being reminded of his party and his dynasty’s democratic record. Standing up in silence was a powerful act, conceived to perhaps unambiguously register in the minds of younger generations as to when, and what, the real threat to democracy was. It was also perhaps intended to drive home that everything being said about the Modi regime now was mere propaganda, rehearsed to wash off Congress’ guilt from the past, and to deliberately create amnesia about a real event in contemporary history.

What it perhaps meant is that the jibe ‘undeclared Emergency under Modi’ was nothing but a perception manufactured by an old establishment to desperately counter an indelible fact of history. This line became even more apparent in Modi’s two speeches to the parliament during the motion of thanks to the President’s address.

However, the more curious aspect of this contestation is what should have been or be the Congress’ response to this? Should it be angry each time it is raised? Should it continue to draw a feeble equivalence between then and now? Should it be in denial and argue erroneously that the 1975 moment was far benign compared to what has happened since 2014? If it keeps saying this, will it not erode, at some point, the party’s credibility among its own allies, many of whom found political existence during the Emergency on an anti-Congress platform? Will they rewrite their own history?

On the contrary, should the Congress participate in future events that condemn the 1975 Emergency? Should it plainly say that it has learnt lessons from the past and evolved in the last five decades to protect the Constitution? After all, as early as January 1978, addressing a public meeting in Yavatmal in Maharashtra, Indira Gandhi took the “entire responsibility” for all the mistakes and excesses committed during the Emergency. But, she caveated it by saying she did what she did to save the nation.

Similarly, in March 2021, Rahul Gandhi admitted that the Emergency was a mistake but had again qualified it by saying the Congress “at no point had attempted to capture India's institutional framework”. He was wrong there. The Emergency saw the worst corruption and capture of institutions—the ideas of a committed bureaucracy, a committed judiciary, and different forms of ‘chamchagiri’ got entrenched at that point. Money and muscle unabashedly entered politics. It was also a moment in history that birthed the very idea of dynastic rule. Therefore, instead of a half-hearted, caveated admission, instead of presenting it as a reaction to a dire provocation, why not a straight, sincere admission of a mistake and move on?

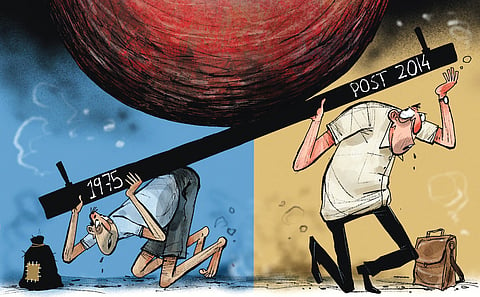

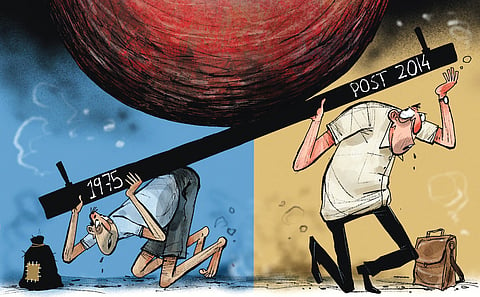

Also, the phraseology of moral equivalence that is often used between 1975 and post-2014 is wrong. Each bend in history is different, if not exclusive. The circumstances, contexts and consequences are all different. Condemn the India under Modi and its democratic deficit by all means, if need be with a stronger formulation. But to present it in relation to the 1975 Emergency is self-defeating.

Noam Chomsky in a BBC interview in 2002, after September 11, put it across brilliantly: “Moral equivalence is a term of propaganda that was invented to try to prevent us from looking at the acts for which we are responsible… There is no such notion. There are many different dimensions and criteria.

For example, there’s no moral equivalence between the bombing of the World Trade Centre and the destruction of Nicaragua or of El Salvador, of Guatemala. The latter were far worse, by any criterion. So there’s no moral equivalence. Furthermore, they were done for different reasons and they were done in different ways. There’s all sorts of dimensions.”

Incidentally, there was another remembrance in June that was forgotten. June 5, the day the poll results were struggling to settle down, was a day 50 years ago in 1974 when Jayaprakash Narayan had given the call for “total revolution”. He had ended his speech in Patna by saying: “When a man loses his head, he thinks there is one man who is causing all the fire. The fire is already there, only you can’t see it.” The Opposition that brought sobriety to our democracy on June 4 had missed this reference in history.

Sugata Srinivasaraju

Senior journalist and author of Strange Burdens: The Politics and Predicaments of Rahul Gandhi

(Views are personal)

(sugata@sugataraju.in)